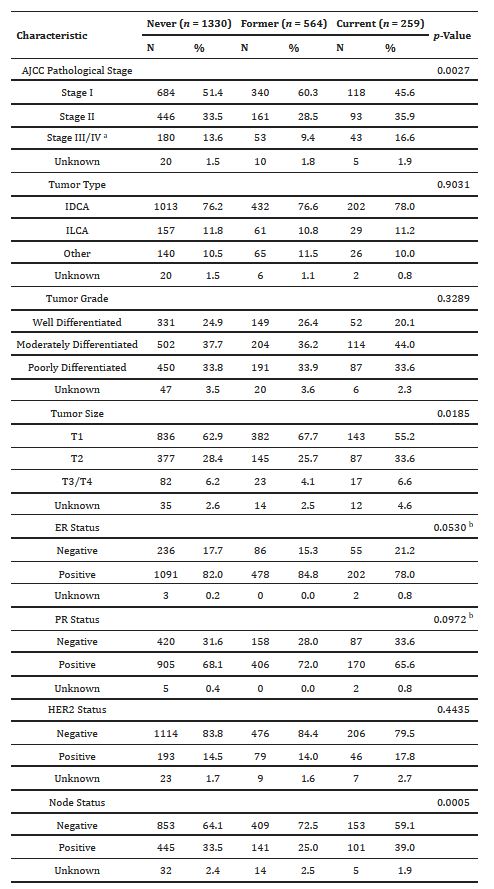

Click to Enlarge: Clinicopathological characteristics for 2153 women with breast cancer enrolled in the CBCP 2001–2016.

a To comply with HIPAA guidelines for presenting data in cells with N < 11, stage III and IV have been combined here. The p-value presented here was calculated with Stage III and IV as separate factors.

b Fisher’s exact test was used instead of chi-square test due to small cell size of less than 5.

Source: Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Apr; 19(7): 4084.

BETHESDA, MD — Largely because of its association with conditions such as lung cancer and cardiovascular/pulmonary diseases, cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States, with about 480,000 deaths each year attributable to the habit.

Smoking is more common among men in the United States at around 15%, but more than 12% of adult females were current smokers in 2019, according to a new study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.1

“While a number of studies suggest that smoking is a moderate risk factor for breast cancer, whether smoking influences tumor characteristics or survival is less clear,” wrote researchers from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and Walter Reed National Military Medical Centers and colleagues. “Identification of tumor phenotypes enriched in smokers may evince the underlying effects on tumor development.”

The study team pointed out that the enrichment of TP53 mutations in breast tumors from smokers could help promote the basal-like subtype, which is characterized by high rates (80%) of TP53 mutations. At the same time, it noted, cigarette smoking reportedly has anti-estrogenic effects, which could reduce the risk of estrogen receptor (ER) positive tumors.

Researchers also explained that nicotine promotes the proliferation of human breast cancer cell lines and also might result in larger tumor sizes in smokers vs. in nonsmokers.

Because of that, the authors sought to determine whether smoking status was associated with tumor characteristics and survival among female breast cancer patients. To that end, researchers investigated the relationships between smoking, pathological characteristics and outcomes in 2,153 women diagnosed with breast cancer from 2001-2016.

Patients were classified as never, former or current smokers at the time of diagnosis. Most, 61.8%, never smoked, followed by former smokers 26.2% and current smokers at 12.0%.

The researchers advised that, after adjustment for demographic variables, body mass index and comorbidities, tumor characteristics were not found to be significantly associated with smoking status or pack-years smoked.

On the other hand, 10-year overall survival was determined to be significantly lower for former and current smokers compared to never-smokers (p = 0.0105). Breast cancer specific survival did not differ significantly between groups (p = 0.1606), the authors added.

“Although cigarette smoking did not alter the underlying biology of breast tumors or breast cancer-specific survival, overall survival was significantly worse in smokers, highlighting the importance of smoking cessation in the recently diagnosed breast cancer patient,” the study concluded.

Even though data from the study did not suggest that cigarette smoking is associated with an enrichment of any tumor characteristics or breast cancer-specific survival, the study cautioned that nicotine and its metabolites have been detected in breast fluids from nonlactating smokers, and many of the carcinogens in tobacco smoke cause mammary tumors in animal models. They said that raises the risk that smoking-derived carcinogens might be present in the breast and increase the risk of breast cancer.

The authors also suggested that other factors could be in play, noting, “Differences in tumor stage, size and lymph node status, which reflect the time at which a tumor is resected, may be attributable not to smoking-derived carcinogen exposure in the breast but rather to other factors, such as decreased adherence to mammographic screening. In a study of 89,058 women enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative, current smokers were significantly less likely to undergo mammographic screening with concomitant higher stage breast cancer diagnoses.”

On the other hand, they said, former smokers were much more likely to undergo mammography. Their regular screenings could partially explain the lower rates of metastatic lymph nodes in former smokers detected in this study.

“The association of smoking with breast cancer biomarkers has been mixed. In our study, no significant association was detected between smoking status and ER, PR, or HER2 status,” the researchers explained. They added that past research also has been inconsistent, although the “data suggest that the hypothesized antiestrogenic effects of cigarette smoking do not reduce the risk of ER+ tumors.”

“As with tumor characteristics, the association between cigarette smoking and BCSS is controversial,” they added. “In our study, smoking status was associated with overall survival, but not BCSS. While some studies have found no association between smoking and BCSS, a number of other studies have found significant associations.”

Length of follow-up could explain some of the differences, with those having longer periods being more likely to show an effect. The length of follow-up in the current study was 8.1 years (7.42 years, 9.33 years and 8.32 years for current, former and never-smokers, respectively) compared to follow-up 50% longer or more in previous studies.

“Meta-analysis found that, while all-cause mortality was significantly associated with smoking across all time periods, smoking was associated with BCSS only for those with follow-up >10 years,” the authors wrote. “Thus, we do not exclude the possibility that there is a long-term effect of smoking on breast cancer-specific survival if such effects occur after 10 years. In contrast, overall survival, despite adjusting for comorbidities, was significantly lower for both former and current compared to never-smokers. These results suggest that smoking has general, rather than breast-specific, effects on health status.”

- Darmon S, Park A, Lovejoy LA, Shriver CD, Zhu K, Ellsworth RE. Relationship between Cigarette Smoking and Cancer Characteristics and Survival among Breast Cancer Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Mar 30;19(7):4084. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19074084. PMID: 35409765; PMCID: PMC8997894.