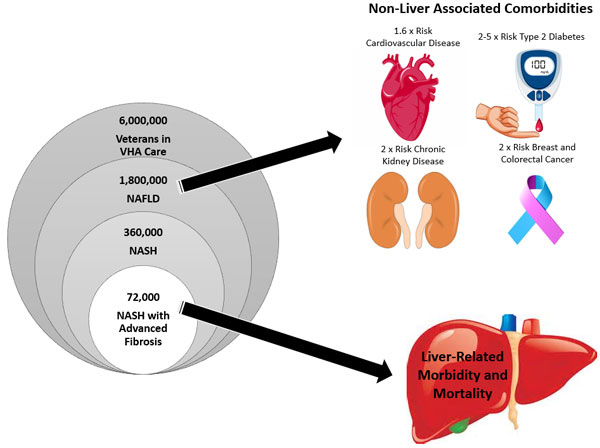

Click to Enlarge: Estimated prevalence of NAFLD in VA, and increased risk of comorbidities among patients with NAFLD. (Veterans in care is estimated from VA data). Source: VA NAFLD Considerations

Nearly 10% of Veterans Have Some Hepatic Fibrosis

HOUSTON — International experts recommend replacing the disease acronym nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD); the new terminology would allow additional reasons for liver disease and more clearly specifies the probable reason for illness, according to a recent veterans study.

The cross-sectional study conducted among patients at the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston and published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology examined both terms and found “perfect concordance” between NAFLD and MAFLD.

The study also determined that 40% of veterans in primary care can be diagnosed as MAFLD. Nearly 10% of veterans had at least moderate hepatic fibrosis, and more than two-thirds of these veterans with scarring of the liver tissue also had NAFLD/MAFLD.1

NAFLD refers to excessive fat in the liver in the absence of heavy alcohol drinking and the absence of active hepatitis C or B. MAFLD is fatty liver disease in the presence of signs of metabolic dysfunction (mainly diabetes and obesity) without specifying the absence of heavy alcohol or hepatitis C or B, study author Hashem B. El-Serag, MD, MPH, of the Houston VAMC explained in an email. El-Serag is also on the faculty of Baylor College of Medicine.

“Some (not all) experts proposed the MAFLD definition to accommodate the fact that many patients have an additional reason for liver disease other than NAFLD. They could have hepatitis C or B, or they could also be alcohol drinkers,” El-Serag told U.S. Medicine. “Another reason for the MAFLD definition is to confer more specificity to the likely reason for liver disease. Metabolic is much more specific than nonalcoholic.”

The study participants were primary care patients who were not seeking care for any specific liver disease. Patients with known advanced liver disease or hepatitis C or B were excluded. Participants were randomly selected to ensure that men and women, as well as people in different age groups between 40 and 80, were equally represented. Then, they were invited to complete a survey, provide blood and undergo a Fibroscan test to identify and quantify liver fat and fibrosis.

Of the 202 patients who met all criteria and completed the study requirements, the mean age was 50.9 years, and 112 participants were female. For race and ethnicity, 42.8% were white, 43.8% were Black, and 13.4% indicated other race/ethnicity. Self-reported ethnicity was 15.8% Hispanic and 34.2% non-Hispanic white. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 31.6 kg/m2, and the percentage of participants with overweight or obesity, diabetes and hypertension were 85.1%, 25.3% and 45.1%, respectively. More than one-half (56.9%) of participants were current alcohol users, with an average consumption of 0.35 drinks per day.

The study found almost 1 in 2 (40%) of the veterans in primary care had fatty liver, and almost 1 in 10 have fatty liver accompanied by liver scarring. “After eliminating heavy alcohol and active hepatitis B and C, the NAFLD and MAFLD definitions identify an identical group of patients,” El-Serag explained. Because the outcomes are similar, MAFLD may be easier to use clinically and better targets the underlying risk factors, the study reports.

Men at Higher Risk

In addition, the study found male sex was associated with a twofold higher risk of NAFLD/MAFLD. Also, a higher burden of metabolic traits (particularly obesity, diabetes and dyslipidemia) was linked with higher risk of NAFLD/MAFLD. There was a lower risk of NAFLD/MAFLD for non-Hispanic Blacks compared with non-Hispanic whites.

In 2020, a panel of international experts proposed the disease acronym MAFLD because it had become apparent that the threshold of current or past alcohol drinking is unclear, that both alcohol and non-alcohol causes of fatty liver can coexist in the same person and that fatty liver also can occur in the presence of and after the successful treatment of hepatitis C and B.

MAFLD is defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis (histological, imaging or blood biomarker evidence of hepatic steatosis) plus at least one of three metabolic criteria (overweight/obesity, Type 2 diabetes or evidence of metabolic dysregulation such as dyslipidemia). The important distinction between MAFLD and NAFLD is that MAFLD requires the presence of metabolic dysfunction, but doesn’t require the exclusion of patients with simultaneous heavy alcohol intake or other chronic liver diseases.

Studies have not yet thoroughly examined whether the criteria for MAFLD performs equally well or better than the NAFLD criteria for identifying patients with at least moderate fibrosis. NAFLD encompasses several stages of increasing severity and worsening prognosis, from simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Improving how the severity of fibrosis is identified may help better determine those at highest risk of poor outcomes.

Discussions over the terminology for NAFLD are ongoing. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and other pan-national liver societies are working to produce a DELPHI-based consensus.

The study’s findings are particularly important for the veteran population, which is disproportionately highly affected with obesity and diabetes, the study noted.

“Fatty liver related to metabolic dysfunction is very common in the VA primary care,” El-Serag advised. “It is the next/current frontier of chronic liver disease. [Being] overweight and obesity, diabetes and other metabolic dysfunction traits are highly predictive of the presence of fatty liver. Using NAFLD or MAFLD definitions is not likely to make a difference in tackling this condition.”

There is an urgent need to implement easily usable accurate algorithms at the level of primary care to identify and risk stratify patients with fatty liver disease, El-Serag added.

- Thrift AP, Nguyen TH, Pham C, Balakrishnan M, Kanwal F, Loomba R, Duong HT, Ramsey D, El-Serag HB. The Prevalence and Determinants of NAFLD and MAFLD and Their Severity in the VA Primary Care Setting. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jul 8:S1542-3565(22)00603-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.046. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35811043.