SEATTLE—New guidelines published in 2017 upended recommendations for use of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary. Two years later, many VA patients still receive discordant care.

To fix the problem, the VA’s Health Services Research and Development group has developed a process that addresses physician and patient concerns related to reducing ICS use and recently made it available as a toolkit for others to follow.

The 2017 Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines limited the use of inhaled corticosteroids to patients at high risk for future exacerbations. At the same time, the recommendations changed the definition of high risk to include only patients who had two or more outpatient exacerbations or at least one exacerbation requiring hospitalization in the previous year. Earlier recommendations also had included patients with airflow limitation based on indications of obstruction with spirometry.

While many physicians and patients have become comfortable with using inhaled corticosteroids to treat COPD, the GOLD panel found that the harms associated with ICS often outweighed the benefits.

A “re-review of older literature in conjunction with newer research studies demonstrated increased risk of pneumonia and other potential harms associated with inhaled corticosteroid use. At the same time, the committee noted that the benefits of ICS in symptom and COPD exacerbation risk could be achieved through single or dual use of long acting bronchodilators, without the associated risk of pneumonia,” explained David H. Au, MD, MSc, director of the VA Health Services Research and Development Denver-Seattle Center of Innovation for Veteran-Centered and Value-Driven Care located at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle.

The Risk to Veterans

On average, 1 in 62 patients on ICS will develop pneumonia, according to the VA. Inhaled corticosteroids also increase the risk of cataracts and bone fractures and are associated with poor diabetes control.

A large study of COPD patients found that ICS use increases the risk of serious pneumonia—illness so severe that it requires hospitalization or leads to death—by 69%. The increased risk drops immediately on discontinuation and vanishes within six months.1 An earlier study calculated that the highest dose of ICS (fluticasone 1000 µg per day or more) increased the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia followed by death within 30 days by 80%.2

About one million veterans have a diagnosis of COPD, and 40% of them currently use inhaled corticosteroids, according to a letter to the editor of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine written by Seppo T. Rinne, MD, PhD, an investigator in the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford, MA, and assistant professor of medicine at the Boston University School of Medicine, and VA colleagues.3

That means nearly 6,500 veterans have an increased risk of pneumonia as a result of ICS therapy.

Rinne and his colleagues determined that more than 90% of prescriptions for ICS therapy in the VA did not conform to current guidelines and that 27% were not warranted under the previous guidelines. Their study evaluated ICS use in 42,478 veterans who had a diagnosis of COPD and airflow obstruction as determined by pulmonary function tests.

“There are multiple reasons that ICS are overprescribed,” according to Renda S. Wiener, MD, MPH, acting associate director of the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research at the Bedford VA and associate professor of medicine at Boston University Medical School.

Much of the overprescription can be attributed to habit and fear, she told U.S. Medicine. Inhaled corticosteroids “were adopted in clinical practice before other current therapies and changing therapies that patients may have been taking is difficult for providers and patients. COPD also can be extremely challenging disease to treat. Patients and providers often search for any therapy that may improve symptoms, and many people mistakenly think that more inhaler therapies will help their quality of life.”

Program Tackles Overprescription

To address the high rate of ICS overprescription, VA’s Quality and Safety National Quality Enhancement Research Initiative program tested a pulmonary specialist-initiated consultation.

The program started at 13 VA community-based outpatient clinics in New England and the Pacific Northwest, according to a study published in the January 2019 issue of VA’s online publication about QUERI research, Veterans’ Perspectives.

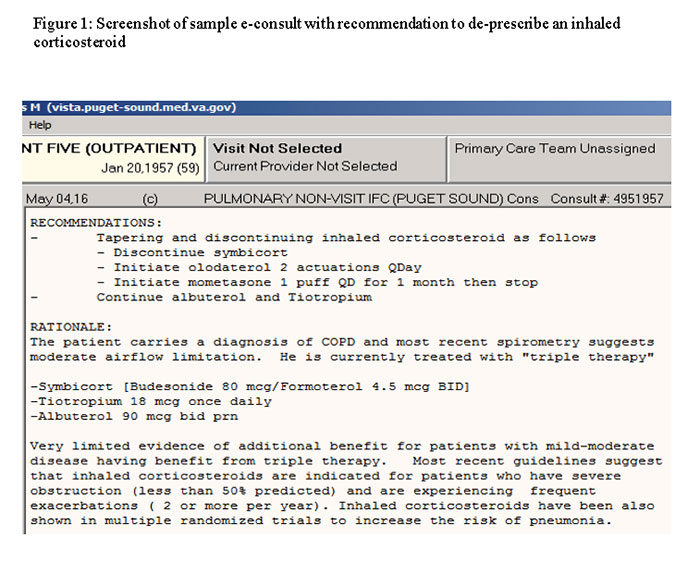

As part of the program, instead of waiting for a referral from primary care, a pulmonary specialty team proactively searches the electronic health record to identify veterans with COPD who have an upcoming appointment and are on ICS therapy. If the team does not find a reason for the prescription, such as frequent exacerbations in the past year or concurrent asthma, they add a note to the patient record recommending a change, such as tapering and discontinuing ICS or performing a pulmonary function test to verify that the shortness of breath is a result of COPD and not another common cause, such as heart failure.

Program developers worried that primary care physicians would ignore or dislike receiving the electronic messages. Discussions with providers before the team began sending the notes found misgivings about making a prescription change, both because of expected patient pushback and because of their own concerns about increased exacerbations without ICS.

Once the messages started, however, the provider response changed.

“We have been pleasantly surprised by how positively providers responded to the proactive e-consults. Providers receive a lot of reminders and notifications, and we were concerned about creating more burden,” said Laura Feemster, MD, MS, core investigator for the Denver-Seattle COIN for Veteran-Centered and Value-Driven Care and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“We directly asked providers, and they generally described the proactive electronic consults as helpful,” Feemster told U.S. Medicine. “In one interview, one provider told us, “I think in a busy primary care practice, where we have to remember a lot of different things, it’s really helpful to have things like this, where somebody is watching over our shoulders.”

While the majority of providers who received messages from the pulmonary specialty team chose to discuss tapering ICS with their patients, 46% of providers did not. Those who did not might find comfort in the finding that 90% of primary care providers who initiated conversations about ICS therapy reported that their patients were open to discontinuing the therapy.

And the patients generally do well when ICS therapy stops. “On aggregate, patients who do not meet guideline criteria for ICS use are able to tolerate discontinuation of these medications without worsening of their COPD control,” Wiener said. “The proactive e-consult with pulmonologist review helps ensure that we are selecting appropriate candidates for ICS discontinuation, rather than clinically unstable patients who are poor candidates for ICS discontinuation.”

The researchers are developing an implementation toolkit to help other VAMCs adopt the program, which they plan to disseminate in conjunction with the VA’s Office of Specialty Care and the national program director for Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine. “The toolkit will reflect our experience with de-escalating use of ICS and contain instructions and standard operating procedures for reviewing cases,” said Christian Helfrich, PhD, core investigator with the Denver-Seattle COIN for Veteran-Centered and Value-Driven Care and research associate professor at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Just the surveys and interviews for the program appear to have increased provider awareness of the risks of ICS and the new guidelines for use, Helfrich told U.S. Medicine. One “provider who received the intervention told us, “I don’t think I would’ve necessarily picked up on the fact that he shouldn’t have been on an inhaled steroid. But because of the project and the survey, it’s come to my awareness more.”

Suissa S, Patenaude V, Lapi F, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumonia. Thorax. 2013 Nov;68(11):1029-36.

Ernst P, Gonzalez AV, Brassard P, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroid use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Jul 15;176(2):162-6.

Rinne ST, Wiener RS, Chen Y, Rise P, Udris E, Feemster LC, Au DH. Impact of Guideline Changes on Indications for Inhaled Corticosteroids among Veterans with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018 Nov 1;198(9):1226-1228.