SAN DIEGO — With about 4,000 new cases of colorectal cancer diagnosed each year, the VA has fought to increase screening for the condition, which is in the top five cancers afflicting veterans.

While those efforts have been successful, a new VA study suggested that initial screening is just half the battle, however. It found that delays in undergoing colonoscopy following an abnormal stool test significantly increase the risk of a colorectal cancer diagnosis and cancer-related death.

Making the situation even more complex is the overall lack of guidance on when and how follow-up should occur.

Samir Gupta, MD, chief of gastroenterology at the VA San Diego Healthcare System, was co-author of a study suggested that some patients and primary care providers misunderstand the results of abnormal stool blood screening tests. VA Photo by Christopher Menzie

“Currently, there is no national policy or standard for the clinically acceptable time interval between an abnormal FIT-FOBT result and diagnostic colonoscopy,” wrote authors of the study appearing recently in the journal Gastroenterology. “Time to colonoscopic follow-up varies widely in practice and across health care settings. A recommended interval that is too long can contribute to polyp progression and stage migration of colorectal cancer, risking the need for more aggressive and morbid treatment, as well as less favorable outcomes.”

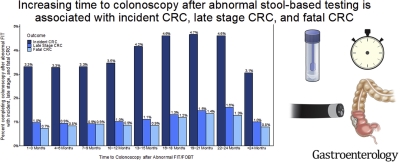

The retrospective study of more than 200,000 veterans determined that patients receiving colonoscopy more than 13 months after an abnormal stool blood test were up to 1.3 times more likely to have colorectal cancer, compared with those who had colonoscopy up to three months after the stool test.1

Furthermore, researchers from the San Diego and Los Angeles VA health systems and colleagues advised that the odds of an advanced stage of cancer at diagnosis were up to 1.7 times higher when colonoscopy was delayed beyond 16 months.

The cohort included veterans who had an abnormal fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or fecal occult blood test (FOBT)—the common stool blood screening tests require a follow-up colonoscopy to evaluate for precancerous and cancerous colorectal growths when abnormal.

Researchers emphasized that the optimal time interval for diagnostic colonoscopy completion after an abnormal stool-based colorectal cancer (CRC) screening test has been uncertain, which is why they examined the association between time to colonoscopy and CRC outcomes among veterans who underwent diagnostic colonoscopy after abnormal stool-based screening.

Specifically, the retrospective cohort study focused on veterans age 50-75 years with an abnormal FOBT or FIT between 1999 and 2010. The 204,733 participants had an average age of 61.

Results indicated an increased CRC risk for patients who received a colonoscopy at: 13-15 months (HR=1.13, 95%CI:1.00-1.27), 16-18 months (HR=1.25, 95%CI:1.10-1.43), 19-21 months (HR=1.28, 95%CI:1.11-1.48), and 22-24 months (HR=1.26, 95%CI:1.07-1.47).

Compared to patients who received a colonoscopy at 1-3 months, mortality risk was higher in groups who received a colonoscopy at: 19-21 months (HR=1.52, 95%CI:1.51-1.99) and 22-44 (HR=1.39, 95%CI:1.03-1.88), while odds for late stage CRC increased at 16 months, researchers pointed out.

“Increased time to colonoscopy is associated with higher risk of CRC incidence, death, and late stage CRC after abnormal FIT/FOBT. Interventions to improve CRC outcomes should emphasize diagnostic follow-up within 1 year of an abnormal FIT/FOBT result,” the study team concluded.

Lead researcher Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil, a gastroenterologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, identified a colonoscopy within one year of an abnormal stool test as essential to improve colorectal cancer outcomes.

“These findings extend current knowledge about the clinical implications of time to follow-up after abnormal FIT-FOBT,” the researchers wrote. “Further work should include [efforts] that address barriers to [undergoing] colonoscopy after abnormal non-colonoscopic screening results and policies to encourage the routine monitoring of follow-up rates.”

The authors said their study is the first to link the risk of death linked to delays in undergoing a colonoscopy following an abnormal stool blood test.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, stool tests have especially increased because of the convenience and safety of home testing and the hesitancy of patients to go to a health care facility for colonoscopy.

Co-author Samir Gupta, MD, chief of gastroenterology at the VA San Diego Healthcare System, noted that some patients and primary care providers don’t understand the importance of having colonoscopy after an abnormal stool test.

“Some patients and providers even explain these results incorrectly, attributing abnormal results to hemorrhoids, something that was eaten, or other problems,” Gupta posited. “They don’t believe the results. The results of this study should raise awareness that delaying colonoscopy after an abnormal stool test can have major consequences, including increased risk for cancer diagnosis, late-stage cancer at diagnosis, and death from colorectal cancer. These findings can also help motivate patients and providers to make sure colonoscopies are completed after an abnormal test.”

Noninvasive Tests

Gupta suggested the problem with follow-up will become more severe because of the increasing popularity of noninvasive tests for colorectal cancer screening, explain, “With stool tests, such as FIT and FIT-DNA, already covered by most insurance companies and with promising new blood-based screening tests for colorectal cancer under study in large trials. The challenge of ensuring complete screening, including initial completion and follow through to colonoscopy after an abnormal test, is likely to grow substantially.”

He has helped the VA find ways to increase colorectal cancer screening, including the use of mailed FIT assays. Gupta was a key participant in a meeting convened in the summer of 2019 to answer key questions regarding mailed FIT. The report in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians also dealt with the issue of follow-up, stating, “The effectiveness of mailed FIT programs relies on the successful completion of colonoscopy after abnormal stool test results, as failure to complete a follow‐up is associated with poorer CRC outcomes.2

The report also addressed which strategies might be most effective in ensuring abnormal FIT follow-up.

“There are several steps in completing a follow‐up colonoscopy,” the panel wrote. “Individuals with an abnormal stool test result should be informed of their result, a colonoscopy should be scheduled and completed in a timely matter, colonoscopy results should be returned to the individual, and a treatment consultation should be arranged if cancer is found.”

It added, “Most studies of abnormal FIT follow‐up focus on colonoscopy completion as the primary outcome. Because follow‐up colonoscopies are the means of identifying and removing precancerous polyps (for cancer prevention) and for diagnosing early‐stage cancers (to reduce the risk of CRC mortality), it is essential that programs achieve high rates of follow‐up colonoscopy completion.”

The report also pointed out that colonoscopy completion rates after an abnormal stool test result range from 30% to 82% in screening trials, demonstrating high variability.

One specific challenge faced by the VA is a history of prolonged wait times for routine medical care, including elective outpatient procedures such as colonoscopy.

In an article in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, the authors from the VA Ann Arbor, MI, Healthcare System and the University of Michigan Health System, emphasized that wait times for colonoscopy following positive FOBT are associated with worse clinical outcomes only if greater than six months.3

The study team conducted a retrospective cohort study of veterans who underwent outpatient colonoscopy for positive FOBT in 2008-2015 at 124 VA endoscopy facilities. Defined as the main outcome measure was wait time (in days) between positive FOBT and colonoscopy completion, stratified by year and adjusted for sedation type, year and potentially influential patient- and facility-level factors.

During the study period, 125,866 outpatient colonoscopy encounters for positive FOBT occurred. Results indicated that the number of colonoscopies for the indication declined slightly over time (17,586 in 2008 vs. 13,245 in 2015; range 13,425-19,814). In 2008, median wait time across sites was 50 days (interquartile range [IQR] = 33, 75).

Yet, the authors advised, wait times for colonoscopy for positive FOBT have been stable over time. “Despite the perception of prolonged VA wait times, wait times for outpatient colonoscopy for positive FOBT are well below the threshold at which clinically meaningful differences in patient outcomes have been observed,” they concluded.

- San Miguel Y, Demb J, Martinez ME, Gupta S, May FP. Time to Colonoscopy After Abnormal Stool-Based Screening and Risk for Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan 29:S0016-5085(21)00325-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.219. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33545140.

- Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, Brenner AT, et. Al. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: Summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-sponsored Summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Jul;70(4):283-298. doi: 10.3322/caac.21615. Epub 2020 Jun 25. PMID: 32583884; PMCID: PMC7523556.

- Adams MA, Rubenstein JH, Lipson R, Holleman RG, Saini SD. Trends in Wait Time for Outpatient Colonoscopy in the Veterans Health Administration, 2008-2015. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Jun;35(6):1776-1782. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05776-4. Epub 2020 Mar 24. PMID: 32212093; PMCID: PMC7280466.