BETHESDA, MD — Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of lymphoma diagnosed in active-duty servicemembers and veterans. Fortunately, advances in understanding of the disease are leading to more targeted and effective therapies and improved survival rates.

DLBCL accounts for approximately 30% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In the United States, about 25,000 people receive a new diagnosis of this aggressive disease each year and DLBCL is responsible for 5,600 deaths annually.

For decades, the five-year survival rate for DLBCL hovered in the low-40% range, before beginning to rise in the late 1990s, reaching 62% by 2003. This notable improvement resulted from the incorporation of the first targeted therapies into the standard treatment regimens. In the last two decades, the five-year survival rate has risen modestly, and now stands at 64.7%.1

A spate of recent U.S. Food & Drug Administration approvals of new agents, including tafasitamab, axicabtagene ciloleucel, glofitamab, polatuzuma vedotin, and epcortamab could significantly improve those results in the coming years.

As with other cancers, early diagnosis substantially expands treatment options and influences the length of survival. Individuals diagnosed with stage I disease have a nearly 80% five-year survival rate, while those who have stage IV DLBCL at diagnosis have a less than 60% five-year survival rate.

Unfortunately, the often painless and frequently swift progression of the disease results in nearly twice as many people being diagnosed after the disease has spread significantly than when it remains localized. Twenty percent of patients receive their diagnosis at stage I, 19% at stage II, 19% at stage III and 38% at stage IV.

Veterans at Increased Risk

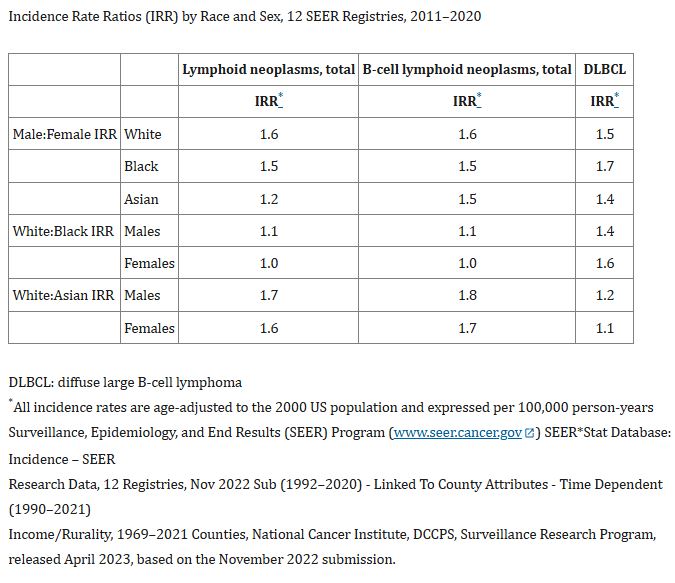

Veterans who receive treatment through the VA have a high rate of risk factors for DLBCL, including older age and male sex. More than three out of four patients are older than age 55 when diagnosed with DLBCL, and more than half are over age 65. In patients younger than age 45, males are two to five times more likely to develop the disease than females, although, across all ages, males are 50% more likely to be diagnosed with DLBCL.2

Chronic infection with hepatitis B, which is more common in veterans than in the general U.S. population, is also associated with an increased risk of DLBCL. Chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection also increases the risk, and while the VA’s aggressive treatment of HCV has made that less of an issue among veterans, the rates are still higher than in the general population.3

In addition, veterans exposed to certain environmental hazards, such as Agent Orange and ionizing radiation, are at an increased risk for developing DLBCL. The VA recognizes DLBCL as a presumptive condition for these veterans.

Other common risk factors include having a first-degree relative who has had DLBCL, chronic immune dysregulation and obesity.

Presentation and Symptoms

DLBCL typically presents as a rapidly enlarging mass, either in lymph nodes or extranodal sites. Common symptoms include painless swelling of lymph nodes in the neck, armpit, or groin. Extranodal symptoms such as abdominal pain or diarrhea, cough or shortness of breath may be initially confused with other common conditions such a gastrointestinal or respiratory infections.

Approximately 30% of patients experience systemic issues known as B symptoms such as unexplained fevers above 103°F (39.5°C), rapid weight loss exceeding more than 10% of body weight in six and drenching night sweats.4

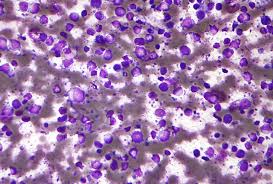

Diagnosis

Diagnosing DLBCL can be challenging due to its heterogeneous presentation and non-specific symptoms. The disease may mimic other lymphomas, reactive lymphadenopathies or inflammatory condition, leading to potential misdiagnosis. A definitive diagnosis requires a comprehensive approach, including histopathological examination, immunophenotyping, and molecular studies. Clinicians are urged to maintain a high index of suspicion when patients present with rapidly enlarging lymph nodes, systemic ‘B symptoms,’ and extranodal involvement.

In addition to clinical evaluation and imaging studies to assess organomegaly and lymphadenopathy, a definitive diagnosis of DLBCL requires an excisional core needle biopsy. Additional immunohistochemistry and genetic studies are typically undertaken to identify specific subtypes of DLBCL, which can influence treatment decisions. Bone marrow biopsy may also be required to confirm limited stage disease.5

Standard Treatments

First-line treatment for most DLBCL cases relies on immunochemotherapy that combines rituximab with cyclosphosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). About 60% of patients achieve remission with this treatment. In certain cases, especially with localized disease, radiation may be used in conjunction with chemotherapy.6

Eventually, about half of patients develop relapsed or refractory DLBCL, however. For these patients, high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation has been considered the standard a second-line therapy for those who can withstand it.7

For those for whom a stem cell transplant is not an option, novel agents including monoclonal antibodies such as tafasitamab and CAR T-cell therapies offer new hope for extended survival.8

- NIH. National Cancer Institute SEER Program. Cancer Stat Facts: NHL—Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL).

- Huang D, Berglund M, Damdimopoulos A, Antonson P, Lindskog C, Enblad G, Amini RM, Okret S. Sex- and Female Age-Dependent Differences in Gene Expression in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma-Possible Estrogen Effects. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Feb 17;15(4):1298.

- Wang SS. Epidemiology and etiology of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2023 Nov;60(5):255-266. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2023.11.004. Epub 2023 Nov 27.

- Mamgain G, Singh PK, Patra P, Naithani M, Nath UK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and new insights into its pathobiology and implication in treatment. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 Aug;11(8):4151-4158. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_2432_21. Epub 2022 Aug 30.

- Chisti MM. B-Cell Lymphoma Workup. Medscape. May 29, 2024.

- Abrisqueta P. New Insights into First-Line Therapy in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Are We Improving Outcomes? J Clin Med. 2024 Mar 27;13(7):1929. doi: 10.3390/jcm13071929.

- Strüßmann T, Marks R, Wäsch R. Relapsed/Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Is There Still a Role for Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in the CAR T-Cell Era? Cancers (Basel). 2024 May 23;16(11):1987.

- Duell J, Westin J. The future of immunotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2025 Jan 15;156(2):251-261. doi: 10.1002/ijc.35156. Epub 2024 Sep 25.