Nondisclosure Complicates Recruiting Process

Capt. Michelle Tsai, the behavioral health officer for the 4th Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division, reviews medical information in her office at the Joint Readiness Training Center June 17. Tsai, an Alexandria, Va., native, is here with the Raider Brigade in support of training operations for the unit’s upcoming deployment to Iraq. (Photo by Pfc. Luke Rollins)

BETHESDA, MD – As a common childhood diagnosis, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) also affects the pool of potential military applicants.

But it is not just the condition itself, which often can be successfully treated with stimulants and other medications, that is at issue. Mental health comorbidities are common with ADHD and can cause problems for recruits and the military.

A study led by researchers from the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences sought to assess attrition from military service in active component servicemembers diagnosed with ADHD, comparing them with controls. The study, with a surveillance period from January 2014 through Dec. 31, included any member of the Army, Navy, Air Force or Marine Corps who first entered military service in 2014. The results, published in MSMR, also assessed attrition rates and incidence rates of mental health diagnoses by treatment status—i.e., treated vs. untreated ADHD—with treatment defined as being dispensed a Food and Drug Administration approved ADHD medication at least twice within 181 days.1

The authors pointed out that early detection and treatment of ADHD might decrease the risk of developing comorbidities but that accession policy during the study period from 2014 to 2018 disqualified applicants who used ADHD medication for more than 24 months cumulative after age 14.

The study noted that nearly two-thirds (64.8%) of newly accessed ADHD cases in 2014 were identified after enlistment medical screening at Military Entrance Processing Stations (MEPS). Researchers advised that the post-MEPS ADHD cases accounted for nearly all, 99.1%, of the treated ADHD cases, with 91% receiving ADHD medication within six months of accession. Yet, the treated ADHD group had higher rates of attrition and incidence of mental health disorders during the follow-up period, they noted, adding, “These study findings highlight the problem of nondisclosure of ADHD among military applicants. Future changes to enlistment standards should consider the optimal way to promote applicant disclosure of ADHD during MEPS screening or for medical waiver review and should discourage withholding an ADHD diagnosis during enlistment.”

The key, according to the authors, could be changing enlistment standards to optimize or incentivize applicant disclosure of a preexisting ADHD diagnosis during MEPS screening or service specific medical waiver review.

“The ADHD accession policy selects less severe and higher functioning ADHD individuals, but nondisclosure of medical conditions, particularly behavioral health diagnoses, is a difficult problem for accession medical screening to resolve,” they explained. “Previous studies have discussed the problem that more recruits are dismissed annually for withholding an ADHD diagnosis than applicants who are truthful in disclosing the diagnosis.”

The study results suggested that the problem persists, despite numerous policy changes over the past two decades. In addition to encouraging ADHD disclosure in military applicants, the military should disincentivize nondisclosure by threat of disqualification or other punishment, the authors recommended.

Background information in the article described how ADHD is characterized by persistent impairing inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, with parents usually recognizing symptoms before their child reaches age 12. The prevalence of ADHD in U.S. children 2-17 years old ranges from 9-11%, while adult ADHD prevalence in the U.S. is estimated at 4.4%. Most, 62%, of children with ADHD in 2016 took medication.

“ADHD patients frequently have comorbid conditions such as mood, anxiety and substance use disorders, but early ADHD treatment with medication may convey some protection against these co-occurring conditions,” the article said.

ADHD Can Be Disqualifying

During 2000-2018, the prevalence rate of ADHD in the DoD ranged between 1.7% and 3.9% and has steadily declined since 2011, according to the report, which added that current DoD accession policy, DoD Instruction (DoDI) 6130.03 (updated in 2018), disqualifies military applicants with diagnosed ADHD if they meet any of the following conditions:

- had ADHD medication prescribed in the previous 24 months;

- had an educational plan or work accommodation after age 14;

- had a history of comorbid mental health disorders;

- had documentation of adverse academic, occupational or work performance.

Previously, based on updates to the policy in 2005 and 2010, disqualified applications if there had been medication use in the previous 12 months or for more than 24 months cumulative after the age of 14 years, respectively. In other words, the trends in policy change have been toward extending the time period that ADHD-diagnosed military recruits had to be without prescribed ADHD medication.

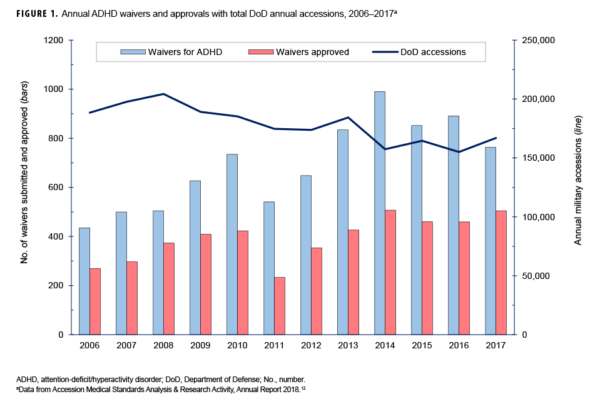

Among the results have been increasing waiver submissions for ADHD—mean of 560/year in 2006-20010 vs. 789/year) in 2011-2017—and percent applicant disqualifications (36.4%/year vs. 46.9%/year).

The authors pointed out that, in 2017, ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders were the fifth most frequent diagnoses resulting in medical disqualification of first-time enlisted active component military applicants. While a previous study evaluating ADHD accessions through waiver admissions to the Army found no change in retention rates, it was conducted in 2006 before the current policies were in place.2

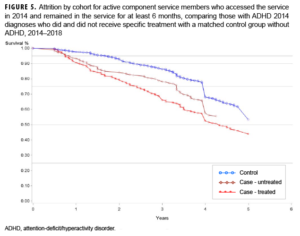

Researchers identified 996 servicemembers who were newly accessed into the military in 2014 and qualified as an ADHD case; of those, 334 were classified as treated with ADHD medication and 662 were classified as untreated.

“Compared to the untreated ADHD group, the treated group had relatively higher proportions of females, service members aged 20 years or older, members of racial/ethnic minority groups, Army members, and junior officers,” the authors wrote. “The untreated ADHD group had relatively higher proportions of Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force members compared to the treated ADHD group.”

The study found that nearly 40% of ADHD cases left military service within the first six months of the surveillance period and, therefore, weren’t defined as treated ADHD cases for purposes of the study.

After applying the requirement that servicemembers remained in the military at least six months, the ADHD group decreased to 616 individuals (331 treated with medication and 285 untreated), and the non-ADHD (control) group decreased to 911, according to the article. Especially affected was the Navy, where the proportion of untreated sailors decreased from 53% (n=296) to 12% (n=35).

“Compared to untreated ADHD and non-ADHD groups, the treated ADHD group had significantly higher crude incidence rates of all mental health disorders, with the highest rate observed for anxiety disorders (an individual servicemember could have had multiple mental health disorders),” the authors explained. “The untreated ADHD cohort’s incidence rates of mental health disorders were not statistically significantly different from the rates among those in the non-ADHD group.”

While the ADHD accession policy selects less severe and higher functioning ADHD individuals, the authors emphasized that nondisclosure of medical conditions, particularly behavioral health diagnoses, is troublesome for accession medical screening to resolve. They cited previous studies finding that more recruits are dismissed annually for withholding an ADHD diagnosis than applicants who are truthful in disclosing the diagnosis.

“Results of the current study suggest the persistence of this problem, even after multiple policy changes over the past 2 decades,” they added.

-

Sayers D, Hu Z, Clark LL. Attrition Rates and Incidence of Mental Health Disorders in an Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Cohort, Active Component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2014-2018. MSMR. 2021 Jan;28(1):2-8. PMID: 33523679.

-

Krauss MR, Russell RK, Powers TE, Li L. Accession standards for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a survival analysis of military recruits, 1995–2000. Mil Med. 2006;171(2):99–102.