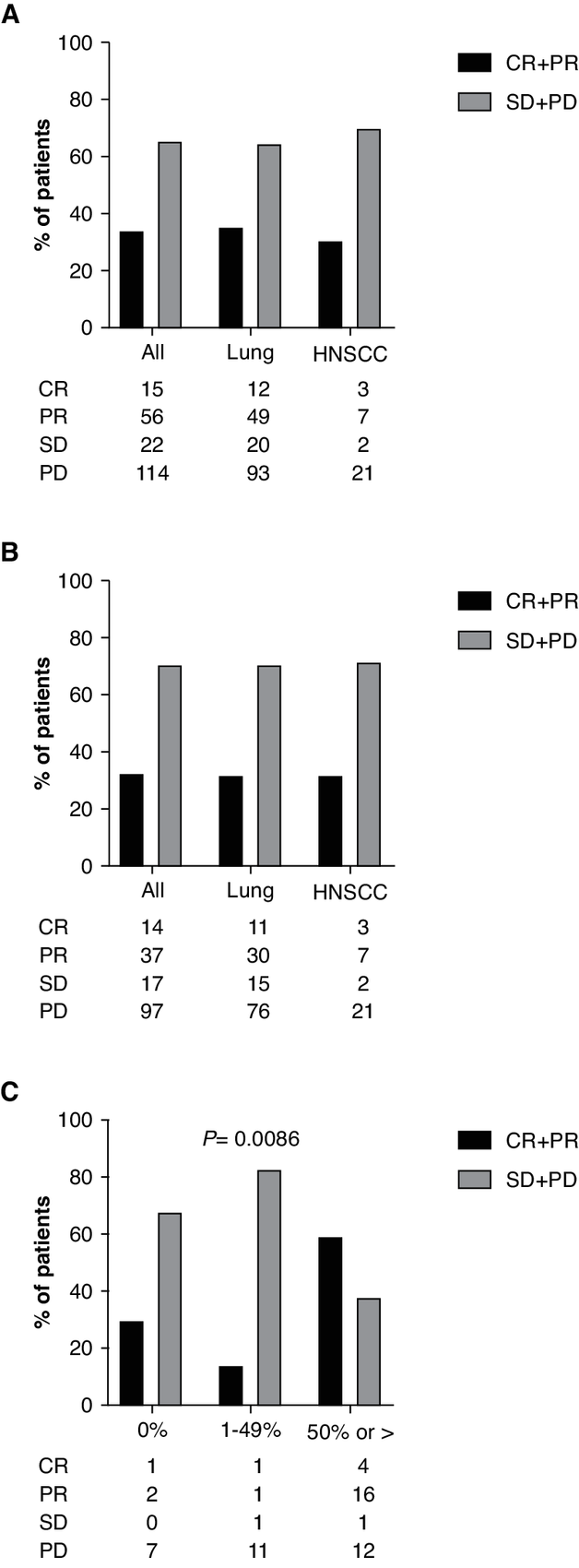

Click to Enlarge: Best overall response. A, ORR data for all patients and by disease category for patients treated with either ICI monotherapy or chemo/ICI combination therapy. B, ORR data for all patients and by disease category for patients treated with ICI monotherapy. C, ORR data for patients with NSCLC stratified by PD-L1 status treated with ICI monotherapy. Only patients for whom PD-L1 was known were included. Source: American Association for Cancer Research

HOUSTON — The Food and Drug Administration approval of the first immune checkpoint inhibitor for non-small lung cancer (NSCLC) changed the course of the disease for many patients and increased survival rates. Despite the success, real world outcomes remain far below what clinical studies would indicate.

Some of the disparity results from the well-known and problematic difference between the relatively healthy populations included in randomized clinical trials and those seen in practice, and some to differences in access to care. VA researchers recently discovered a third significant reason: the drugs elicit very different responses in different ethnic groups.1

A team led by investigators at the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC and Baylor College of Medicine, both in Houston, found that Hispanic patients have much lower objective response rates (ORR) to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) than either Black or non-Hispanic white patients.

Their study analyzed response to ICI therapy in 207 patients treated at the Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, which includes the cancer centers for the Houston VAMC and the Harris Health System, both of which provide care regardless of insurance coverage or financial means. Of the 207 patients treated with chemotherapy/ICI combination therapy or ICI monotherapy between 2015 and 2020, 174 had a diagnosis of non-small cell or small cell lung cancer and 33 had a diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and all had locally recurrent disease for which definitive local therapy was not an option or metastatic disease. Patients self-identified as non-Hispanic white (45%), Black (38%) or Hispanic (18%).

Approximately 20% of the patients in each racial/ethnic group received ICI and chemotherapy together, 20% received ICI monotherapy initially and about 40% received ICI as their first treatment for recurrent or metastatic cancer.

When the team analyzed response to ICIs looking at both PD-L1 status and race/ethnicity, they found that Black and non-Hispanic white patients with PD-L1 of 50% or more had an objective response rate of 65% to ICI monotherapy. Hispanic patients, in contrast, showed only a 29% response rate. In Black and white patients with PD-L1 of 1% to 49%, response dropped to about 20%, while no Hispanic patients demonstrated a response.

In a surprising twist, however, when PD-L1 went to 0%, half of the Hispanic patients showed a partial response, whereas no Black patients and just over 20% of white patients did. That’s particularly notable because ICIs target PD-1, a checkpoint protein on T cells that operates as a switch to control whether T cells attack other cells. It turns the attack off by attaching to PD-L1, a protein on some normal cells. Cancer cells can also have PD-L1, though, and when PD-1 attaches to them, it essentially tells the immune system “these are not the droids you are looking for.” That ICIs would be more effective in Hispanic patients who do not have cancer cells that exhibit PD-L1 than in those who do raises questions about the mechanism of action.

But why?

“This retrospective cohort study identifies a potential signal of decreased ICI-response in Hispanic lung cancer and HNSCC patients,” the researchers wrote. “Coupled with a significantly lower [immunotherapy-related adverse effect] rate for Hispanic patients, the data suggest a possible underlying mechanistic reason for this disparity.”

“Determining which factors may be the cause of this response disparity is one of the most important future goals of this investigation,” co-author Jan O. Kemnade, MD, PhD, assistant professor in hematology and oncology, Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center, Michael E. DeBakey VAMC and Baylor College of Medicine told U.S. Medicine. “Intrinsic causes such as patient genetics/epigenetics could be the cause though such an explanation seems less likely given the large diversity even within the Hispanic population. An extrinsic cause is likely more plausible as patients with similar ethnic/racial background may be exposed to particular toxins, diet, medications etc. which could influence either tumor biology or immunity (or both) leading to decreased efficacy of ICIs.”

Other research has shown that gut microbiome affects ICI efficacy, Kemnade noted, so dietary habits or environmental exposures that influence gut microbiome could be factors.

Implications for Practice

While the findings showed a dramatic difference in response to ICIs in Hispanic patients, Kemnade urged restraint in response. “Even in our cohort, many Hispanic patients saw benefit from ICI therapy and therefore ICIs should continue to be an important treatment tool in all our patients. The Hispanic population is diverse, and making a treatment altering recommendation for the entire population therefore would not make sense. Instead, we need to determine which factors specifically contribute to this disparity and then attempt to influence them to improve ICI response.”

The study reinforced the need to diversify the population included in clinical trials. “In regards to direct clinical practice, our study should have no influence on current treatment algorithms,” Kemnade said. “However, our results clearly highlight a glaring gap in our available prospective ICI clinical trial data: minority patient representation.” More than 70% of the participants in the clinical trials that led to the approval of ICIs for NSCLC were white; in several key trials, white patients made up 90% or more of the participants.

“We state in our discussion and believe strongly that a concerted attempt is needed to dedicate effort and resources toward providing minority patients with the opportunity to enroll in ICI clinical trials.”

- Florez MA, Kemnade JO, Chen N, Du W, Sabichi AL, Wang DY, Huang Q, Miller-Chism CN, Jotwani A, Chen AC, Hernandez D, Sandulache VC. Persistent ethnicity-associated disparity in anti-tumor effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors despite equal access. Cancer Res Commun. 2022 Jul 26;2022:10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-21-0143.