Need Is Especially Critical for Emergency Cesarean Delivery

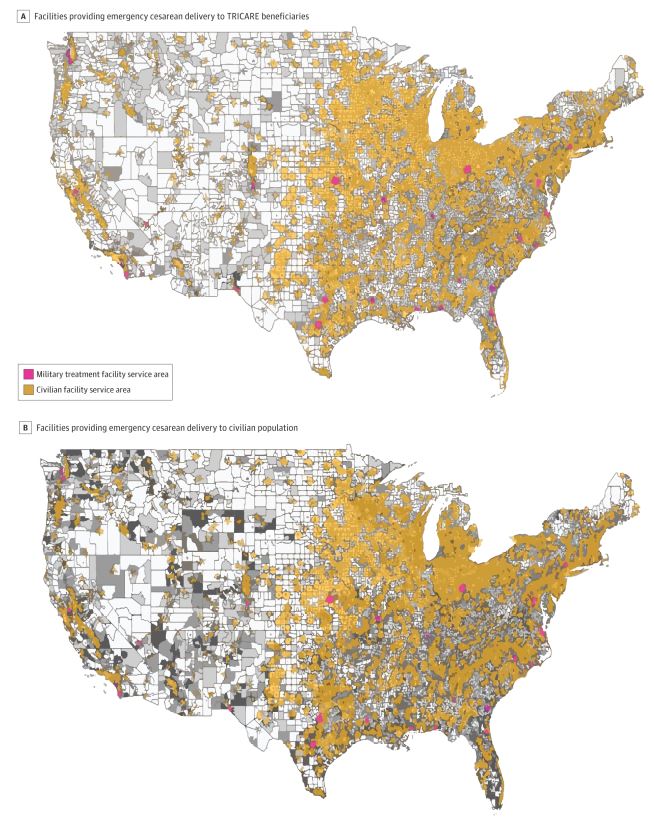

Click to Enlarge: Coverage of Population Within 30-Minute Travel Time to Facilities Providing Emergency Cesarean Delivery CareA, Gray gradient reflects the population density of female TRICARE beneficiaries normalized by the total female population of TRICARE beneficiaries, with lighter gray representing lower density and darker gray representing higher density. B, Gray gradient reflects the population density of the female civilian population at the county level, with lighter gray representing lower density and darker gray representing higher density.

BOSTON — If military treatment facilities offered emergency cesarean delivery and other high-quality obstetric care to civilians in underserved areas of the United States, according to a new study, it would not only significantly improve the health of expectant mothers and their babies but also potentially improve military readiness.

Maternal mortality rates in the United States are both higher than in comparable countries and are going in the wrong direction: U.S. rates increased to an estimated 16.9 pregnancy-associated deaths per 100,000 live births between 2006 and 2016 and currently has a higher maternal mortality ratio than more than 50 other countries.

In addition to racial disparities and other social issues, longer travel times to access obstetric care are associated with worse outcomes for pregnant women and their unborn children. Yet, as a report in JAMA Network Open pointed out, only about 61.6% of the U.S. population has access within 30 minutes to emergency obstetric care.1

Brigham and Women’s Hospital researchers partnered with military researchers and others to propose the solution. The study pinpointed 17 facilities with capacity to offer care in underserved areas, especially in rural communities.

“Offering emergency cesarean sections in underserved regions has the potential to not only improve care for pregnant patients in need of emergency access, but it also has the potential to address inequities and support military readiness,” said senior author Molly Jarman, PhD, MPH, of the Brigham’s Center for Surgery and Public Health (CSPH). “We have health care resources that need more patients, and we have patients in need of health care. While the maps of need and capacity do not overlap perfectly, when they do, we have an opportunity to open the door.”

“This could be a win-win for military MTFs and civilians,” added corresponding author Tarsicio Uribe-Leitz, MD, MPH, also of CSPH. “There is a lot to gain for both sides by reducing disparities, improving maternal care, and providing training and experience for military health care professionals.”

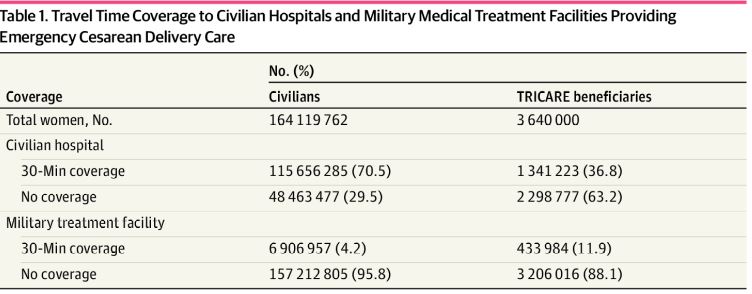

The cross-sectional study of 29 MTFs and 2,363 civilian hospitals potentially serving nearly 168 million female TRICARE beneficiaries and civilians also involved researchers from the Naval Medical Center San Diego, and the Center for Health Services Research at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD.

The study team pointed out that three MTFs were identified as the only facilities capable of providing emergency cesarean delivery care within a 30-minute travel time in those regions; it identified 14 additional MTFs that could improve access to emergency cesarean delivery care not provided by current civilian hospitals.

Background information in the article noted that many women in the United States, especially those in rural areas have limited access to obstetric care. The researchers sought to identify medical facilities within military and civilian geographic areas that could make possible military-civilian partnership in obstetric care and to assess whether civilian use of MTF could improve access to emergency cesarean delivery care in the U.S.

Click to Enlarge: Travel Time Coverage to Civilian Hospitals and Military Medical Treatment Facilities Providing Emergency Cesarean Delivery Care

The study team conducted the geospatial epidemiological population-based cross-sectional study from November 2020 to March 2021. The focus was on population coverage rates measured in percentage within 30-minute catchment areas, defined as areas that were within a 30-minute travel time to a medical facility capable of providing emergency cesarean delivery care.

Ultimately, they determined that 29 MTFs and 2,363 civilian hospitals were qualified to provide emergency cesarean delivery across the contiguous U.S. The study also identified 17 of 29 MTFs (58.6%) capable of providing emergency cesarean delivery care and that were located within 30-minute catchment areas.

“Of those, three MTFs were the only facilities capable of providing emergency cesarean delivery care within a 30-minute travel time in those regions, and 14 additional MTFs had catchment areas partially overlapping with civilian hospitals that also covered areas without alternative access to emergency cesarean delivery,” the authors wrote. “Expanded use of these 14 MTFs could enhance access to emergency cesarean delivery care not otherwise covered by current civilian hospitals.”

Researchers concluded that 58.6% of MTFs capable of providing emergency cesarean delivery care were located in areas with the potential to improve access to obstetric care within a 30-minute travel time. They advised that maintenance of MTFs in those “important access regions could be prioritized in the context of restructuring MTFs. This prioritization has the potential to improve access to emergency cesarean delivery care for underserved civilian populations in the US, particularly among those living in rural areas.”

The study pointed out that more than five million women in the United States live in the 1,085 of 3,007 counties (36%) that do not have available obstetric care or obstetric clinicians (i.e., maternity care deserts). Furthermore, another 10 million women live in counties with limited access to maternity care, defined as access to facilities, healthcare professionals and insurance.

Emergency Services

That is especially an issue with obstetric intensive care units (ICUs). “Although 87% of women in the U.S. live within 50 miles of a facility providing Level 3 obstetric care (i.e., care for complex maternal and fetal conditions and complications) and neonatal intensive care, only 61.6% of the population has timely emergency access (i.e., within 30 minutes) to obstetric care, with even fewer having access to Level 3 obstetric and neonatal care within 30 minutes,” the authors explained. “Longer travel times to obtain obstetric care have been associated with worse perinatal outcomes, especially when there is a delay in the receipt of emergency cesarean delivery services.”

The article pointed out that while the civilian healthcare system has substantial obstetric care disparities, with many women experiencing limited access to care, particularly in rural areas, similar problems could occur in the MHS with pressure to “rightsize” the system by closing or consolidating MTFs. It noted that the Government Accountability Office has recommended that the MHS examine the capabilities of civilian hospitals that surround MTFs before making any major changes to help avoid those issues.

“Collaboration between military and civilian health care professionals has been a catalyst for medical innovation since the American Revolution,” the authors recounted. “In trauma care, military-civilian partnerships have allowed civilian surgeons to incorporate wartime advancements into their practices, and military surgeons have been able to maintain their surgical skills during military drawdowns and peacetimes.”

Pointing to existing collaborations such as those at major trauma centers in Baltimore; Cincinnati; Jacksonville, FL; San Antonio and Miami, researchers strongly urged consideration of extending military-civilian collaborations beyond trauma care while addressing population health care needs in the United States.

The delivery of obstetric care, which is also the largest service line within the MHS, would be an obvious place to expand, they argued.

“Military-civilian partnerships may improve access to cesarean delivery care, supporting the dual MHS aims of ensuring the clinical readiness of the military medical force and the medical readiness of the military force as a whole, particularly among service members living in rural communities,” they added.

“Improved access to emergency obstetric care could save lives,” Jarman asserted. “We see this work as bringing together a solution for two separate issues—reducing preventable maternal mortality in the rural U.S. and the ongoing policy discussions on ‘right sizing’ the U.S. military health system.”

- Uribe-Leitz T, Matsas B, Dalton MK, et al. Geospatial Analysis of Access to Emergency Cesarean Delivery for Military and Civilian Populations in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142835. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42835