SCLC Survival Looking Up but Lags Behind NSCLC

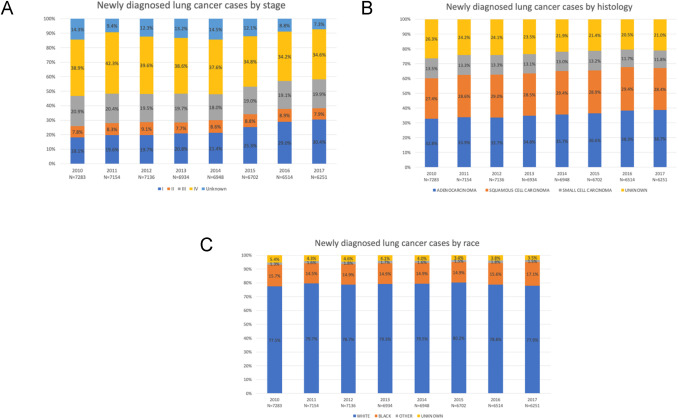

Click to Enlarge: Trends in baseline distributions at diagnosis for (A) stage, (B) histology, and (C) race. Source: Clinical Lung Cancer

LOS ANGELES — Survival rates appear to be somewhat better for veterans and military healthcare beneficiaries diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) but are not as improved as with non-small cell lung cancer (SCLC), according to recent studies.

A key advantage, according to the report in Clinical Lung Cancer, is that both the VA and MHS are universal healthcare systems that provide equal care despite race, ethnicity or ability to pay. So, unlike in the general population, Black veterans are benefiting as much or more than white ones from any increased lung cancer survival rates.1

In addition to equal access healthcare systems in federal medicine, the studies lauded an increase in the percentage of patients diagnosed at earlier stages, improved diagnostic technologies and advancements in medical, surgical and radiation therapies.

Using data from the VA Central Cancer Registry, the study team identified 54,922 veterans with lung cancer diagnosed from 2010-2017. Most of the veterans, 64.2%, had non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with other histologies, including small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (12.9%) and “other” (22.9%).

“The proportion with stage I increased from 18.1% to 30.4%, while stage IV decreased from 38.9% to 34.6% (both p<0.001),” wrote the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System-led researchers. “The 3-year overall survival (OS) improved for stage I (58.6% to 68.4%, p<0.001), stage II (35.5% to 48.4%, p<0.001), stage III (18.7% to 29.4%, p<0.001), and stage IV (3.4% to 7.8%, p<0.001).”

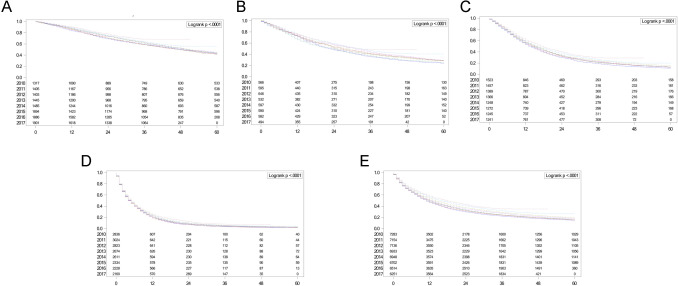

“For NSCLC, the median OS increased from 12 to 21 months (p<0.001), and 3-year OS increased from 24.1% to 38.3% (p<0.001)”, the investigators reported. “For SCLC, the median OS remained unchanged (8 to 9 months, p=0.10), while the 3-year OS increased from 9.1% to 12.3% (p=0.014)”.1

Click to Enlarge: Overall survival rates for combined NSCLC and SCLC analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, stratified by year of diagnosis: (A) stage I, (B) stage II, (C) stage III, (D) stage IV, and (E) stage I-IV. NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer. Source: Clinical Lung Cancer

The authors pointed out that, compared to white veterans, Black veterans with NSCLC had similar OS (p=0.81), and those with SCLC had higher OS (p=0.003). “The observed racial equity in outcomes within a geographically and socioeconomically diverse population warrants further investigation to better understand and replicate this achievement in other healthcare systems,” they added. The VHA is the largest integrated healthcare system in the US and serves approximately 9 million enrollees.

The MHS, which serves approximately 9.6 million beneficiaries through TRICARE, also has reported that its patient population—active-duty servicemembers, National Guard/Reserve members, military retirees and their families—fared better than those receiving civilian care when diagnosed with lung cancer.2

A report in the journal Cancer Causes & Control noted that, in contrast to the MHS and VA, healthcare access varies in the U.S. general civilian population by insurance status/type.

A study team led by researchers from the Murtha Cancer Center Research Program and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, both in Bethesda, MD, divided the patients from the U.S. general population by insurance status/type and compared them to the MHS patients in survival.

The military health system patients were identified from the DoD’s Automated Central Tumor Registry (ACTUR). Patients from the U.S. general population were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. The focus of the study was overall survival.

“Compared to ACTUR patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), SEER patients showed significant worse survival,” the authors pointed out.

The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) were 1.08 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 1.03-1.13], 1.22 (95% CI = 1.16-1.28), 1.40 (95% CI = 1.33-1.47), 1.50 (95% CI = 1.41-1.59), for insured, insured/no specifics, Medicaid and uninsured patients, respectively. “The pattern was consistently observed in subgroup analysis by race, gender, age, or tumor stage,” according to the study. “Results were similar for small cell lung cancer (SCLC), although they were only borderline significant in some subgroups.”

The authors advised that the “survival advantage of patients receiving care from a universal healthcare system over the patients from the general population was not restricted to uninsured or Medicaid as expected, but was present cross all insurance types, including patients with private insurance. Our findings highlight the survival benefits of universal health care system to lung cancer patients.”

Background information recounted how a New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) report in 2020 showed improving survival rates for lung cancer patients in the United States. That study identified increasing 2-year survival rates for men (26%-35%) and women (35%-44%) diagnosed between 2001 and 2014. On the other hand, the rates of lung cancer survival increase were found to accelerate between 2013 and 2016. Unlike in the VHA, “while these increases were observed across different racial and ethnic groups, survival rates remained inferior throughout the study period for non-Hispanic Black men and women demonstrating the persistence of lung cancer racial disparities in the U.S.,” the authors wrote.2

That is in contrast to the findings at the VA, where, according to the more recent study, “Survival rates for veterans with lung cancer who received healthcare through the VHA increased significantly during the study period. This observation was made across all stages and histological subtypes and was coincident with the identification of a 68% relative increase in stage I at diagnosis and an 11% relative decrease in stage IV diagnosis. Further, compared to white Veterans, we observed Black Veterans with NSCLC and SCLC had better or similar survival rates, respectively”

Authors of the NEJM report from the National Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan credited the decreases to the then-recent introduction of recommendations for routine testing of molecular alterations in epidermal growth factor receptor and anaplastic lymphoma kinase, as well as commercial use of related FDA-approved targeted therapies.

The VA authors agreed with that assessment and suggested even more contributors, such as:

- increasing utilization of low-dose chest computed tomography (LDCT) scans for early detection,

- advances in biopsy techniques to increase the likelihood of obtaining a positive biopsy and correctly staging patients at the time of initial diagnosis (e.g., endobronchial ultrasound and robotic bronchoscopy guided systems),

- incorporation of nurse navigators to improve the timeliness of care,

- technological advances improving the safety of lung cancer surgery and radiation therapy delivery systems (e.g., minimally invasive surgery and image guided radiation therapy),

- access to newly FDA-approved targeted therapies and immunotherapies,

- better integration of palliative care for patients with metastatic lung cancer which has been shown to not only prolong survival, but also improve the quality of life for people at the end of their lung cancer journey, and

- decreased wait times for healthcare within VHA since passage of the 2014 Veterans Choice Program.

“Given the complex coordination of healthcare required to successfully work up and manage patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer, further research into the relative contributions of each of these diagnostic and therapeutic factors is necessary to replicate the VHA’s success in other healthcare systems,” they added.

The researchers also noted that the achievement of better or similar survival rates in Black versus white veterans with lung cancer existed in both the VHA and MHS healthcare systems. “Collectively, these findings align with the US Military and VHA’s long-standing culture of ensuring healthcare equity which dates back to Executive Order 9881, written by President Harry S. Truman, which was declared in 1948: ‘There shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.’”

- Moghanaki D, Taylor J, Bryant AK, Vitzthum LK, et. Al.. Lung Cancer Survival Trends in the Veterans Health Administration. Clin Lung Cancer. 2024 Mar 2:S1525-7304(24)00035-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2024.02.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38553325.

- Lin J, Shriver CD, Zhu K. Survival among lung cancer patients: comparison of the U.S. military health system and the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program by health insurance status. Cancer Causes Control. 2024 Jan;35(1):21-31. doi: 10.1007/s10552-023-01765-0. Epub 2023 Aug 2. PMID: 37532916

- Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA, Mariotto AB, Lowy DR, Feuer EJ. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 13;383(7):640-649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623. PMID: 32786189; PMCID: PMC8577315.