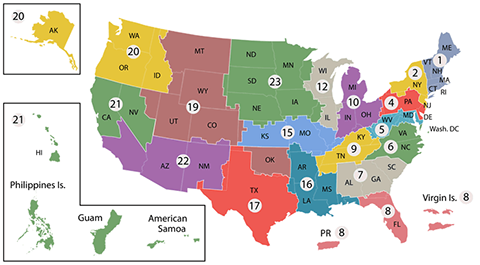

Click to Enlarge: Regional Procurement Offices (RPOs). The RPOs are subdivided into Network Contracting Offices (NCO). The NCO’s share the same identifying number as the Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISN) they are located in. Each NCO provides local, regional, and national procurement support toward providing the best possible care and support to our Veterans.

WASHINGTON, DC — Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are upset at VA for delays in providing Congress with information about its ongoing Supply Chain Modernization (SCM) project. Meanwhile, department officials are defending their actions, saying there’s not enough information to report and that the modularization of the project might result in individual elements falling below the $1 billion mandatory reporting cap.

This has some legislators questioning whether VA designed the project this way to avoid congressional reporting requirements, adding more controversy to another major IT endeavor that has already dragged longer than VA or Congress had anticipated. Gaps in the department’s purchasing, inventory and supply-chain systems were brought into high relief during the pandemic, when shortages in medical supplies left many facilities scrambling and VA unable to track national inventory.

“The [SCM] project is a gigantic effort the likes of which we have only seen in the EHR, and we know how that’s turned out,” said Rep. Matt Rosendale (R-MT) at a hearing of the House VA Technology Modernization Oversight Subcommittee. “The VA has been soliciting proposals from contractors to do this for nearly a year, and we’re now hearing a contractor award is imminent. The life-cycle cost estimate is stratospheric, and there does not seem to be any approved budget. The effort may extend for a decade, but there’s no schedule. I’m concerned, in effect, that the government will be paying a contractor in order to find out what the government will be buying from that company.”

A day ahead of the hearing, VA provided the subcommittee with over 200 pages of documents, Rosendale said, including the estimated life-cycle cost of between $9 billion and $15 billion. Recently enacted IT reporting regulations require the department to deliver estimated cost, schedule, and performance metrics before beginning any project over $1 billion.

“The $9 billion to $15 billion is an initial estimate,” explained VA’s Chief Acquisition Officer Michael Parrish. “It’s working on assumptions that have been found to be incorrect. That is not a valid budget to be able to commit to yet with VA.”

The initial estimate, he explained, accounted for billions in new hardware that will not be necessary under this contract.

Asked how VA could possibly expect to shave a minimum of $8 billion off the contract costs, thereby justifying their delay in reporting project details to Congress, Parrish said the SCM is not one single project but many smaller ones overseen by a single contractor. It’s a lesson, he said, the department learned after committing to the Cerner-Oracle EHR.

“[Congress has been] concerned that this is too big of an effort, so what we’re doing is modularizing it,” Parrish explained. “Think of subcomponents—each one of those are separate technology solutions.”

“We’re not committing to a singular technology,” he added later. “We’re coming to a service [company] that can find those technologies. It’s not a silver bullet. It’s 7 to 10 different technologies.”

He also noted that the project will happen in phases, the first of which is a validation phase that will require whatever company is awarded the contract to submit a proposal for how to move forward. Only after that proposal is accepted will VA have a firmer idea of budget and scheduling.

That explanation did little to assuage the committee members.

“The letter of this law is meant to be a transparent conversation between Congress and the VA, and that isn’t being met,” said Rep. Cherfilus-McCormick (D-FL). “With everything you’ve submitted to us, it has met that [$1 billion] threshold.”

VA officials have testified that the department’s supply chain needs are incredibly complex, existing of multiple separate inventory chains working together–the main reason the project can be modularized. It also makes a single, off-the-shelf solution unlikely, if not impossible.

This is what VA attempted in 2019 when it deployed DoD’s Defense Medical Logistics Standard Support (DMLSS) system, which was expected to cost $2 billion over a 15-year deployment. When the system was piloted at the James A. Lovell Federal Healthcare Center in Chicago, it failed to meet 40% of VA’s needs. VA decided three years later to scrap it.

This failure, along with others of its kind, resulted in the Congressional IT project reporting reforms that lawmakers are accusing VA officials of skirting.