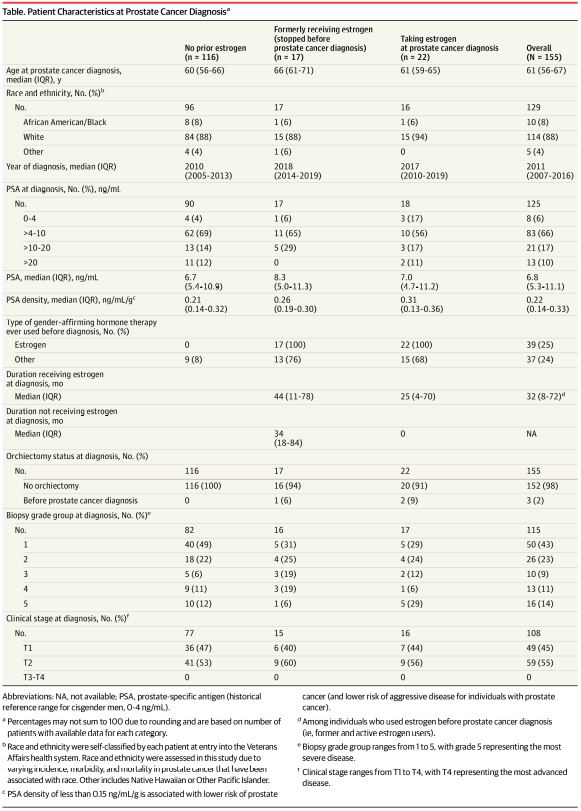

Click to Enlarge: Abbreviations: NA, not available; PSA, prostate-specific antigen (historical reference range for cisgender men, 0-4 ng/mL).

a. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding and are based on number of patients with available data for each category.

b. Race and ethnicity were self-classified by each patient at entry into the Veterans Affairs health system. Race and ethnicity were assessed in this study due to varying incidence, morbidity, and mortality in prostate cancer that have been associated with race. Other includes Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

c. PSA density of less than 0.15 ng/mL/g is associated with lower risk of prostate cancer (and lower risk of aggressive disease for individuals with prostate cancer).

d. Among individuals who used estrogen before prostate cancer diagnosis (ie, former and active estrogen users).

e. Biopsy grade group ranges from 1 to 5, with grade 5 representing the most severe disease.

f. Clinical stage ranges from T1 to T4, with T4 representing the most advanced disease. Source: JAMA Network

DURHAM, NC — Because of the risks of prostate removal—leakage of urine and problems with sexual function—the prostate usually is left intact in transgender women. But that also means transgender women are potentially at risk for prostate cancer, even if they have had gender-affirming surgery.

Aside from nonmelanoma skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in the United States. It is also highly treatable if detected early. But little is known about how often transgender women are diagnosed with prostate cancer.

A new study out of the Institute for Medical Research at the Durham, NC, VAMC has found that prostate cancer among transgender women is more common than previous evidence suggested but that the rate of prostate cancer diagnosis in transgender women is lower than the rate among cisgender men. The research letter was published in JAMA.1

In the largest study of its kind, researchers queried VA medical records to identify patients with International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for prostate cancer and transgender identify, finding a total of 449 patients. They then reviewed those patients’ medical records by hand to confirm that they had prostate cancer and were transgender women, said Amanda De Hoedt, MS, director of the Freedland Research Group at the institute.

“Reviewing these patients’ medical records, we were able to capture data about each patient’s medical history, including use of gender-affirming hormone therapies, prostate specific antigen (PSA) lab values—which are used to screen for prostate cancer—and clinical stage and grade of their prostate cancer,” De Hoedt said.

In addition to findings of the previously unrecognized prevalence of prostate cancer in transgender women and the lower rate of prostate cancer diagnosis in transgender women vs. cisgender men, the researchers observed a lower percentage of Black transgender women with prostate cancer compared with Black cisgender men.

Lower Rates

“We need to do further research to understand why rates of prostate cancer diagnosis are lower in transgender women, but possible explanations include lower rates of screening due to barriers such as stigma or lack of prostate cancer risk awareness or misinterpretation of what ‘normal’ screening thresholds should be among patients taking estrogen,” De Hoedt said. “The lower rates of prostate cancer within Black transgender women suggest there may be additional disparities at the intersection of race and gender identity.”

The researchers also observed that transgender women who received estrogen had more aggressive disease; however, the number of patients was small, and they were unable to do a formal statistical analysis, she said, adding, “This could be due to the delayed diagnosis or selection of more aggressive cancer cells; this will require further investigation in the future.”

De Hoedt, who oversees a team of 150 research staff to conduct urologic and oncologic research within the VA, said the new study is a natural extension of the research by the group, which has been researching prostate cancer for more than 20 years.

“There are over 1 million veterans with prostate cancer within the VA system, making this an important disease to study in a veteran population,” she said. “The availability of over 20 years of electronic medical records allowed us to capture detailed data presented in the study.”

Much of the group’s work focuses on evaluating health disparities according to factors such as race and socioeconomic status, De Hoedt said. “We realized that there were very few publications on prostate cancer in transgender women. We hoped to explore how common prostate cancer is among transgender women and if any health disparities exist.”

De Hoedt said the study’s findings show that physicians and patients should be aware of prostate cancer risk so that they can be screened. “More support for future research is needed to better evaluate what the best prostate cancer screening and treatment plans are for transgender women,” she said.

De Hoedt encouraged clinicians: “If you have a patient who is a transgender woman, please discuss the risk of prostate cancer with her and provide her with guidance on screening recommendations.”

- Nik-Ahd F, De Hoedt A, Butler C, Anger JT, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR, Freedland SJ. Prostate Cancer in Transgender Women in the Veterans Affairs Health System, 2000-2022. JAMA. 2023 Apr 29:e236028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.6028. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37119522; PMCID: PMC10148974.