Potential to Fix Two Huge Problems with the U.S. Healthcare System

CAMBRIDGE, MA—Rising drug prices have frustrated patients nationwide, often leading individuals to forgo needed therapies because they simply could not afford them. In some instances, cost-control measures have kept life-saving medications off plan formularies or relegated them to high tiers with copays that run into the thousands of dollars for a course of treatment.

States and the federal government have pursued multiple avenues to control prices. In 2019, 37 states passed 60 separate drug-pricing laws, according to the American Medical Association. Both houses of Congress passed bills to reduce the price of prescription drugs last year, too, though not the same one, and the president called for Congress to send him legislation addressing the issue that he could sign into law in his State of the Union address.

A study in Health Affairs suggests that legislative efforts to create a new model for prescription drug coverage that lowers the national burden associated with high drug costs and enables more patients to obtain the medication they need have overlooked a system that already achieves these goals. The authors pointed out that the system exists at the VA.1

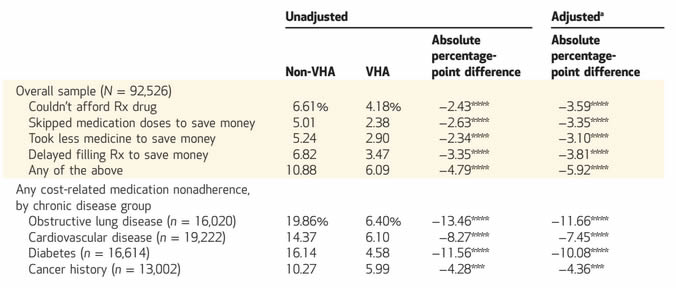

Cost-related medication nonadherence among people with Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and non-VHA coverage, 2013–17

SOURCE Authors’ analyses of data for 2013–17 from the National Health Interview Survey. NOTES Chronic diseases are explained in the text. Adjusted models are linear probability regressions adjusted for age, sex, income (continuous), race/ethnicity, marital status, family size, health status, obstructive lung disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer history, employment status, and coverage status (VHA versus non-VHA coverage). For adjusted analyses, numbers of people were 91,850 for the overall sample, 15,929 for obstructive lung disease, 19,066 for cardiovascular disease, 16,481 for diabetes, and 12,910 for cancer history. ***p < 0:01 ****p < 0:001

“While people often look abroad for lessons on how to reform the American healthcare system, there are many things we can learn from within our borders,” said lead author Adam Gaffney, MD, MPH, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School and Cambridge Health Alliance.

“The VHA does an excellent job purchasing drugs affordably, and making them available to veterans at low out-of-pocket cost. We should consider it a model for reform,” he told U.S. Medicine.

Keeping the costs down for patients translates directly into greater adherence to recommended therapies and improves patient outcomes, leading to lower overall healthcare costs as well as improved quality of life and reduced mortality from treatable conditions, the authors said.

Specifically, the study found that veterans who received care through the VA were much less likely to forgo or delay filling prescriptions or skip doses because they could not afford the medications than patients with other types of insurance. It also found that VA coverage largely eliminated racial and economic disparities in prescription drug access.

Cost Issues

The researchers compared 2,556 veterans with VHA coverage to 89,970 individuals with other insurance. Participants were asked whether they had “needed … [a prescription drug], but didn’t get it because [they] couldn’t afford it”; “skipped medication doses to save money”; “took less medicine to save money” or “delayed filling a prescription to save money.” The team used a composite outcome that indicated any cost-related medication nonadherence in its analysis.

On average, the veterans were older, had higher rates of chronic disease and were more likely to be male, black and of lower income.

While 6.1% of veterans said that costs kept them from taking their medications as prescribed, the rate among patients with other insurance was more than 50% higher at 10.9%. On a fully adjusted basis, the difference was 5.9%.

For patients with chronic disease, the rates were even more striking. Among those with non-VHA coverage, 1 in 5 patients with obstructive lung disease reported cost-related medication nonadherence compared to 1 in 16 veterans. Among individuals with cardiovascular disease, 14.37% of those with non-VHA coverage reported affordability issues that led to non-adherence versus 6.1% of veterans. For those with diabetes, costs led to nonadherence for 16.14% of patients with non-VHA coverage but only 4.58% of veterans. The difference was somewhat smaller for patients with a history of cancer, 10.27% vs. 5.99%, for non-VHA and VHA coverage, respectively.

Less than 9% of veterans in the lowest socioeconomic tier —defined as an income of $0 to $34,999 —reported nonadherence for financial reasons, almost half the rate seen in those of the same economic position who had other types of insurance at 17.25%.

“High copays and deductibles are forcing patients to skip their medications—even for serious illnesses like heart disease or lung disease—putting their health, and even their life at risk. The VA shows that there is a better way,” said senior author Danny McCormick, MD, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a primary care physician.

Impact on Health

The impact extends well beyond the four conditions analyzed in the study.

“Multiple studies and common sense suggest that out-of-pocket costs worsen outcomes,” said Gaffney. “Recent studies, for instance, have found that out-of-pocket medication costs worsen blood pressure because of nonadherence and cause people with multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis to go without the drugs that control their illnesses. Another study published last year found that women with high-deductibles and breast cancer delay diagnostic tests and even chemotherapy.”

Veterans pay a maximum of $11 for a prescription. In contrast, patients who require specialty drugs such as chemotherapy for cancer or biologics for autoimmune disorders might pay thousands of dollars in copays under many other types of insurance. Medicare patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease would pay $1,600 per year for inhalers, the authors noted, compared to an annual maximum of $132 for veterans.

Hepatitis C treatment under Medicare Part D would cost older adults about $5,000, while treatment within the VA would run $33. Patients on many private insurance plans could not get hepatitis C therapies at any cost. More than half of patients prescribed the direct-acting antivirals receive “absolute denials” from private insurers, despite their demonstrated ability to eliminate hepatitis C in more than 95% of patients in three months and to sharply reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, liver failure and other complications.

Negotiated Pricing

Some of the restrictions imposed by private plans aim to reduce the rising cost of pharmaceuticals for the plans and their members. Gaffney and his colleagues recommended following the VA’s example here as well.

“It would be difficult to implement a VHA-like pharmacy benefit for the whole nation, given our fractured system,” Gaffney said. “However, we could do it for patients with Medicare. Additionally, if we passed a Medicare for All system, a VHA-like pharmacy benefit could be made available for the whole nation.”

More modestly, the authors found that adopting a VA-like program that enables Medicare to negotiate prices with pharmaceutical companies and use a national formulary, even one with access permitted on a case-by-case basis like the VA’s, would reduce overall healthcare costs for the nation while improving access for patients.

“What we know is that far too many Americans are skimping on their medications or not taking them altogether, because they cannot afford them—which is a terrible travesty,” Gaffney said.

“Today, we have better drugs—more ways to help our patients—than ever before,” he noted. “But these drugs offer no help to patients who can’t afford to take them. By reforming how we pay for prescription medications, we can improve health outcomes, while bringing our drug spending in line with that of other rich nations.”

- Gaffney A, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, McCormick D. The Effect of Veterans Health Administration Coverage on Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence. Health Affairs. January 2020;39(1):33-40. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00481