Higher Risk of Obesity Also Found

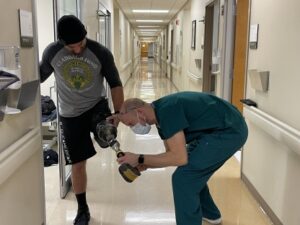

Tyler Cook (prosthetist) at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fixes retired U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Earl Granville’s prosthetics last year Photo by Alpha Kamara

BETHESDA, MD — Although amputations are medically necessary and could decrease pain, improve mobility and expedite return to activity, limb loss could negatively impact metabolic regulation and contribute to a higher risk of obesity, according to a recent military study.

The retrospective review published in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery compared long-term health outcomes after high-energy lower-extremity trauma between patients who underwent attempted flap-based limb salvage or amputation. The study fills a gap in long-term health data that can “help surgeons guide the decision between limb salvage and amputation in patients with limb-threatening trauma,” study authors suggested.1

Between 2001 and 2011, more than 1,200 U.S. military servicemembers experienced lower-limb amputations during military operations in the Middle East. Injuries to extremities sustained in combat often result from “high-energy mechanisms and often necessitate amputation or flap-based limb salvage,” according to the authors. To date, there hasn’t been a study comparing the impact on body mass index (BMI) and the development of metabolic disorders between previously healthy patients who sustained similar lower extremity injuries, the study reported.

This investigation was performed at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD. Additional study authors are affiliated with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD; Naval Medical Center Camp Lejeune in Jacksonville, NC; and William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, TX.

The researchers “performed a retrospective review of servicemembers who underwent flap-based limb salvage followed by unilateral amputation or continued limb salvage after combat-related, lower-extremity trauma between 2005 and 2011 and were treated within the Military Health System’s National Capital Region. There was a minimum 10-year follow-up. Patient demographic characteristics, injury characteristics, and health outcomes including BMI and development of metabolic disease (e.g., hyperlipidemia, hypertension, heart disease and diabetes) were compared between treatment groups. For patients who had undergone amputation, adjusted BMIs were calculated to account for lost surface area,” the study explained.

The participants were 110 patients who had long-term follow-up (mean of 12.2 years) following the injury; 56 patients underwent limb salvage. Of the 54 patients who underwent unilateral amputation, 35 patients underwent transtibial amputation, and 19 underwent transfemoral amputation. In this group, 39 patients underwent early amputation, and 15 patients underwent late amputation. The researchers found no difference in preinjury BMI. Obesity was defined as a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2, according to the study.

“Our study found that, after adjusting for limb loss, patients who underwent amputation had higher BMIs at one year or more after the injury, a higher rate of obesity and a greater increase in BMI from baseline after the injury,” co-author Benjamin Potter, MD, the Norman M. Rich Professor and chair of the Department of Surgery at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, told U.S. Medicine. “The development of metabolic comorbidities was common after both amputation and limb salvage. However, with the available data, we weren’t able to demonstrate a difference in risk for the development of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, heart disease or any comorbidity other than obesity.” Potter is also on staff at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

A patient’s body composition and metabolism can change after major trauma that results in amputation or limb salvage due to different physical demands, muscle atrophy and increased body fat. Following lower-extremity amputations, studies have found that decreased physical activity and comorbid conditions have led to increased risk of weight gain, Potter explained.

The study found that “23 patients (43%) who underwent amputation developed metabolic comorbidities, with four patients (7%) diagnosed with diabetes, 19 (35%) with hypertension, 14 (26%) with hyperlipidemia, three (6%) with heart disease and one (2%) with myocardial infarction. In addition, 27 patients (48%) who underwent limb salvage developed metabolic comorbidities, with two patients (4%) diagnosed with diabetes, 17 (30%) with hypertension, 17 (30%) with hyperlipidemia, one (2%) with heart disease and two (4%) who sustained a myocardial infarction,” the researchers pointed out.

The analysis also determined that “amputation was not associated with increased development of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, heart disease or any metabolic comorbidities compared with limb salvage,” study authors reported.

The authors explained that both patients who “underwent amputation or limb salvage experienced increased BMI at all-time points after the injury, and amputation patients had higher BMIs at year one, three, five, eight and 10. There was a significantly larger increase in BMI in the amputation group at three years, with larger increases at five, eight and 10 years compared to the limb salvage group.”

The proportion of obese patients in the amputation group at three years and five years was significantly higher, but by 10 years, the proportion of obese patients was not significantly different between treatment groups, according to the authors.

When comparing different amputation levels, the study found “no significant differences in BMI at 10 years or the rate of obesity. The amputation level also wasn’t associated with developing hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease or diabetes. Late amputation wasn’t associated with higher rates of obesity or associated comorbidities compared to early amputation, and patients who underwent late amputations followed similar BMI trajectories as patients who had amputation within six months of the injury,” the researchers explained.

“By the final follow-up, which was 10 years after the injury, 48% of patients who underwent limb salvage and 62% of patients who underwent amputation developed obesity,” Potter said. “The obesity rates observed in our treatment cohorts are higher than in the general American population, which was 39.8% between the ages of 20 and 39 years old in 2020.”

Potter notes the finding that “patients who underwent amputations after failed limb salvage followed a similar trajectory of BMI as those who underwent acute amputation.”

“While, in general, patients requiring early amputation have worse injuries than those continuing with limb salvage, we tried to make our treatment cohorts as comparable as possible by including only limb salvage patients requiring flap coverage,” Potter explained. “Even with improvements in amputation procedures and prostheses, our study did not detect substantial long-term health benefits with amputation compared with durable limb-preservation surgery focused on restoring function and diminishing pain. We believe that these findings should inform counseling and shared decision-making among patients and providers who are considering amputation or limb salvage when both are viable options after high-energy lower-extremity trauma.”

Limitations of the study, Potter said, include that patients were relatively young during the analysis, so the researchers can’t predict changes in obesity and metabolic comorbidities as patients enter later life. Also, the relatively small number of patients could have been inadequate to detect some differences. Lastly, limb salvage may not have been a reasonable option for some patients who were treated with amputation.

- Tropf JG, Hoyt BW, Walsh SA, Gibson JA, Polfer EM, Souza JM, Potter BK. Long-Term Health Outcomes of Limb Salvage Compared with Amputation for Combat-Related Trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2023 Sep 21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.22.01284. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37733907.