Small Risk Not Linked to Greater Mortality, However

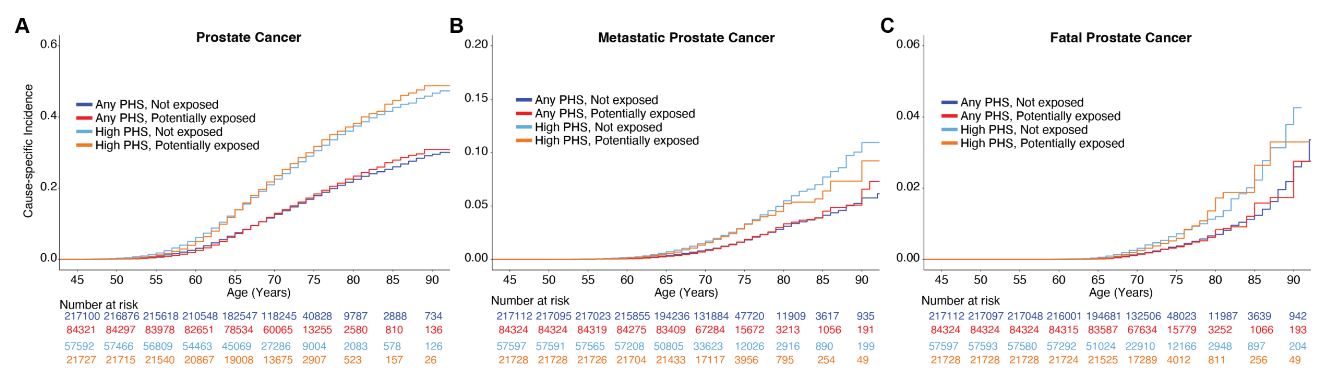

Click to Enlarge: Million Veteran Program (MVP) cause-specific cumulative incidence based on Agent Orange exposure for participants with high(top 20%)genetic risk of prostate cancer. Cause-specific cumulative incidence among MVP participants on active duty during the Vietnam War, stratified by Agent Orange exposure and PHS290 for (A) all prostate cancer, (B) metastatic prostate cancer, and (C) fatal prostate cancer. ‘High PHS290’ indicates participants with PHS in the top 20% of genetic risk, as assessed by PHS290, a polygenic hazard score Source: Acta Oncologica

SAN DIEGO — In veterans who were on active duty during the Vietnam War era, exposure to Agent Orange was associated with a small increase in the risk of developing prostate cancer, but not metastatic prostate cancer or fatal prostate cancer, according to a recent study.

The study published in Acta Oncologica assessed whether Agent Orange exposure was associated with a heightened of any metastatic or fatal prostate cancer in a diverse veteran cohort. It involved researchers from the VA San Diego Healthcare System, VA Salt Lake City (UT) Healthcare System and VA Boston Healthcare System.1

Agent Orange, defined as “a mixture of herbicides 2,4-dichlorophenoxy-acetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T), kerosene and diesel fuel, was used in the Vietnam War to clear dense vegetation and destroy food crops.” The U.S. government “considers veterans to have been exposed to Agent Orange if they served in Vietnam while the carcinogen was in use,” according to the study authors, who added that veterans exposed to Agent Orange are considered to be at high risk of prostate cancer.

This study involved 301,470 participants who were identified from the Million Veteran Program, a population-based cohort that started enrollment in 2011 with genotyping, long-term follow-up, and linked clinical records for more than 870,000 participating U.S. veterans.

For this study, participants were on active duty during the Vietnam War era (August 1964 to April 1975) and exposed to Agent Orange based on the DoD’s definition. The median age at prostate cancer diagnosis was 65.3 years, and the median age at last follow-up was 71.3 years. The study assessed genetic risk and associations with age at diagnosis of any prostate cancer, metastatic prostate cancer and death from prostate cancer, according to the authors.

“We found that Agent Orange exposure was possibly associated with a very small increase in risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer, but veterans exposed to Agent Orange were not more likely to have metastatic or fatal prostate cancer,” co-author Tyler Seibert, MD, PhD, a researcher at the VA San Diego Healthcare System, told U.S. Medicine.

Not More Aggressive

“In other words, veterans who served during Vietnam are not more likely to have aggressive prostate cancer if they served in Vietnam vs. if they served elsewhere,” said Seibert, who also is a radiation oncologist and assistant professor at University of California, San Diego. “These findings appeared to be independent of race/ethnicity, family history and genetic risk. It is important to note that “Agent Orange exposure” was determined using the government definition of exposure, basically being that they were physically in Vietnam when Agent Orange was in use. We do not know how much Agent Orange each individual in the study was exposed to (nor do we typically have that information when we care for patients in clinic).”

Some veterans who served in Vietnam while Agent Orange was in use “may have had heavy and/or frequent exposure, while others may have escaped with little to no exposure,” the authors pointed out. “It’s possible that intense Agent Orange exposure is associated with aggressive prostate cancer, but adequate data will likely never be available to answer this question. This study used the same definition of Agent Orange exposure that is used by the VA Compensation & Pension Committee to address the needs of potentially exposed individuals, which estimates associations of the average exposure by those veterans serving in Vietnam during use of Agent Orange.”

To their knowledge, the authors reported that their study as the “largest study to explore whether veterans exposed to Agent Orange are at significantly higher risk of prostate cancer and the only study to account for family history, race, ethnicity, genetic ancestry and genetic risk.”

“There has long been a belief that veterans exposed (or potentially exposed) to Agent Orange were at significantly higher risk of prostate cancer,” Seibert said. “For the typical patient, history of Agent Orange exposure should not be a factor in decision-making around prostate cancer screening, diagnosis or treatment.”

Looking specifically at veterans surviving to 2011 or later, the authors concluded that average Agent Orange exposure among those serving during the Vietnam War era has a much smaller effect size than do family history, Black race or high polygenic risk.

The study’s findings “may have pragmatic implications for early detection strategies and suggest the U.S. definition of Agent Orange exposure does not substantially increase risk of morbidity or mortality from prostate cancer, at least for individuals alive today. The study also helps inform inclusion criteria for clinical trial enrollment in the VA and sets the foundation to better understand veteran exposures such as burn pits that need to be monitored,” the authors suggested.

However, the authors noted that “effects may be underestimated because the study focused on veterans who were alive for A Million Veteran Program enrollment in 2011 and did not include veterans who may have died prior to 2011 from Agent Orange exposure effects.”

- Pagadala MS, Lui AJ, Zhong AY, Lynch JA, et.al. Agent orange exposure and prostate cancer risk in the million veteran program. Acta Oncol. 2024 May 23;63:373-378. doi: 10.2340/1651-226X.2024.25053. PMID: 38779869.