LOS ANGELES — Racial health disparities in the United States are well documented, but the starkest are with reproductive health and outcomes, according to a VA researcher.

Jodie G. Katon, PhD, an investigator at the VA Greater Los Angeles’ Center for the Study of Health Care Innovation, Implementation and Policy, advised, “For example, black, African American and indigenous pregnant and birthing people have roughly 2-3 times higher risk of mortality than their white peers. These racial disparities persist regardless of education or income level.”

What hasn’t been well documented is whether the same types of disparities that have been documented outside the VHA are present among veterans, said Katon, Because of the increased use of VA pregnancy benefits and the growing percentage of women and gender-diverse veterans—many of whom identify as Black or African American—Katon and her colleagues thought it was important to find out.

The study team sought answers by going straight to the source—veterans who had a VA-paid birth provided through community care. All veterans who had a VA-paid live birth between June 2018 and December 2019 were identified through VA records and sent a survey, which was modeled after one used by biannually by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to broadly monitor pregnancy health behaviors and outcomes in the United States.

Veterans were able to complete the survey online or by phone. “The online component was actually set up so that they could do It on a telephone, so that made participation easier, and we think it increased our response rate,” Katon said.

The analytic sample consisted of 1,220 veterans—916 Black and 304 white—representing 3,439 weighted responses.

A key finding of the study, reported in the Journal of Women’s Health, was that it did not detect any racial disparities in terms of access to pregnancy—an important, positive and “somewhat surprising” finding, Katon said.1

“The failure to detect a statistically significant difference by race in access to and use of health care during the perinatal period is consistent with prior literature indicating that for many process measures, racial disparities observed outside VA are reduced or eliminated within VA,” Katon and her colleagues wrote. “In fact, our estimates indicate that timely prenatal care was more frequent among veterans using VA pregnancy benefits than among the general population, both overall and by race.”

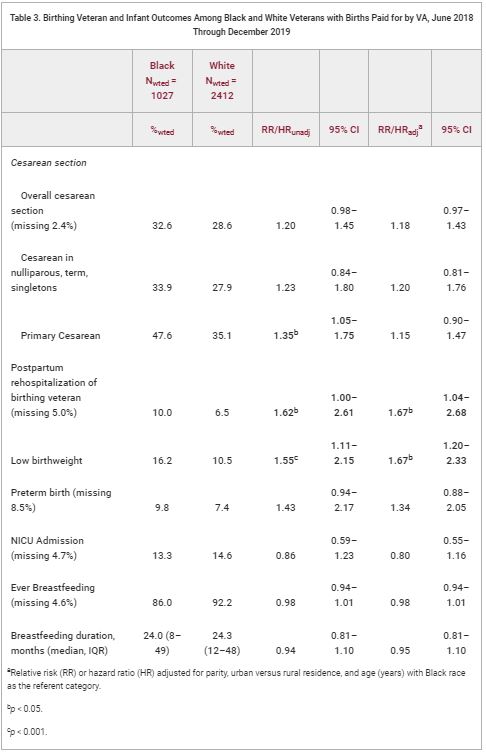

Unfortunately, however, it did detect racial disparities in some outcomes for veterans and their infants, Katon said. “Specifically, we found Black veterans were more likely than white veterans to have low birth weight infants, and they were also more likely to report being hospitalized in the 12 months after giving birth,” she said. “It is hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison with the general population, but those disparities have been reported for nonveteran populations in the U.S.”

The study wasn’t designed to explain why such disparities existed—only that they did. “First we needed to document that it existed,” she said.

Structural Racism

In terms of an explanation, Katon said she can only hypothesize. “But there has been a substantial amount of research outside of VA that really highlights the role of structural and interpersonal racism and how these drive inequities in terms of social determinants of health—things such as access to housing, nutritious foods, jobs, education, all of that stuff that is about where we live, work and play—and then how this in turn drives racial disparities and pregnancy outcomes,” she said. “We could hypothesize that the same forces are at work in our veteran population. Now that we have these numbers, now that we have done the very descriptive work, our future goal is to conduct research to explore how these factors specifically impact veterans and to learn if there are key differences for veterans versus non-veterans with the goal of ultimately informing VA pregnancy care-related policies and programs to really ensure health equity and optimal outcomes for all veterans.”

A wide range of work outside the VA has been aimed to eliminating racial disparities in pregnancy outcomes, said Katon. Most has focused on community-based approaches such as expanding access to doulas—individuals who are trained to provide continuous support during pregnancy childbirth and postpartum—having the availability of community-based midwifery, and looking at ways to diversity the pregnancy workforce in terms of race and ethnicity and training so that teams with different backgrounds are caring for people. There is also some promising data on alternate models of care such as group prenatal care as well as payment and delivery system reform, she said.

“There are some challenges in terms of how VA can ensure access for veterans or enhance access to these services, but the hope would be to find ways they can work in programs and policies that would enhance access – specifically to these types of care,” Katon said. “Because the big take home is that simply providing access to prenatal care, labor and delivery care, is really not sufficient to eliminate racial disparities in outcomes.”

Even though VA clinicians in primary care and gynecology do not provide pregnancy care directly (nearly all veteran perinatal care is purchased by VA from non-VA community providers), they can make a difference both through advocating for policy and program changes and their interactions with patients, Katon said.

“They do have opportunities, both pre-pregnancy and post-pregnancy, to really help veterans optimize their health, but this has to be done in a culturally competent manner that avoids some of these narratives that we see around patient shame and blame,” Katon said. “But I do think there is a real role for VA and specifically VA primary care in that role to reduce or eliminate the racial disparities that we observed in addition to the maternity care coordination, whose role starts at the time of pregnancy and continues post-partum.”

- Katon JG, Bossick AS, Tartaglione EV, Enquobahrie DA, Haeger KO, Johnson AM, Ma EW, Savitz D, Shaw JG, Todd-Stenberg J, Yano EM, Washington DL, Christy AY. Assessing Racial Disparities in Access, Use, and Outcomes for Pregnant and Postpartum Veterans and Their Infants in Veterans Health Administration. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2023 May 15. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2022.0507. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37186805.