Isla Garraway, MD, PhD, Greater Los Angeles VAMC investigator, uses a stock photo on her workstation at GLA to demonstrate a prostate MRI. If artificial intelligence research is successful, predictive algorithms will be able to use routinely collected data like MRIs and biopsies to predict how aggressive a case of prostate cancer will be, she explained. VA photo by Claudia Gutierrez.

BETHESDA, MD — The issue of metastasis in prostate cancer can’t really be discussed without a startling fact: Black men are disproportionately affected by prostate cancer (PCa), with earlier presentation, more aggressive disease, and higher mortality rates vs. white men.

The situation is improved in equal access healthcare systems such as the Military Health System (MHS) and the VHA, but the disparities usually aren’t completely erased.

A study last year reported disturbing data related to prostate cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic, finding that Black veterans were much more detrimentally affected than white ones.

“While the late pandemic mPCa rate among white veterans was comparable to the pre‐pandemic rate (5.4 pre‐pandemic vs 5.2 late‐pandemic, p = 0.67), we observed a significant increase in incident mPCa cases among Black veterans in the late pandemic period (8.1 pre‐pandemic vs 11.3 late‐pandemic, p < 0.001),” wrote researchers from the VA Salt Lake City, UT, Healthcare System and colleagues from several other VAMCs. “Further investigation is warranted to fully understand the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the diagnosis of advanced prostate cancer.”

Why did that happen? The study team explained in Cancer Medicine that the absolute declines in PSA testing, prostate biopsy and incident PCa diagnoses were larger among Black veterans compared to those of white veterans. That meant higher‐grade Gleason scores and more incident metastatic disease in Black veterans because of limited access to healthcare, among other reasons.

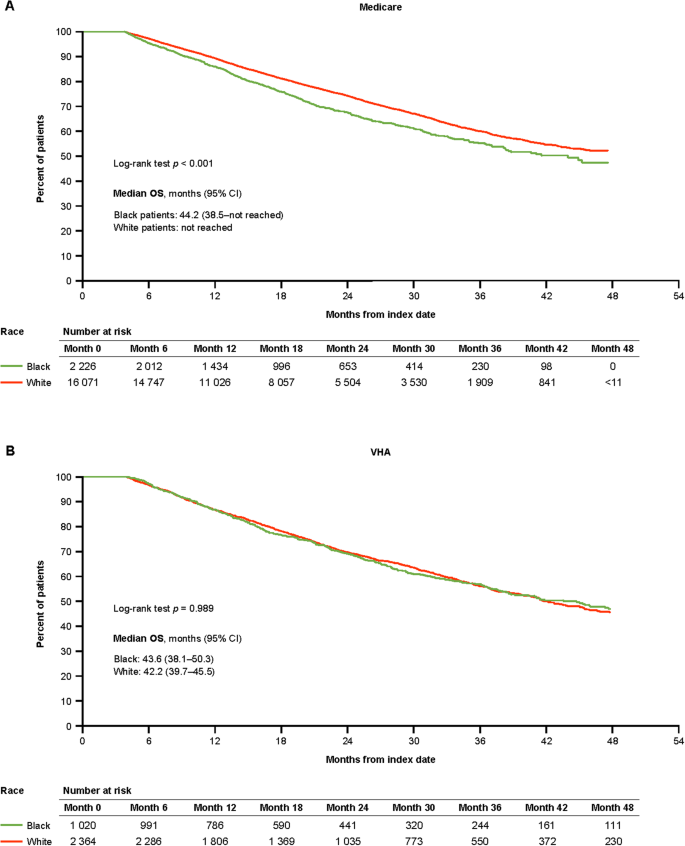

Click to Enlarge: OS among patients with mCSPC by race. Source: Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases

Those disparities didn’t start with the pandemic, however. Some studies have suggested that the increase in later-stage prostate cancer (PCa) at diagnosis occurred after the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended against routine prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer. Past studies have suggested that PCa prostate cancer develops 3 to 9 years earlier in Black men compared with non-Black men.

Black men who fail to have an early diagnosis also fared worse if their metastatic cancer became castration-resistant. A study earlier this year in Nature evaluated treatment intensification (TI) and overall survival (OS) in Medicare (2015–2018) and VHA (2015–2019) patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC).

“Guideline-recommended TI was low for all patients with mCSPC, with less TI in Black patients in both Medicare and the VHA,” wrote the Duke University-led researchers. “Black race was associated with worse OS in Medicare, but not the VHA. Medicaid patients had less TI and worse OS than those without Medicaid, suggesting poverty and race are associated with care and outcomes.”

- Lee KM, Bryant AK, Alba P, Anglin T, Robison B, Rose BS, Lynch JA. Impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of localized and metastatic prostate cancer among White and Black Veterans. Cancer Med. 2023 Feb;12(3):3727-3730. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5151. Epub 2022 Aug 19. PMID: 35984395; PMCID: PMC9538539.

- George DJ, Agarwal N, Ramaswamy K, Klaassen Z, et. Al. Emerging racial disparities among Medicare beneficiaries and Veterans with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024 Apr 2. doi: 10.1038/s41391-024-00815-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38565911.