PEMBROKE, NC — Explosive blasts account for a majority of the injuries among wounded servicemembers, but some of the most long-term and damaging effects of blast exposure might be slipping by undetected.

Over the past decade, research into the neurological effects of blast exposure experienced by servicemembers has revealed that even individuals without traditional markers of brain injury can experience cognitive impairment resulting from their exposure.

“Blasts can lead to debilitating neurological and psychological damage, but the underlying injury mechanisms are not well understood,” said Frederick Gregory, PhD, program manager, neurophysiology of cognition, Army Combat Capabilities Development Command (DEVCOM) Army Research Laboratory, Army Research Organization, Research Triangle Park, NC. “[T]he molecular pathophysiology of blast-induced brain injury and potential impacts on long-term brain health is extremely important to understand in order to protect the lifelong health and well-being of our service members.”

At a minimum, the 430,000 servicemembers who experienced traumatic brain injury (TBI) between 2000 and 2020 face a risk of ongoing neurological damage. With greater understanding of blast-related neurological effects in those never diagnosed with TBI, the number affected could be much larger—creating a significant challenge for the VA for decades to come.

Recent evidence indicates that a servicemember’s distance from the blast more accurately predicts later cognitive impairment than their TBI status or concussion symptoms, with one of the main effects of blast exposure being problems with memory retrieval.1,2 For some, those memory retrieval issues persist and become a chronic impairment. Blast-related neurological complications also may lead to dementia, as even servicemembers with only mild TBI and no loss of consciousness are at greater risk for developing dementia later in life than those without blast exposure.3

Already, signs have begun to accumulate that many more individuals sustained damage from blasts than the TBI numbers suggest. Gregory’s colleagues at the Army Research Laboratory in collaboration with Ben Bahr, PhD, William C. Friday, chair and professor at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, and scientists at the National Institutes of Health discovered an “alarming numbers of blast‐exposed individuals returning from war zones with no detectable physical injury or neuropathology but who still suffer from persistent neurological symptoms including depression, headaches, anxiety, irritability, sleep disturbances, blurred vision and memory problems.”4

Biomarkers for Blast Damage?

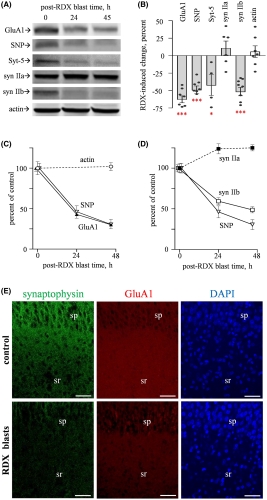

Significantly, the blast-induced alterations included reductions in protein levels and electrical activity, rather than the more easily detectable neurological shifts such as neuronal loss, morphological alterations or changes in resting membrane potential. “This finding may explain those many blast-exposed individuals returning from war zones with no detectable brain injury but who still suffer from persistent neurological symptoms, including depression, headaches, irritability and memory problems,” explained co-author Ben Bahr, PhD, William C. Friday chair and professor at UNC Pembroke.

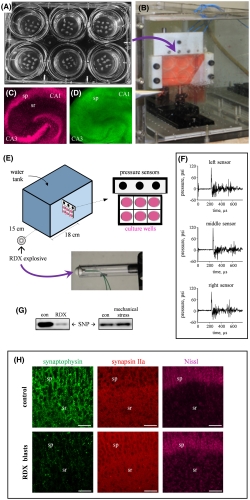

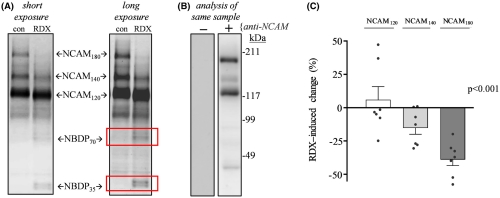

Specifically, the researchers noted significant blast‐induced reductions in synaptophysin, synapsin isoform IIb, synaptotagmin‐5, in the AMPA‐type glutamate receptor subunit GluA1, and in the post-synaptic neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM180, as well as reduced evoked post-synaptic current amplitude. Many of these molecules, such as NCAM180, synaptophysin, synapsin IIb, synaptotagmin, and GluA1, are also reduced in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, strengthening the link between blast exposure and dementia found in previous studies.

The connection to Alzheimer’s makes these results even more important. “The need for early biomarkers of blast injuries cannot be stressed enough in order to identify those initial neuronal alterations that may tip the scales toward dementia,” the authors concluded.

The consistent reductions in protein levels and post-synaptic current amplitude in blast-exposed tissue demonstrated a direct

effect on brain function, even when that effect is not reflected by tissue damage or loss. The study offers a physiological explanation for the correlation between blast exposure and cognitive impairment found in previous studies and a direction for future research.

The discovery of the hidden effects of blasts could transform care for veterans and add significantly to the understanding of dementia. According to Bahr, “[e]arly detection of this measurable deterioration could improve diagnoses and treatment of recurring neuropsychiatric impediments and reduce the risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease later in life.”

- Robinson ME, Lindemer ER, Fonda JR, Milberg WP, McGlinchey RE, Salat DH. Close-range blast exposure is associated with altered functional connectivity in veterans independent of concussion symptoms at time of exposure. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015 Mar;36(3):911-22.

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, Levin LK, Fortier CB, Milberg WP, McGlinchey RE. Verbal Memory Deficits in OEF/OIF/OND Veterans Exposed to Blasts at Close Range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018 Jan 24:1-10.

- Barnes DE, Byers AL, Gardner RC, Seal KH, Boscardin WJ, Yaffe K. Association of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury With and Without Loss of Consciousness With Dementia in US Military Veterans. JAMA Neurol. 2018 May 7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0815. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 29801145.

- Almeida MF, Piehler T, Carstens KE, Zhao M, Samadi M, Dudek SM, Norton CJ, Parisian CM, Farizatto KLG, Bahr BA. Distinct and dementia-related synaptopathy in the hippocampus after military blast exposures. Brain Pathol. 2021 Feb 24:e12936. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12936. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33629462.