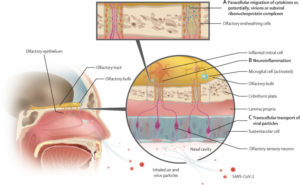

Potential pathways by which SARS-CoV-2 can infect the olfactory bulbs and generate inflammation

(A) Paracellular migration; molecules or virions can be transported across the cribriform plate through intercellular gaps between the olfactory ensheathing cells or within empty nerve fascicles. (B) Sterile neuroinflammation; immunological response marked by proinflammatory mediators (ie, cytokines and chemokines) that are activated by the virus, which has an initiating but secondary role. (C) The transcellular (trans-synaptic) transport pathway; virions could be transferred across the cribriform plate through anterograde synaptic transport.

WRIGHT-PATTERSON AFB, OH — In the early days of the pandemic, Col. Michael Xydakis, MD, a director at the Air Force Research Laboratory, was intrigued by reports of anosmia occurring with COVID-19. In the realm of respiratory viruses, he immediately suspected something was different, even sinister, about the loss of smell that so often occurred with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

An otolaryngologist with a subspecialty background in olfaction and rhinology, Xydakis had spearheaded the traumatic brain injury research for the U.S. Air Force a decade earlier. He had done research with olfactory impairment in head trauma and had run specialty clinics at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center on combat casualty care.

The olfactory loss he was hearing about sounded more like the result of a brain injury than a typical upper respiratory virus. “I knew there was something problematic going on,” he told U.S. Medicine. “I have seen this presentation before in blast- injured troops with head trauma.”

A year and a half and reviews of hundreds of studies later, Xydakis and a team of colleagues have published a paper in The Lancet that not only supports his early suspicions but also offers an important warning for physicians who treat patients with COVID-related anosmia.1

Different Types of Olfactory Dysfunction

In the paper, the researchers aggregated three different types of olfactory dysfunction after viral infection:

- Conductive (obstructive) or mechanical losses (e.g., congestion), such as congestion resulting from the blockage of inspired air due to local inflammation and edema of mucosal tissue in the olfactory cleft and upper nasal passages

- Sensorineural (olfactory epithelium and cranial nerve 1) dysfunction, which can be subdivided into two types: altered quantity or function of odorant-binding receptor molecules and neuropraxia or dysfunction of olfactory sensory neurons

- Central (olfactory bulbs and brain) dysfunction, which could be further subdivided into top-down effects on central olfactory dysfunction (e.g., acute head trauma or Parkinson’s disease) or pathosis isolated to the olfactory bulbs.

“The kind of transitory dysfunction you see with other viruses is almost exclusively obstructive loss,” says Xydakis. “It is congestion, so that results from the blockage of inspired air so the aromatic compounds just don’t get up to the receptors.”

With COVID-19, however, “it’s like a switch,” he said. “Patients will literally present the next day with complete loss of smell, but they don’t have the runny nose that goes along with that.” That tells you that sensorineural and central mechanisms are involved.

Long-term Olfactory Dysfunction

In most cases of COVID-19, olfactory function returns rapidly along with the resolution of other symptoms. The median time of recovery from the symptom’s first manifestation is approximately 10 days. In some cases, however, residual inapparent hyposmia, along with perceptual distortions, can persist.

In people with COVID-19 whose olfactory function has not returned to baseline, it is not clear whether chronic olfactory impairment is due to irreversible damage of the intranasal primary olfactory neurons embedded in the epithelium of the nasal vault, damage to the olfactory bulb or dysfunction within other CNS pathways.

Regardless, he says, long-term olfactory impairment could portend more serious problems.

“One of the take-away messages from this paper is that survivors of COVID-19 may be at risk of accelerated onset or progression of neurodegenerative disease, so they need to be studied longitudinally over time, especially with cognitive profiling,” said Xydakis, adding that sense of smell is a distinctive and specific symptom to monitor, unlike ubiquitous and nonspecific symptoms of illness like fatigue or brain fog that are also common in long-term COVID-19.

He advises physicians pay attention to COVID-19 patients with chronic loss of smell. “If you have patients who are coming to you three or six months after recovering from COVID and they have a persistent olfactory impairment, particularly if they have perceptional distortions such as olfactory hallucinations or parosmias—that is, foods don’t taste or smell the same as they did prior to infection—follow these patients and assess them for long-term risk of neurologic disease.”

Xydakis says there is great potential that someday more robust olfactory tests and neuroimaging tests will be able to determine neurologic impairment in a patient population. “With all of the unprecedented interest right now and all of the research going on, one of the silver linings that may come out of this public health and national security crisis is that science will continue to move forward at a rapid pace to develop these physiologic tests we need to identify these patients early on,” he said. “We need to go after the kindling as well as the fire!”

Earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic, Xydakia led a study that advised clinicians evaluating patients with acute-onset loss of taste or smell—especially nonconductive low—should suspect SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“We have observed that traditional nasal cavity manifestations, as seen in other upper respiratory infections (e.g., rhinovirus, influenza, and adenovirus), are commonly absent in patients with COVID-19,” the study team wrote in The Lancet Infectious Diseases last September. “We have also observed that SARS-CoV-2 does not appear to generate clinically significant nasal congestion or rhinorrhoea—i.e., a red, runny, stuffy, itchy nose. This observation suggests a neurotropic virus that is site-specific for the olfactory system. Although labeled as a respiratory virus, coronaviruses are known to be neurotropic and neuroinvasive. Finally, we and others have observed that anosmia, with or without dysgeusia, manifests either early in the disease process or in patients with mild or no constitutional symptoms.”

- Xydakis MS, Albers MW, Holbrook EH, et al. Post-viral Effects of COVID-19 in the Olfactory System and Their Implications. Lancet Neurol. 2021; 20 (9) (9): 753-761. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00182-4

- Xydakis MS, Dehgani-Mobaraki P, Holbrook EH, Geisthoff UW, et. al. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Sep;20(9):1015-1016. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0. Epub 2020 Apr 15. PMID: 32304629; PMCID: PMC7159875.