SEATTLE — Exposure to oil well fires, burn pits and sand and dust particles as well as the use of tobacco products puts veterans at increased risk of lung diseases, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). While exacerbations of COPD are potentially life-threatening, studies have shown that most people discharged after an exacerbation of COPD do not receive care known to improve outcomes.

Researchers at the University of Washington and VA Puget Sound Health System in Seattle are working to change that through an intervention collaborating with primary care providers.

As a pulmonologist with the VA Puget Sound Health System, Laura Spece, MD, MS, found that patients needing to see her or one of her colleagues often had difficulty doing so due to distance or long appointment factors wait times.

“It became clear that some of the care for COPD could really be improved by collaborating with primary care providers, who tend to be closer and have more convenient schedules for veterans with COPD,” she said. “We wanted to see how we could extend the reach of the pulmonary specialists to ensure folks get the care they need.”

For the intervention—INtegrating Care After Exacerbation of COPD (InCasE) —study clinicians, consisting of experienced primary care providers and pulmonary specialists, reviewed medical records for patients discharged from the hospital for COPD. For each patient, the team looked for gaps in care for COPD and key comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. They focused on immediate-care processes associated with the hospital admission and comorbid disease treatment. For providers in the intervention group, the team placed any patient care recommendations into the medical record using a nonvisit consult note and prefilled order sets. The patient’s provider then accepted, modified, or declined any or all of the recommendations based on personal knowledge of the patient’s history.

A clinical trial, which tested the intervention at two VHA health care systems and 10 community-based outpatient clinics for a period of 30 months beginning May 2015, yielded positive results. PCPs in the intervention arm adopted most recommendations by the study team (77.3%) and patients reported improved symptom control and quality of life, based on Clinical COPD Questionnaire scores.!

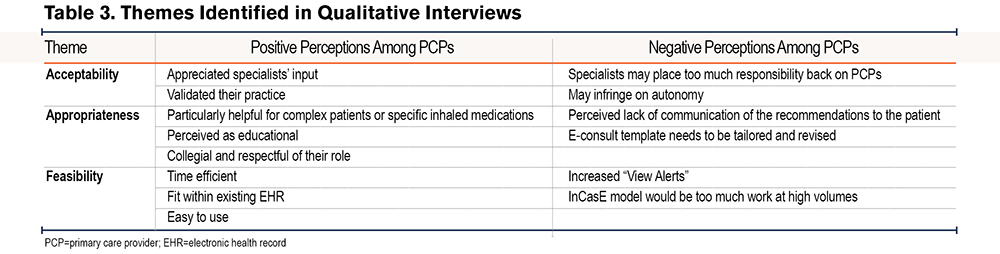

While the trial examined the benefits of the intervention, researchers were also concerned about primary care providers’ response to it—particularly whether they found the COPD follow-up burdensome. In a simultaneous study published in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases, Spece and her colleagues went directly to the providers for answers. “We asked primary care providers what they thought of the study and the intervention so we could understand how to make it more usable for them given how busy they are,” she told U.S. Medicine.

Surveys were administered by email and email to 139 PCPs in the intervention arm between August 2015 and December 2017. PCPs received a survey invitation one week after initial exposure to the intervention. The researchers also reached out by email to PCPs asking if they would be willing to commit to a 45-minute to one-hour interview, Spece said. “We wanted this to work, and we really don’t want to be burdensome to primary care physicians. We really want to know what they think.”

Positive Findings

The findings, she said, were for the most part positive. “We found that PCPs generally liked it,” she said. “They liked having a pulmonary team take more of a proactive approach to consulting patients instead of waiting to be asked. They liked that we tried to put in orders for them to help them out—like ordering the appropriate test or help with the dosing of medication.”

While some did comment that it could be a challenge to receive too many of these because it did generate more work for them, overall they thought it was worth it, Spece said. “They also thought that the way we approached communicating the recommendations to them was very collegial and respectful.”

Based on the survey responses, she says the researchers are still trying to straighten out some issues such as how they can better support primary care and how to make sure the veteran knows their recommendations have been seen by a pulmonologist and tailored to their unique case in an effort to save them time and resources.

While research has shown “probably only 30% of referrals to specialty medicine end up being complete,” Spece says, she hopes the InCasE intervention will bring this closer to 100% for patients needing follow-up for COPD.

Further, the studies’ findings suggest that InCasE could provide a transferable care delivery model for other chronic diseases to improve patient outcomes, support primary care and provide access to specialty care.

“Specialty medicine can improve access to high quality care using a population health approach in collaboration with primary care,” the authors wrote. “InCasE provides an opportunity to redesign consultation with specialty medicine in a way that is acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to primary care. Further work will need to test how InCasE could be adapted to other clinical scenarios.”

- Au DH, Collins MP, Berger DB, Carvalho PG, et. al. Health System Approach to Improve Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Care after Hospital Discharge: Stepped-Wedge Clinical Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Jun 1;205(11):1281-1289. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202107-1707OC. PMID: 35333140.

- Spece LJ, Weppner WG, Weiner BJ, Collins M, et. al. Primary Care Provider Experience With Proactive E-Consults to Improve COPD Outcomes and Access to Specialty Care. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2023 Jan 25;10(1):46-54. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2022.0357. PMID: 36472622.