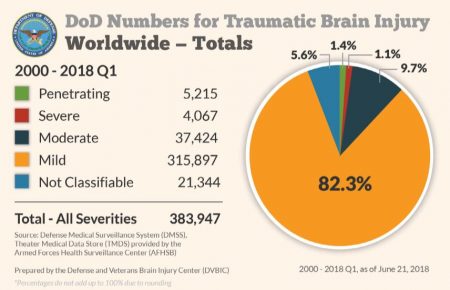

SAN FRANCISCO – Traumatic brain injury has been called the “signature injury” of recent conflicts, with the DoD reporting nearly 384,000 TBIs sustained between 2000 and the first quarter of 2018. More than 4 out of 5 of those TBIs were considered mild, the kind from which most people recover rapidly. But recent research urges continued caution for veterans with any TBI—even mild—as they face an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

SAN FRANCISCO – Traumatic brain injury has been called the “signature injury” of recent conflicts, with the DoD reporting nearly 384,000 TBIs sustained between 2000 and the first quarter of 2018. More than 4 out of 5 of those TBIs were considered mild, the kind from which most people recover rapidly. But recent research urges continued caution for veterans with any TBI—even mild—as they face an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

In a study published in Neurology, researchers at the San Francisco VAMC found that traumatic brain injury of any severity was associated with a 71% increase in risk of Parkinson’s disease. Even mild TBI increased the risk 56%. Veterans with the mildest of TBIs, those that occurred without loss of consciousness, had a 33% increase in risk, though the small number of individuals in this group prevented determination of a significant association.1

While blast-related TBIs affected many military servicemembers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, most TBIs among servicemembers and veterans occur in connection with more ordinary events. Rigorous operational and training activities, motor vehicle accidents, recreational activities and demanding physical fitness programs all increase the risk of TBI in young people. Veterans in their 70s and 80s see the largest increase in TBIs, generally as a result of falls, according to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center.

Protein Aggregation

How does TBI increase the risk of PD? A protein seems to be the culprit.

“Sometimes people who die right after sustaining a very severe TBI have the hallmark protein of Parkinson’s disease and sometimes people develop Parkinson’s disease or Parkinsonism immediately after a TBI,” noted study lead author Raquel Gardner, a staff neurologist at the San Francisco VAMC and assistant professor of neurology at the University of California-San Francisco.

Parkinsonism includes the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, such as slowed movements, rigidity, tremor and poor balance, which may occur in other conditions besides PD.

On autopsy, the brains of people with and without Parkinson’s disease have very different levels of the alpha-synuclein protein. In individuals with the disease, faulty versions of the protein accumulate inside neurons, forming clumps.

“One of the really, extremely exciting things we’ve figured out in the last 10 years is that a lot of age-related disorders—Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—all have abnormal accumulation of proteins in the brain. That’s led to a fundamental shift in our understanding of the brain,” added study co-author Kristine Yaffe, chief of neuropsychiatry at the San Francisco VAMC and vice chair of the UCSF department of psychiatry, neurology and epidemiology.

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by aggregation of misfolded tau proteins, while ALS is characterized by accumulation of multiple proteins. In a fourth disease, Huntington’s, mutant huntingtin proteins form clumps in the neurons of patients.

In all these diseases, the protein massing leads to rupturing of the neuron’s vesicles, which impairs neuronal functioning. The proteins also resist cells’ usual cleansing mechanisms, instead continuing to build up in the brain.2

Previous research indicated that TBI might increase the risk of Alzheimer’s, but other researchers at the San Francisco VAMC determined did not find a link between TBI and increased levels of tau protein, calling that conclusion into question. Instead, they discovered that “people with a history of TBI had much higher levels of alpha-synuclein protein in their brains, even though the injury occurred much earlier in life,” Gardner told U.S. Medicine.3

“That research set the stage,” Yaffe said. “We’re seeing now that TBI may be an important risk exposure for accelerating these proteins developing in Parkinson’s disease. If it takes years before the accumulation has a negative impact on neurons, maybe we have a window of opportunity to intervene.”

TBI Implications

An association between mild TBI and PD could have broad public health implications.

“A handful of studies have tried to estimate lifetime prevalence of TBI in the population,” Gardner said. “About 40% have had some level of TBI in their lifetime, though current studies probably underestimate the lifetime burden in the general and veteran population.”

“All of us had had some sort of fall, sports injury or bump on the head. Even if you don’t lose consciousness, you may actually have had symptoms of TBI, if you didn’t feel well or generally felt out of it,” Yaffe told U.S. Medicine. Other signs of TBI without loss of consciousness include confusion, memory and speech issues, prolonged headache, sensory disturbance, tinnitus, and loss of balance or coordination.

While genetics may play a bigger role than TBI in Parkinson’s disease, it appears to be about as significant as pesticide exposure and other environmental factors, Gardner and Yaffe noted.

To reduce the risk of PD in individuals who have experienced TBI as well as those who have not, Gardner recommended a “brain healthy lifestyle—stay physically, cognitively and socially active and make sure any chronic medical conditions are well managed.”

Individuals who have suffered a TBI need to take an additional step to protect their brains and reduce the risk of PD. “In people who have had TBI, it is extremely important to prevent subsequent brain injury as their risk for having another TBI is higher,” Gardner advised.

Research among athletes indicates that individuals who have had one concussion or mild TBI have three to six times the risk of having a second compared to those who have not had any concussions, according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

For older people, ground level falls are the most common cause of TBI, so it’s important to take steps to reduce the risk of those by eliminating tripping hazards, installing grab bars in the home, using stair railings, increasing lighting, keeping eyeglass prescriptions current, and talking to a healthcare provider about any medications that increase dizziness.

For younger veterans, TBI prevention relies on well-known strategies, Gardner noted: “Drive safely. Wear a seat belt. Use a helmet.”

- Gardner RC, Byers AL, Barnes DE, Li Y, Boscardin J, Yaffe K. Mild TBI and risk of Parkinson disease: A Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium Study. Neurology. 2018 May 15;90(20):e1771-e1779. Epub 2018 Apr 18.

- Flavin WP, Bousset L, Green ZC, Chu Y, Skarpathiotis S, Chaney MJ, Kordower JH, Melki R, Campbell EM. Endocytic vesicle rupture is a conserved mechanism of cellular invasion by amyloid proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 2017 Oct;134(4):629-653. Epub 2017 May 19.

- Weiner MW, Crane PK, Montine TJ, Bennett DA, Veitch DP. Traumatic brain injury may not increase the risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2017;89(18):1923–1925.

On 9.7.98 I was in a car Wreck and was left in a GCS3 coma for 1 month.

I was 16 years old and in High School.

Tons of work and time later I have graduated high school, graduated JC, and am now a Barber. I work for myself and control my schedule just so I can exist. Recovery has been a very long road thus far and will continue for the rest of my life.

Neurofatigue is real!