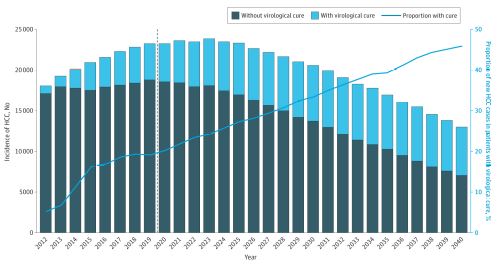

Click to Enlarge: Projection of Annual Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Incidence by Cure Status From 2012 to 2040The dashed line represents the starting year of the universal hepatitis C virus screening in US adults.

LONG BEACH, CA — Hepatocellular carcinoma stands out as one of the few cancers that increased in prevalence over the last decade in the United States. In the VA, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) peaked in 2015 before declining nearly 20% through 2018, but projections indicate that it will regain its upward momentum through 2040.

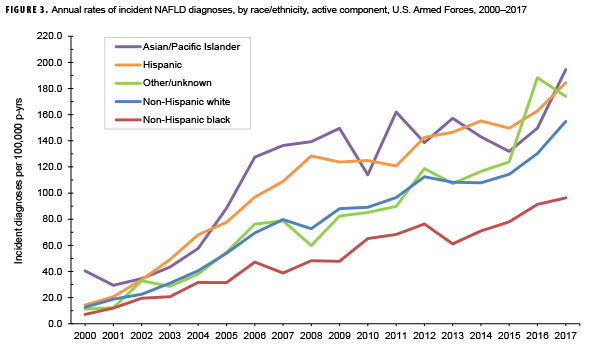

The recent decline and expected rise reflect the intersection of two significant trends. The VA’s aggressive treatment of hepatitis C, until recently the leading cause of HCC, plus wide-spread vaccination for hepatitis B, pushed down the number at risk of developing the malignancy. At the same time, the increasing number of overweight, obese and diabetic veterans continues to pump up the number at risk of developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), now the number one contributor to HCC in the VA. Half of patients with type 2 diabetes have NAFLD, as do 90% of individuals with morbid obesity.

Rising incidence rates for the aggressive cancer are expected to propel liver cancer deaths upward. Liver cancer currently ranks as the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths in the U.S. Over the next 20 years, it is expected to rise to the number three position.1 HCC accounts for 75% to 85% of liver cancers in the U.S.

To combat the rise and identify HCC early, the VA has adapted its advanced liver disease surveillance program, broadening its focus from patients with hepatitis C and cirrhosis to the much larger pool of veterans with NAFLD. In addition, “the VA is developing recommendations for the management of NAFLD and NASH [non-alcoholic steatohepatitis], said Timothy Morgan, MD, director of the VA’s National Hepatitis C Resource Center in Long Beach, Calif., and a professor of medicine at the University of California, Irvine. “We expect the recommendations to be final in the next two months” or so, he told U.S. Medicine.

The disease’s largely silent progression makes finetuning the surveillance program a matter of life and death for many veterans, as timely diagnosis of HCC has a tremendous impact on survival rates. About one-third of patients with HCC receive their diagnosis when the disease is already quite advanced and the window of opportunity for potentially curative surgery has passed. With fewer options, patients with regional spread or metastatic HCC face grim statistics: the combined five-year survival rate is just 5%. Even with early detection, the malignancy remains unusually lethal. The five-year survival rate for those diagnosed with early-stage disease is only 31%.

In addition to saving lives, an effective surveillance program has the potential to save the VA substantial expense. A case-controlled study drawing on data from the VA’s Corporate Data warehouse determined that the average three-year cost of treating HCC was twice the cost of treating similar patients with cirrhosis and six times the average three-year cost for veteran health care.2

Surveillance recommendations and challenges

Current guidelines from both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend semi-annual screening for HCC in all patients with Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) Class A and B cirrhosis, patients with CTP Class C cirrhosis who are on the transplant waiting list, and those with hepatitis B, regardless of cirrhosis status. The preferred screening modality is ultrasound with or without α-fetoprotein (AFP) testing.

The screening recommendations raise several issues. First, “HCC is increasingly being reported in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) without cirrhosis; the pathogenesis of HCC in this population may be different than in the population with viral hepatitis; there are currently no recommendations for surveillance in this population,” the VA notes.

“To further complicate matters, liver ultrasonography, which represents the current standard for HCC surveillance, has a decrease diagnostic accuracy in patients with NAFLD, and therefore disease-specific surveillance tools will be required for the early identification of HCC in this population,” noted researchers at Yale University and the University of Milan.3

Second, the recommendations do not address the diminished, but still significant, risk of HCC in patients treated for hepatitis C who achieved sustained virological response (SVR) but may no longer have cirrhosis. The VA recommends that, in the absence of guidance from professional societies, “patients with stage 3 or 4 fibrosis at the time of initiation of DAA therapy should continue HCC surveillance until more data are available.”

Using histological stage as a predictor of HCC risk, however, is problematic. “Histological stage is not the only predictor of HCC (hence patients with pre-cirrhotic liver disease occasionally develop HCC),” according to George Ioannou, director of hepatology, VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, and professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.4 “This is particularly important after SVR when fibrosis regression may occur but not correlate perfectly with HCC risk reduction because of preneoplastic changes that occurred before SVR.” Further, the clear divisions in histological stage fail to reflect that HCC risk is a continuous variable. With histological stage most commonly determined using non-invasive measures, particularly after SVR, rather than the “gold standard” of biopsy, the process introduces two levels of estimation resulting in calculating HCC risk.

“A better and more accurate approach is to estimate HCC risk directly (rather than indirectly by extrapolating from fibrosis stage) and use this estimate of HCC risk to make decisions about HCC surveillance,” Ioannou wrote. Several tools are available for estimating HCC risk after SVR, including simplified HCC scoring systems (FIB-4), liver elastography, multivariable HCC risk calculators that permit personalization, and deep learning HCC prediction models. Future options may include transcriptomic or molecular profiling.

The VA is working on bringing one of the more sophisticated prediction models to fruition. Ioannou and his colleagues evaluated a recurrent neural network using longitudinal data pulled from electronic health records to determine the HCC risk for 48,151 veterans with hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Using their model, 90% of all patients who developed HCC fell in the mean highest 66% of HCC risk, with even better predictive value for patients who had achieved SVR.

- Rahib L, Wehner MR, Matrisian LM, Nead KT. Estimated Projection of US Cancer Incidence and Death to 2040. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e214708. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4708

- Kaplan DE, Chapko MK, Mehta R, et al; VOCAL Study Group. Healthcare costs related to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma among veterans with cirrhosis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(1):106-114.e105. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.07.024

- Plaz Torres MC, Bodini G, Furnari M, et al. Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Universal or Selective?. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(6):1422. Published 2020 May 31. doi:10.3390/cancers12061422

- Ioannou GN. HCC surveillance after SVR in patients with F3/F4 fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2021 Feb;74(2):458-465. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.10.016. Epub 2020 Dec 7. PMID: 33303216.