Pneumonia Diagnosis in Veterans, Either Incorrect or Initially Missed

Barbara Jones, MD, MSCI, Pulmonary and Critical Care Physician at University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City

SALT LAKE CITY — Pneumonia diagnoses change more often than not at VA hospitals, either because a veteran initially thought to have the infection is diagnosed with something else or because the community-acquired pneumonia diagnosis was missed when the patient entered the hospital.

That’s according to a study in Annals of Internal Medicine based on an AI-based analysis of more than 2 million VAMC visits.1

“Pneumonia can seem like a clear-cut diagnosis,” advised lead author Barbara Jones, MD, MSCI, pulmonary and critical care physician at University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, “but there is actually quite a bit of overlap with other diagnoses that can mimic pneumonia.”

The study determined that a third of patients who were ultimately diagnosed with pneumonia had not received that diagnosis when they entered the hospital. At the same time, nearly 40% of initial pneumonia diagnoses were later revised.

The researchers reached those conclusions by searching medical records from more than 100 VAMCs across the country, using artificial intelligence-based tools to identify mismatches between initial diagnoses and diagnoses upon discharge from the hospital.

“Evidence-based practice in community-acquired pneumonia often assumes an accurate initial diagnosis,” the authors wrote, explaining why they sought to examine the evolution of pneumonia diagnoses among patients hospitalized from the emergency department (ED).

The retrospective nationwide cohort study involved 118 U.S. Veterans Affairs medical centers and nearly 2.4 million hospitalizations. Included were records from veterans admitted from the ED between Jan. 1, 2015, and Jan. 31, 2022.

The study team identified discordances between initial pneumonia diagnosis, discharge diagnosis and radiographic diagnosis using natural language processing of clinician text, diagnostic coding, and antimicrobial treatment. Comparisons were made of expressions of uncertainty in clinical notes, patient illness severity, treatments and outcomes.

Results indicated that 13.3% of the patients received an initial or discharge diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia—9.1% received an initial diagnosis and 10.0% received a discharge diagnosis. “Discordances between initial and discharge occurred in 57%,” the authors wrote.

“Among patients discharged with a pneumonia diagnosis and positive initial chest image, 33% lacked an initial diagnosis,” they added. “Among patients diagnosed initially, 36% lacked a discharge diagnosis and 21% lacked positive initial chest imaging. Uncertainty was frequently expressed in clinical notes (58% in ED; 48% at discharge); 27% received diuretics, 36% received corticosteroids, and 10% received antibiotics, corticosteroids, and diuretics within 24 hours.

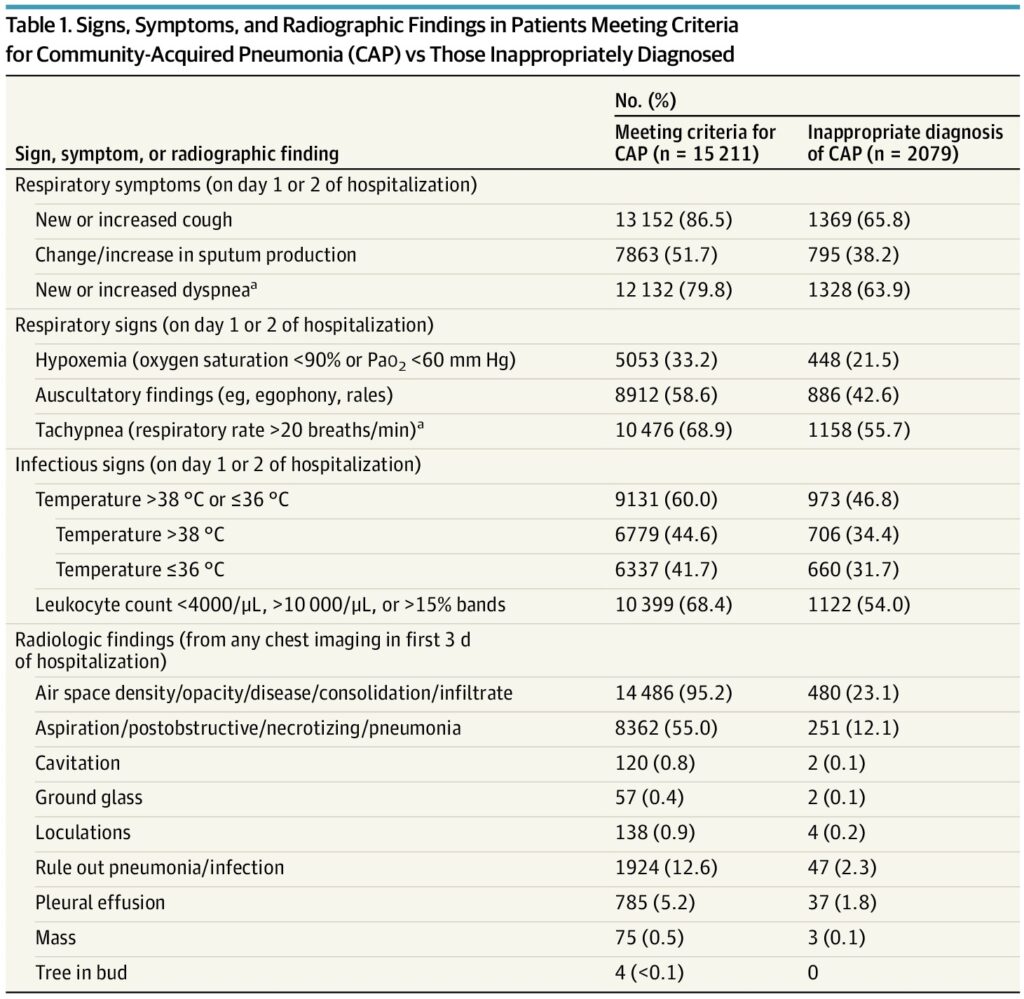

Click to Enlarge: Signs, Symptoms, and Radiographic Findings in Patients Meeting Criteria for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) vs Those Inappropriately Diagnosed Abbreviation: Pao2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen.

SI conversion factors: To convert Pao2 to kilopascals, multiply by 0.133; leukocytes to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001.

a. The presence of either new or increased dyspnea or tachypnea qualifies as a single sign or symptom of CAP. Source: JAMA Network Open

Simultaneous treatments for multiple potential diagnoses were also common, according to the article. While patients with discordant diagnoses had greater uncertainty and received more additional treatments, only patients lacking an initial pneumonia diagnosis had higher 30-day mortality than concordant patients (14.4% [95% CI, 14.1% to 14.7%] vs. 10.6% [CI, 10.4% to 10.7%]), according to the report.

High-Complexity Facilities Involved

“Patients with diagnostic discordance were more likely to present to high-complexity facilities with high ED patient load and inpatient census,” the researchers pointed out.

“More than half of all patients hospitalized and treated for pneumonia had discordant diagnoses from initial presentation to discharge. Treatments for other diagnoses and expressions of uncertainty were common,” the study concluded. “These findings highlight the need to recognize diagnostic uncertainty and treatment ambiguity in research and practice of pneumonia-related care.”

The authors suggested that their results challenge existing research on pneumonia treatment, which operates on the assumption that initial and discharge diagnoses will be the same.

Jones recommended that a high level of uncertainty should be maintained after an initial pneumonia diagnosis, and that VA clinicians be willing to adapt to new information throughout the treatment process.

“Both patients and clinicians need to pay attention to their recovery and question the diagnosis if they don’t get better with treatment,” she suggested.

The issue is not limited to VA facilities, however, although the situation might be worse in the VHA. A study published a few months ago in JAMA Internal Medicine pointed to similar issues in 48 Michigan hospitals.2

Researchers from the VA Ann Arbor, MI, Healthcare System and the University of Michigan Medical School questioned the incidence of and factors associated with inappropriate diagnoses among hospitalized patients diagnosed with pneumonia.

In the cohort study of 17,290 hospitalized adults treated for pneumonia in 48 Michigan hospitals, 12.0% were found to be inappropriately diagnosed. The researchers suggested that older patients, those with dementia and those presenting with altered mental status had the highest risk of being inappropriately diagnosed. For those inappropriately diagnosed, receiving a full antibiotic duration was associated with antibiotic-associated adverse events.

“Inappropriate diagnosis of pneumonia among hospitalized adults is common, particularly among older adults with geriatric syndromes, and may be harmful,” the authors pointed out.

Based on medical record review and patient telephone calls, the study took place between July 1, 2017, and March 31, 2020. Trained abstractors retrospectively assessed hospitalized patients treated for CAP between July 1, 2017, and March 31, 2020. All patients received antibiotics on day 1 or 2 of hospitalization.

“In this cohort study, inappropriate diagnosis of CAP among hospitalized adults was common, particularly among older adults, those with dementia, and those presenting with altered mental status. Full-course antibiotic treatment of those inappropriately diagnosed with CAP may be harmful,” the authors wrote.

Background information in that study noted that lower respiratory tract infection, including community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), is the fourth-most-common cause of medical hospitalization and most common infectious cause of hospitalization in the United States.

“While some inappropriate diagnosis of CAP is unavoidable due to diagnostic uncertainty when patients are first hospitalized, many patients remain inappropriately diagnosed even on hospital discharge,” the researchers advised. “Inappropriate diagnosis of CAP may harm patients through delayed recognition and treatment of acute (e.g., exacerbations of congestive heart failure), chronic (e.g., pulmonary cancer), or novel diagnoses (e.g., pulmonary cancer) and may lead to unnecessary antibiotic use, adverse effects, and antibiotic resistance.”

- Jones BE, Chapman AB, Ying J, Rutter ED, et. Al. Diagnostic Discordance, Uncertainty, and Treatment Ambiguity in Community-Acquired Pneumonia : A National Cohort Study of 115 U.S. Veterans Affairs Hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2024 Aug 6. doi: 10.7326/M23-2505. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39102729.

- Gupta AB, Flanders SA, Petty LA, Gandhi TN, et. Al. Inappropriate Diagnosis of Pneumonia Among Hospitalized Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2024 May 1;184(5):548-556. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.0077. PMID: 38526476; PMCID: PMC10964165.