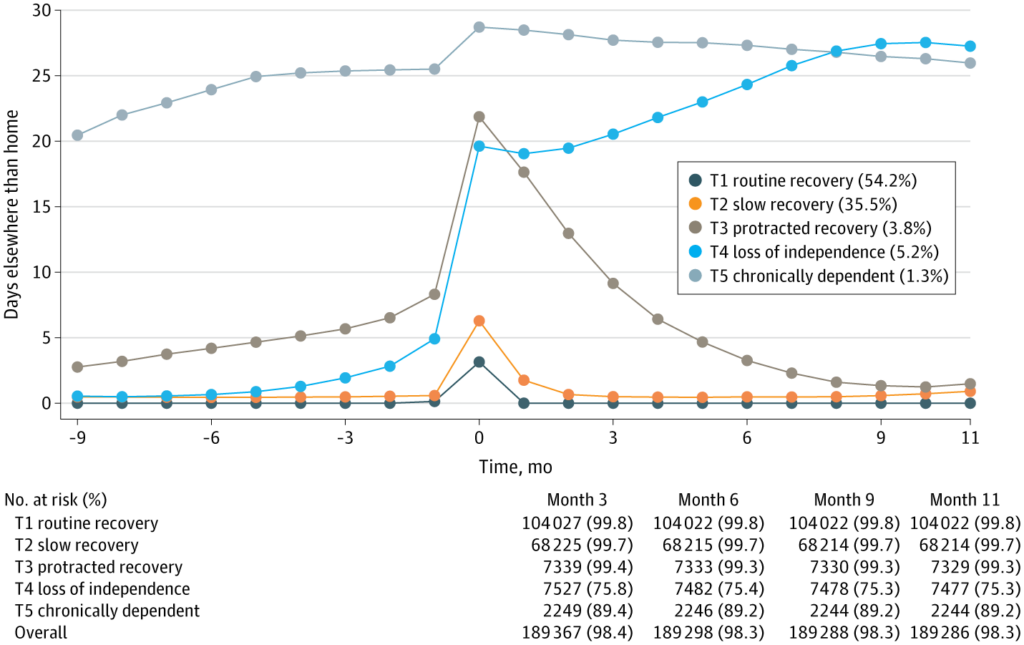

Click to Enlarge: Trajectories of Days Elsewhere Than Home in Older (65 Years and Older) VeteransEach point represents a 30-day period. Time 0 is the 30-day period of surgery (with the day of surgery being day 6 in month 0); negative time represents presurgery and positive numbers postsurgery. Period averages are visualized by trajectory group, rather than smooth quadratic curves. The 5 trajectories are: (1) routine recovery with minimal, if any, inpatient health care before and after surgery with a peak during the month of surgery; (2) slow recovery with a slightly higher baseline of inpatient health care, and required a month after surgery to return to its relatively independent baseline; (3) protracted recovery with increasing inpatient health care leading up to surgery with each month averaging around 5 days in some inpatient setting and took approximately 4 to 6 months to return to an elevated, slightly dependent baseline which was lower than prior to the surgical procedure; (4) loss of independence which never returned to baseline—these patients may have been permanently institutionalized or died in a dependent health care state; and (5) chronically dependent with large amounts of inpatient care before and after surgery. The loss of independence and protracted recovery trajectory lines crossed in between the month of surgery and first postoperative month. T1 indicates trajectory 1; T2, trajectory 2; T3, trajectory 3; T4, trajectory 4; T5, trajectory 5. Source: JAMA Network

PITTSBURGH — Surgical outcome studies often focus on mortality, complications or hospital readmissions. While such outcomes are important, they don’t always align with matters most to older patients, particularly those nearing the end of life.

That’s according to Daniel Hall, MD, a staff surgeon at VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and the co-author of new study whose findings support “more patient-centered discussions between surgeons and patients, especially on issues critical to veterans’ quality of life, like maintaining independence.”

“From our clinical experience, we knew that surgery sometimes marks the transition from independence to dependence on family or long-term care,” Hall told U.S. Medicine. “However, this transition hadn’t been measured at a population level, which is what we aimed to address.”

To document, on a national scale, a significant challenge some patients face as they recover from surgery, Hall and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (SQIP) data linked to a Residential History File. Results were published in JAMA Surgery.1

SQIP is a VA-developed initiative that was later adopted by the private sector and embraced by the American College of Surgeons. Nurses systematically sample surgeries within a hospital system, collecting patient and care data from preoperative to postoperative stages, he explained. “This data enables quarterly performance comparisons across hospitals, which has significantly reduced postoperative mortality over the past 30 years. However, SQIP was previously limited to outcomes within 30 days of surgery.”

By linking SQIP data to the Residential History File—which combines long-term datasets from Medicare, Medicaid, nursing homes and other sources—the researchers were able to overcome this limitation.

“This extended timeline let us assess recovery and healthcare use over an entire year,” said Hall, who is also a VA Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion (CHERP) core investigator. “What that means is that for a systematic sample of all surgeries in the VA, we had a reliable indicator of each person’s healthcare use inside and outside the VA for each day of the year before and after surgery.” This allowed the researchers to analyze recovery paths and identify loss of independence at an unprecedented level of detail.

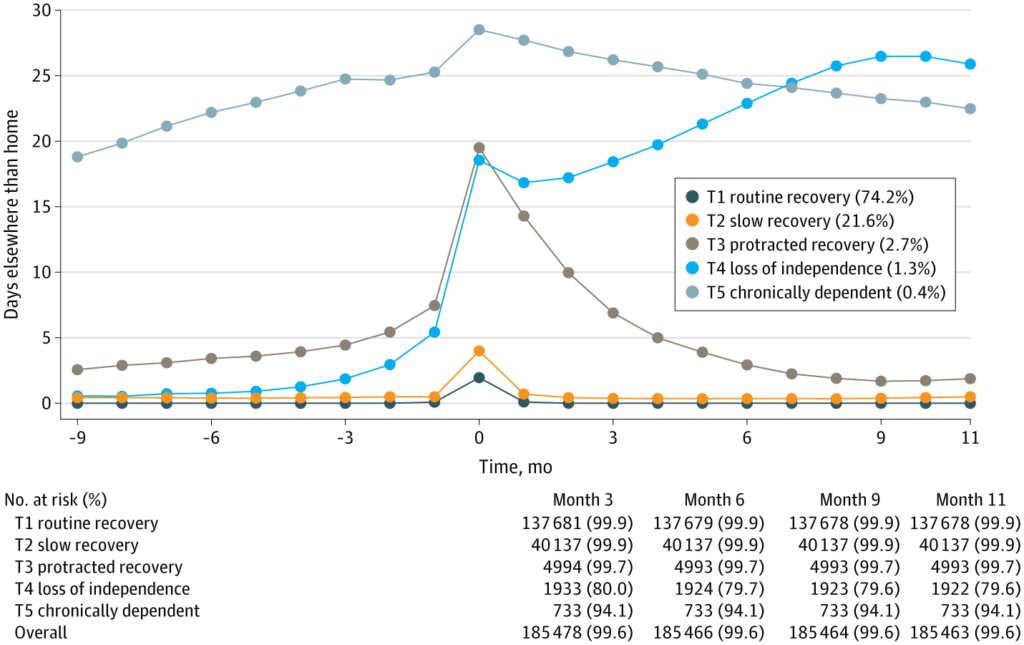

The cohort of 378,682 surgical patients was divided into younger (younger than 65 years) or older (65 years or older) subgroups, as Medicare eligibility is age dependent. Five postoperative recovery trajectories—routine, slow and protracted recoveries, loss of independence and chronic dependence—were developed and included in the study. Days elsewhere than home (DEH) were counted in 30-day periods for 275 days presurgery and 365 days postsurgery.

“As expected, most patients recovered well within one to two months after surgery,” Hall said. Seventy percent of younger patients and 54.2 % of older patients returned home within 30 days; 21.6% of younger and 35.5% of older patients described delayed recovery within 30 to 60 days.

However, the researchers also identified two smaller groups: one group that never regained independence and another group with prolonged recovery, taking nine to 12 months, which was unexpected, Hall said.

Click to Enlarge: Trajectories of Days Elsewhere Than Home in Younger (Younger Than 65 Years) VeteransEach point represents a 30-day period. Time 0 is the 30-day period of surgery (with the day of surgery being day 6 in month 0); negative time represents presurgery and positive numbers postsurgery. Period averages are visualized by trajectory group, rather than smooth quadratic curves. The 5 trajectories are: (1) routine recovery with minimal, if any, inpatient health care before and after surgery with a peak during the month of surgery; (2) slow recovery with a slightly higher baseline of inpatient health care, and required a month after surgery to return to its relatively independent baseline; (3) protracted recovery with increasing inpatient health care leading up to surgery with each month averaging around 5 days in some inpatient setting and took approximately 4 to 6 months to return to an elevated, slightly dependent baseline which was lower than prior to the surgical procedure; (4) loss of independence which never returned to baseline—these patients may have been permanently institutionalized or died in a dependent health care state; and (5) chronically dependent with large amounts of inpatient care before and after surgery. The loss of independence and protracted recovery trajectory lines crossed in between the month of surgery and first postoperative month. T1 indicates trajectory 1; T2, trajectory 2; T3, trajectory 3; T4, trajectory 4; T5, trajectory 5. Source: JAMA Network

“We anticipated finding a group that lost independence, but the extended recovery period surprised us. This pattern couldn’t be detected in the first 30 days after surgery, as it only became evident through long-term data from the Residential History File. These insights can now guide patient discussions, helping set realistic expectations, including the possibility of a yearlong recovery or potential loss of independence,” he said.

“The possibility of this adverse outcome is critical information for shared decision-making in elective, urgent, and emergent contexts because many patients, especially those with limited life span, prefer less or no treatment when treatment is associated with high functional or cognitive impairment risks,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Surgery. For example, in one previous study, “99% of seriously ill patients 60 years or older stated they would agree to routine treatment that was likely to restore health,” the wrote. “However, 74% to 94% of these patients reported that they would forgo such treatments if there were a significant chance of functional or cognitive impairment, accepting a shortened life span to preserve quality of life.”

“Our findings can be used by surgeons and referring clinicians as they consider surgical treatment,” Hall said. They will help set realistic expectations for outcomes and inform a more robust process of shared decision-making to ensure that the treatments provided are aligned with patient’s goals and values, especially regarding independence and quality of life.

“The VA has achieved strong surgical outcomes, which are often as good or better than those in the private sector,” he continued. “Because challenges to full recovery still exist for most patients, though, our study helps paint a picture of what long term postoperative recovery can look like. Armed with this data, patients and surgeons can form more realistic expectations to determine if surgery aligns with the patient’s personal priorities, particularly if they highly value independence.”

- Jacobs MA, Jacobs CA, Intrator O, Makineni R, Youk A, Boudreaux-Kelly MY, McCoy JL, Kinosian B, Shireman PK, Hall DE. Long-Term Trajectories of Postoperative Recovery in Younger and Older Veterans. JAMA Surg. 2024 Oct 23:e244691. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.4691. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39441611; PMCID: PMC11500012.