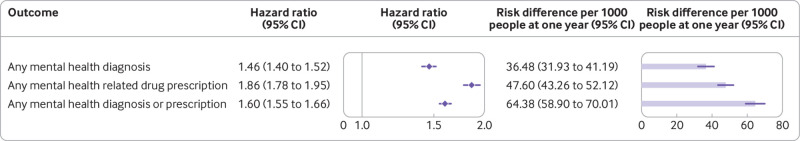

Click to Enlarge: Risks of incident composite mental health outcomes in covid-19 group compared with contemporary control group. Composite outcomes consisted of any mental health related drug prescription, any mental health diagnosis, and any mental health diagnosis or prescription. Outcomes were ascertained 30 days after the initial SARS-CoV-2 positive test result until end of follow-up. Hazard ratios are estimated through the follow-up and adjusted for age, race, sex, area deprivation index, body mass index, smoking status, number of outpatient encounters, history of hospital admission, use of long term care, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, dementia, diabetes mellitus, dysautonomia, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, estimated glomerular filtration rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and algorithmically selected high dimensional covariates. Risk differences are estimated at one year. Source: BMJ. 2022; 376: e068993.

ST. LOUIS — More than two years into the pandemic, studies are showing the long-term effects COVID-19 can have on the heart, lungs, kidneys and other organ systems. A new study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine and the VA St. Louis Health Care System shows COVID-19 also may have lasting effects on mental health.

While some previous studies had shown people with COVID-19 might be at increased risk of anxiety and depression, the new study is the first to show the risk of a broader range of mental health diagnoses a full year after infection. 1

“The pandemic disrupted a lot of lives. All of us experienced stress during the pandemic,” said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of Research and Education Service at VA St. Louis Health Care System and author of the study, which appeared in the British Medical Journal. “We wanted to know if people who had COVID-19 had it worse—are they exhibiting higher risk of mental health problems than the rest of the nation that did not get COVID-19?”

To answer that question, Al-Aly and his colleagues extracted data from the VA’s national healthcare databases. From those data they constructed a cohort of 153,848 U.S. veterans who survived the first 30 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection and two control groups—a contemporary group consisting of 5,637, 840 users of the VHA with no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and a historical control (predating the COVID-19 pandemic) consisting of 5,859,251 users of the healthcare system during 2017.

They followed the cohorts longitudinally to estimate the risks of a set of prespecified incident mental health outcomes in the overall cohort and according to care setting during the acute phase of the infection—that is, whether people were or were not admitted to hospital during the first 30 days of COVID-19.

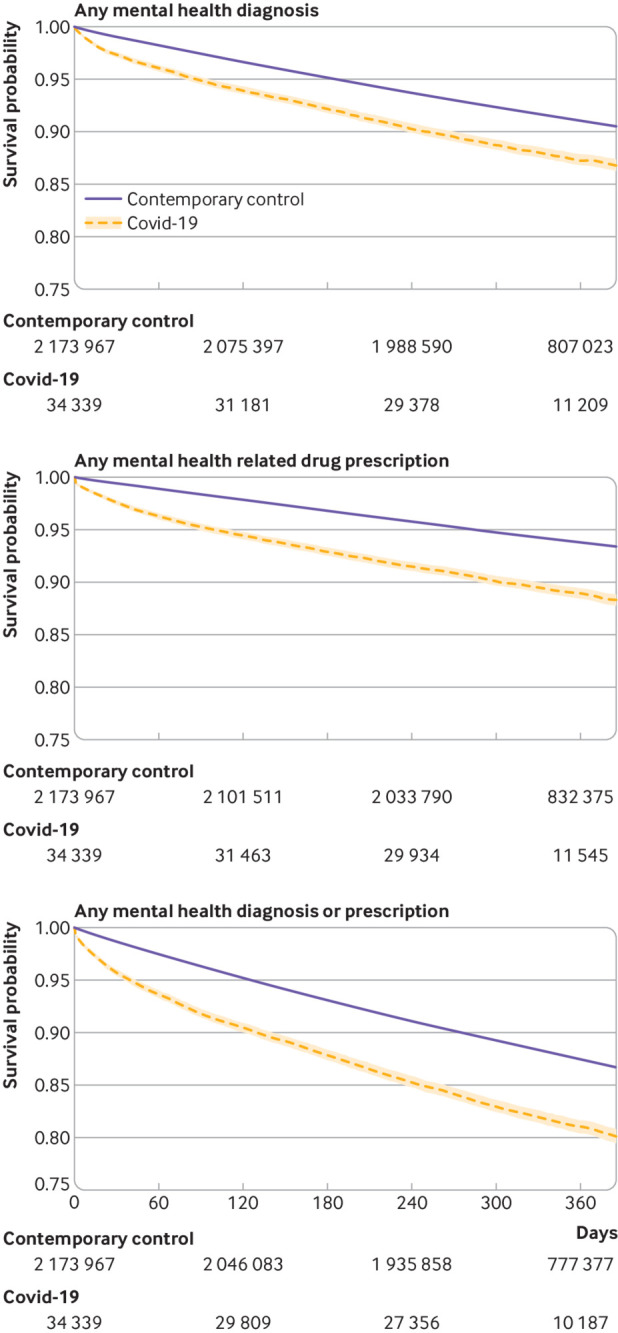

Click to Enlarge: Survival probability of incident composite mental health outcomes in covid-19 group compared with contemporary control group. Outcomes were ascertained 30 days after the initial SARS-CoV-2 positive test result until end of follow-up. Shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals. Numbers of participants at risk across groups are also presented. Source: BMJ. 2022; 376: e068993.

Their Key Findings

- People with COVID-19 show increased risks of incident mental health disorders (anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, stress and adjustment disorders, opioid use disorders, other (nonopioid) substance use disorders, neurocognitive decline and sleep disorders) compared with contemporary controls without SARS-CoV-2 or historical controls before the pandemic.

- The risks of mental health disorders were evident even among those who were not admitted to hospital, and were highest in those who were admitted to hospital for COVID-19 during the acute phase of the disease.

- People with COVID-19 showed higher risks of mental health disorders than people with seasonal influenza; people admitted to hospital for COVID-19 showed increased risks of mental health disorders compared with those admitted to hospital for any other cause.

The study does not explain the reason for the increases in these disorders, but, two-plus years into the pandemic, what scientists have already learned provides some clues, said Al-Aly. “[Investigators] have shown that SARS-CoV-2 is actually changing brain structure and biochemistry,” he said. “We think all of those irregularities that are caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus are leading to manifestations like depression, anxiety, PTSD and a lot of that. We think it is biologic—driven by the virus itself,” he said, adding that factors such as the emotional stress of having the virus and quarantining likely contributing to the increase.

The findings have important implications at the Individual, provider and policy level, said Al-Aly. For individuals experiencing the psychologic effects of COVID-19, the message is that they are not alone and should seek help early on. At the provider level, he says, it is important to know that COVID-19 is associated with increased risk of mental health problems. “When [providers] see people in the clinic who have had COVID, they should ask how they are doing—are they sleeping OK, have they been depressed or had suicidal thoughts?” he said. “A lot of time you have to get it out of patients to get them diagnosed and treated, and that is very important”.

“At the broader policy level,” he continued, “I think the main messages is that all of us endured some stress during the pandemic, but those with COVID-19 had it much worse. Nearly 18 million people in the U.S. have had COVID-19, and this is going to create a wave of people with anxiety and depression. I think we need to have programs and policies and pay attention to this now. … We need to make sure we are keeping a vigilant eye to be sure we are preventing this from becoming another crisis down the road.”

Al-Aly advised in a linked opinion piece, “Altogether, the findings suggest that people with COVID-19 are experiencing increased rates of mental health outcomes, which could have far-reaching consequences. The increased risk of opioid use is of particular concern, especially considering the high rates of opioid use disorders pre-pandemic. The increased risks of mental health outcomes in people with COVID-19 demands greater attention now to mitigate much more serious downstream consequences in the future.”2Al-Aly emphasized that the study’s findings shouldn’t be used to “gaslight or dismiss long COVID as a psychosomatic condition or explain the myriad manifestations of long COVID as the result of mental illness.”

“This dismissal is contrary to scientific evidence and is harmful to patients and communities,” he argued. “Mental health disorders represent one part of the multifaceted nature of long COVID, which can affect nearly every organ system (including the brain, heart and kidneys). Our results should be used to promote awareness of this risk among people with COVID-19 and to guide efforts for the early identification and treatment of affected individuals.”

Aly suggested that thinking about SARS-CoV-2 be “reframed.” While generally considered a respiratory virus, Al-Aly emphasized that it is “a systemic virus that may provoke damage and clinical consequences in nearly every organ system—including mental health disorders and neurocognitive decline.”

- Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with COVID-19: cohort study. BMJ. 2022 Feb 16;376:e068993. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068993. PMID: 35172971; PMCID: PMC8847881.

- Al-Aly Z. Mental health in people with COVID-19. BMJ. 2022 Feb 16;376:o415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o415. PMID: 35172969.