Appropriate COVID-19 Treatment Might Have Been Delayed

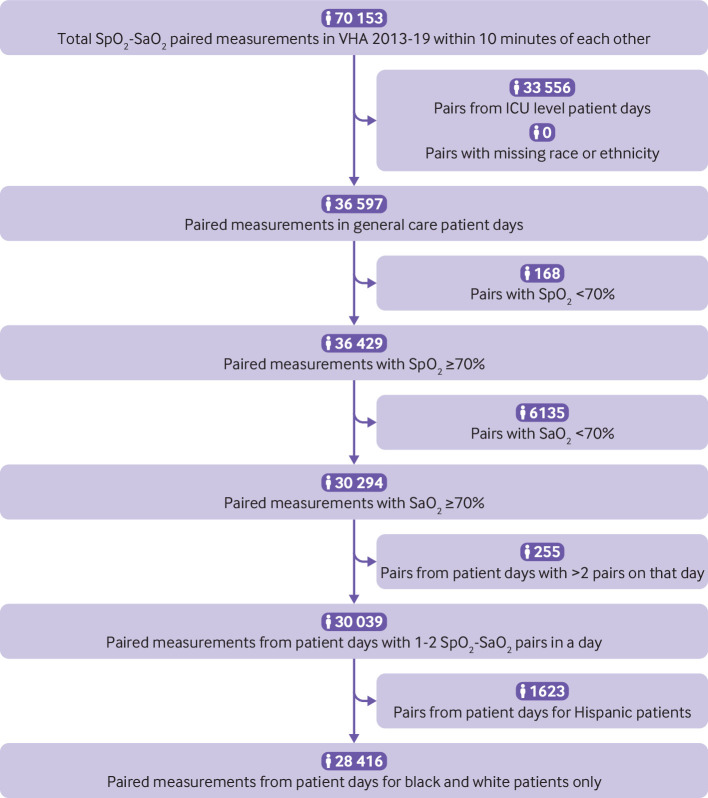

Click To Enlarge: Cohort flow diagram. SaO2=arterial blood gas reading; SpO2=pulse oximetry reading; VHA=Veterans Health Administration; ICU=intensive care unit; black=non-Hispanic black; white=non-Hispanic white; Hispanic=Hispanic or Latino Source: National Library of Medicine

ANN ARBOR, MI — Research from the University of Michigan, Johns Hopkins and other medical centers has been raising concerns about the accuracy of pulse oximeters in certain racial groups almost since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The worry has been that the widely-used devices overestimated oxygen levels in Black patients, delaying critical treatment.

“When we thought about how a big a deal this could be, including getting more-invasive blood gases in many patients and changing every pulse oximeter across the hospital, we knew we really needed to see how big the problem was, so we did not over-react,” explained Valeria Valbuena, MD, of the University of Michigan Department of Surgery, lead researchers on a study involving veterans.

The study in BMJ uses data from more than 100 VHA hospitals to determine the scope of the pulse oximeter issue.1

“Unfortunately,” Valbuena advised, “the pulse oximetry bias problem is really bad and could be affecting huge numbers of patients. Our results suggest that, in the VA alone, there may be over 75,000 instances a year when low blood oxygen is missed in a Black veteran yet would have been detected if pulse oximeters functioned as well as they do in white veterans. It is incredibly important that we fix it soon.”

The study, which also involved the VA Center for Clinical Management Research in Ann Arbor, MI, sought to evaluate measurement discrepancies by race between pulse oximetry and arterial oxygen saturation as measured in arterial blood gas among inpatients not in intensive care. 2

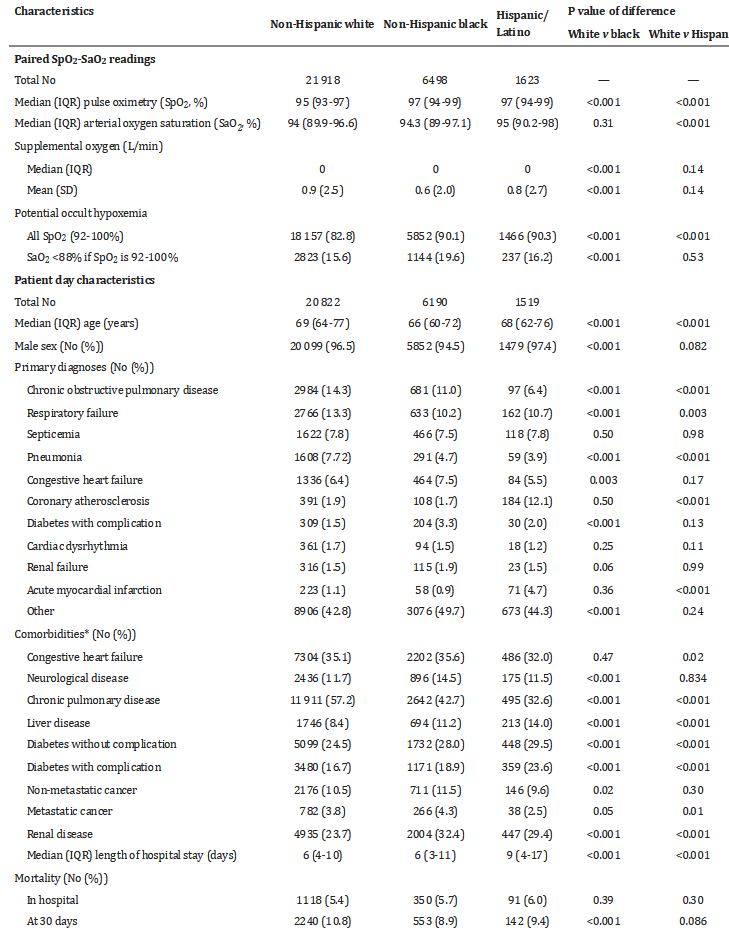

Click To Enlarge: Characteristics of SpO2-SaO2 pairs recorded in study population, by race and ethnic origin SaO2=arterial blood gas reading; SpO2=pulse oximetry reading; IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation. Source: National Library of Medicine

The multicenter, retrospective cohort study used electronic medical records from general care medical and surgical inpatients at the VHA from 2013 to 2019. Researchers focused on reports of occult hypoxemia, which is defined as arterial blood oxygen saturation (SaO2) of <88% despite a pulse oximetry (SpO2) reading of ≥92% and whether rates of occult hypoxemia varied by race and ethnic origin.

The study team identified 30,039 pairs of SpO2-SaO2 readings made within 10 minutes of each other; most, 73%, were among non-Hispanic white patients. Non-Hispanic Black patients and Hispanic or Latino patients accounted for 21.6% and 5.4% pairs in the sample, respectively.

“Among SpO2 values greater or equal to 92%, unadjusted probabilities of occult hypoxemia were 15.6% (95% confidence interval 15.0% to 16.1%) in white patients, 19.6% (18.6% to 20.6%) in black patients (P<0.001 v white patients, with similar P values in adjusted models), and 16.2% (14.4% to 18.1%) in Hispanic or Latino patients (P=0.53 v white patients, P<0.05 in adjusted models),” the researchers report. “This result was consistent in SpO2-SaO2 pairs restricted to occur within 5 minutes and 2 minutes. In white patients, an initial SpO2-SaO2 pair with little difference in saturation was associated with a 2.7% (95% confidence interval -0.1% to 5.5%) probability of SaO2 <88% on a later paired SpO2-SaO2 reading showing an SpO2 of 92%, but Black patients had a higher probability (12.9% (-3.3% to 29.0%)).”

That led to the conclusion that, across the VHA, when paired readings of arterial blood gas (SaO2) and pulse oximetry (SpO2) were obtained in general inpatient settings, Black patients had higher odds than white patients of having occult hypoxemia noted on arterial blood gas but not detected by pulse oximetry. “This difference could limit access to supplemental oxygen and other more intensive support and treatments for black patients,” the study emphasized.

The authors pointed out that the probability of occult hypoxemia in white veterans was 15.6% compared to 19.6% percent in Black veterans and 16.2% in Hispanic or Latino veterans.

In response to suggestions that a solution would be to target higher pulse oximetry readings in Black patients, the researchers discovered that paired readings—with one earlier in the day and one later—tended to be more consistent among white patients than Black patients.

Trusting the Device

“For white patients, if the pulse ox agreed with the earlier blood draw, then you could reasonably trust the pulse ox later,” said co-author Thomas S. Valley, MD, of the University of Michigan Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. “However, our results suggest you can’t place the same trust in pulse ox values over time for Black patients. Even if the pulse ox agreed with the earlier blood draw, later pulse ox measurements might miss low blood oxygen levels in Black patients.”

In May, a study published JAMA Internal Medicine suggested pulse oximeters used in healthcare centers didn’t give consistent readings, which raises the question of how racial and ethnic biases affected pulse oximetry readings among COVID-19 patients. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine also put forth concerns that those biases might have led to unrecognized or delayed recognition of eligibility for oxygen threshold-specific therapy. The Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston also was involved in the research.2

Their retrospective cohort study involved clinical data on 7,126 patients with COVID-19 from five referral centers and community hospitals in the Johns Hopkins Health System. The patients self-identified as Asian, 5.2%; Black, 39.3%; Hispanic, 17.7%; or white, 37.8%.

The study team analyzed 1,216 patients with oxygen saturation levels that were concurrently measured by pulse oximetry and arterial blood gas and determined that pulse oximetry tended to overestimate arterial oxygen saturation among Asian, Black and Hispanic patients compared with white patients.

“Separately, among 6,673 patients with pulse oximetry measurements and available covariate data, predicted overestimation of arterial oxygen saturation levels by pulse oximetry among 1,903 patients was associated with a systematic failure to identify Black and Hispanic patients who were qualified to receive COVID-19 therapy and a statistically significant delay in recognizing the guideline-recommended threshold for initiation of therapy,” the authors wrote.

Researchers advised that their study results pointed to an overestimation of arterial oxygen saturation levels by pulse oximetry “in patients of racial and ethnic minority groups with COVID-19 and contributes to unrecognized or delayed recognition of eligibility to receive COVID-19 therapies.”

Results indicated that occult hypoxemia occurred in 19 Asian (30.2%), 136 Black (28.5%) and 64 non-Black Hispanic (29.8%) patients compared with 79 white patients (17.2%).

“Compared with white patients, SpO2 overestimated SaO2 by an average of 1.7% among Asian (95% CI, 0.5%-3.0%), 1.2% among Black (95% CI, 0.6%-1.9%), and 1.1% among non-Black Hispanic patients (95% CI, 0.3%-1.9%),” researchers explained. “Separately, among 1,903 patients with predicted SaO2 levels of 94% or less before an SpO2 level of 94% or less or oxygen treatment initiation, compared with white patients, Black patients had a 29% lower hazard (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.63-0.80), and non-Black Hispanic patients had a 23% lower hazard (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89) of treatment eligibility recognition.”

The study added that 451 patients (23.7%) never had their treatment eligibility recognized, most of whom (247 [54.8%]) were Black. Even among the remaining 1,452 (76.3%) who eventually had recognition of treatment eligibility, Black patients had a median delay of 1.0 hour (95% CI, 0.23-1.9 hours; P = 0.01) longer than white patients.

No significant median difference in delay between individuals of other racial and ethnic minority groups and white patients was documented, however.

Background information pointed out that modern pulse oximeters provide a noninvasive estimate of arterial blood oxygen saturation levels based on the relative absorbance of two wavelengths of light and the pulsatile flow of arterial blood (SpO2). Past research has reported overestimation of SpO2 compared with SaO2 among individuals with skin of darker pigmentation compared with individuals with lighter pigmentation.

In light of mounting evidence of racial disparity, the Food and Drug Administration said in late June that it continues to evaluate all available information pertaining to factors that might affect pulse oximeter accuracy and performance.

“Because of ongoing concerns that these products may be less accurate in individuals with darker skin pigmentations, the FDA is planning to convene a public meeting of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee later this year to discuss the available evidence about the accuracy of pulse oximeters, recommendations for patients and health care providers, the amount and type of data that should be provided by manufacturers to assess pulse oximeter accuracy, and to guide other regulatory actions as needed,” it announced.

Public health officials still recommend use of the devices, however.

- Valbuena VSM, Seelye S, Sjoding MW, Valley TS, Dickson RP, Gay SE, Claar D, Prescott HC, Iwashyna TJ. Racial bias and reproducibility in pulse oximetry among medical and surgical inpatients in general care in the Veterans Health Administration 2013-19: multicenter, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022 Jul 6;378:e069775. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-069775. PMID: 35793817; PMCID: PMC9254870.

- Fawzy A, Wu TD, Wang K, et al. Racial and Ethnic Discrepancy in Pulse Oximetry and Delayed Identification of Treatment Eligibility Among Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(7):730–738. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.1906