LOS ANGELES — While healthcare access and use is a subject of national concern and considerable study, such studies often have failed to capture of subtleties of the healthcare experience of the American Indian and Alaskan Native (AIAN) population.

A limitation of these studies is that they are typically based on data from large national or state surveys, which often lack sample size and may generate limited information about potential factors such as tribal enrollment, preferences for culturally-specific healthcare and behaviors related to health that may affect the population’s consumption of goods and services, according to the authors of a new study designed to address that gap.1

The study, published recently in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, sought a deeper understanding of factors that may influence healthcare access and utilization among AIAN living in an urban area by examining data from a cross-sectional survey of AIANs in Los Angeles County, said Andrea Garcia, MD, a physician specialist at the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and the study’s first author. Los Angeles County has the largest AIAN population in the nation.

The survey of AIANs was conducted June to October 2016 by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health in partnership with three large AIAN community-based organizations in Los Angeles County. Primary data collection was carried out at these organizations’ facilities and events using purposive sampling, whereby a systematic approach to recruitment and administration was undertaken and clear delineation of the eligible pool of AIANs were identified.

“This approach was necessary because survey research has historically fielded small sample sizes in this population principally as a result of the community itself being smaller than the general population, cost of reaching this hard-to-reach group, known trust issues with the government, among other barriers,” Garcia and her colleagues wrote.

The survey instrument was divided into four parts: sociodemographic characteristics, including tribal enrollment status; health insurance coverage and Indian Health Service (IHS) eligibility ad use; opinions and preferences about AIAN clinics; and questions that screened for depression. Staff at the AIAN community-based organizations were trained to distribute the 4-page, self-administered paper questionnaire to AIAN clients upon check-in at their facilities.

To better interpret project findings and generate culturally relevant contexts, qualitative feedback was gathered at a community forum held in Spring 2018. Because recruitment of AIANs has historically been challenging, purposive sampling was employed to strategically identify a larger eligible pool, the researchers wrote. Among those who were eligible, 94% (496 individuals) completed the survey.

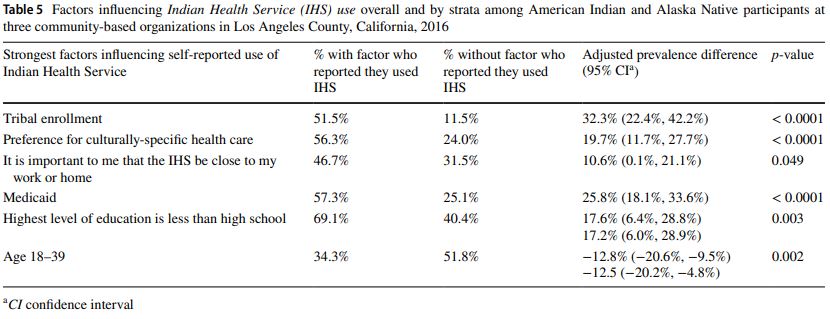

Some of the findings were what the researchers would have anticipated, Garcia said, but others came as a bit of surprise. “Given that IHS has specific eligibility criteria, we expected to find that those who are enrolled in a tribe are more likely to use the IHS,” Garcia said. “This was, indeed, the case.”

Less expected was that health insurance coverage was similar for those who were enrolled vs. not enrolled in a tribe, despite what the community forum may have implied, she said. Understandably, those who preferred culturally-specific healthcare were more likely to use the IHS. “Yet, despite this finding, viewpoints and opinions about the scope of IHS services, quality of care, trust and systems based considerations varied widely across the spectrum,” Garcia said.

The most surprising finding, she said, was that, despite a majority of participants indicating a preference for culturally specific health-care, key preferences such as seeing traditional healers, having doctors and staff that are AIAN or are at least culturally sensitive were ranked lower than preferences having to do with providing comprehensive care. “That said, it makes practical sense that people would want to ensure their basic medical needs are met first,” she said.

Garcia said the study’s utilization of both quantitative and qualitative approaches to understanding health-care access and utilization of an urban AIAN population makes it different from other studies. “The qualitative data collection was unique in that it gave the local community the ability to interpret and frame the findings in a way that other studies typically do not account for,” she said. “As a result, there was a juxtaposition of what participants found important as compared to what the initial study design may have otherwise explored.”

She said the study’s findings hold implications from both a research perspective and health systems perspective. “From a research perspective, the implications are that richer information can be gleaned from using a mixed methods approach and working more intentionally with historically resilient communities,” she said. “From a health systems perspective, our findings helped identify factors which may assist in increasing health care access and utilization among AIAN who reside specifically in urban areas.”

There are different perceptions and factors that impact health-care access and utilization among AIAN who specifically reside in urban areas, Garcia said. “Opportunities exist to provide targeted education and outreach and decrease barriers to comprehensive care. Provision of culturally appropriate care may be an appropriate avenue to increase healthcare access and utilization for AIAN who reside in urban areas.”

- Garcia AN, Venegas-Murrillo A, Martinez-Hollingsworth A, Smith LV, et. al. Patterns of Health Care Access and Use in an Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Population. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023 May 18:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40615-023-01624-3. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37202652; PMCID: PMC10195651.