SAN DIEGO — Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression are common mental health conditions among U.S. servicemembers, yet only a fraction of those affected pursue mental healthcare services. An even smaller proportion receive adequate levels of care.

This gap in care can have serious negative implications for both the health and operational readiness of servicemembers, stated the authors of a new study that sought to understand the factors linked to mental healthcare utilization.

“The unique aspects of the U.S. military healthcare system (e.g., no cost for medical care, mental health notes may be available to superiors) may provide contrasting pressure to seek or not seek mental health services,” the researchers wrote in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. “Identifying specific factors that influence utilization of mental healthcare may inform future interventions aimed at improving long-term mental health and readiness in military populations.”1

Unlike earlier studies that focused primarily on administrative records or veteran samples who had already sought mental healthcare, this new study aimed to investigate mental healthcare utilization among a contemporary sample of active military personnel from all service components and branches. This approach might offer unique insights into whether specific subpopulations face a higher risk of unmet mental health needs.

The researchers, led by Neika Sharifian, PhD, a research Scientist at the Naval Health Research Center Leidos in San Diego, analyzed cross-sectional data from the 2019-2021 survey assessment of the Millennium Cohort Study, the largest and longest running prospective cohort study of U.S. servicemembers and veterans. Between 2001-2021, five separate cohorts of servicemembers were randomly selected from active military rosters from all service branches and components to enroll.

To assess unmet mental healthcare needs, they restricted the current study population to servicemembers who had met criteria for subthreshold or probable PTSD and/or depression. All mental health conditions were identified using self-reported screening tools.

Mental healthcare utilization for PTSD and depression were evaluated separately. Participants were asked to report the total number of therapy sessions (both group and individual) they had attended in the past 12 months and whether they were taking medication for each condition. To assess the adequacy of care, the researcher defined minimally adequate care as receiving eight or more therapy sessions for PTSD and/or depression. Participants were considered to have positive medication use if they reported taking medication for either PTSD or depression.

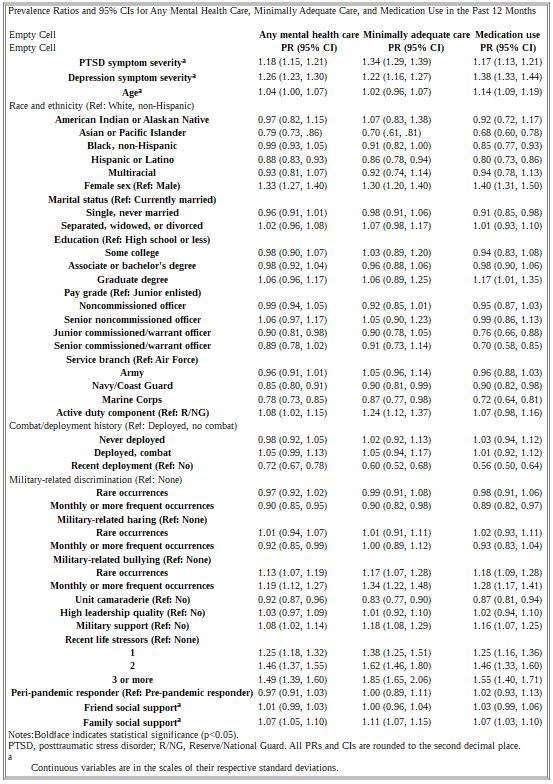

The researchers also assessed a wide range of socioeconomic, military and psychosocial factors—including education, marital status, age, race, ethnicity, sex, military support, discrimination, hazing, bullying, social support and life stressors—using self-reported surveys and Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory.

Of 18,420 participants in the final analytic sample, 51% met subthreshold criteria, while the remaining 49% met threshold criteria; 31.7% reported receiving any mental healthcare: 15.6% reported minimally adequate care; and 18.6% reported medication use. Additionally, 10.7% reported both minimally adequate care and medication use.

Who Uses Services?

After adjustments, factors linked to a higher likelihood of reporting each mental healthcare utilization metric included greater PTSD severity, greater depression severity, female sex (compared to male), military-related bullying, military social support, experiencing one or more life stressors and family social support. Additionally, gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals were more likely to report mental healthcare use compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Conversely, factors associated with a lower likelihood of reporting each mental healthcare utilization metric included being of Asian or Pacific Islander or Hispanic race and ethnicity (compared to non-Hispanic white), serving in the Navy/Coast Guard or Marine Corps (compared to the Air Force), experiencing monthly or more frequent military-related discrimination, recent deployment and a strong sense of unit camaraderie. Monthly experiences of military-related hazing also were associated with a lower likelihood of reporting any mental healthcare use.

Groups less likely to report medication use included non-Hispanic black individuals (compared to white individuals), single individuals (compared to married peers) and junior and senior commissioned or warrant officers (compared to junior enlisted personnel). On the other hand, those with a graduate degree were more likely to report medication use compared to those with a high school education or less.

Active-duty servicemembers reported higher rates of any mental healthcare and minimally adequate care compared to those in the Reserves or National Guard. Among participants who screened positive for probable PTSD and/or depression, the percentage reporting mental healthcare utilization was higher, with 42.5% reporting any care, 22.6% receiving minimally adequate care, and 26.0% using medication.

The authors stated the disparities may be due, in part, to myriad cultural and structural barriers that limit access to and use of behavioral health services in the military. “Notably, a shortage of behavioral healthcare providers, pervasive stigma around mental health needs, extended wait times for specialty care, and lack of culturally competent care may be a few examples of barriers to care and potential actionable points of intervention,” they wrote.

They noted that the DoD has recognized many of these barriers and recommendations have been made, such as expediting the hiring process for behavioral health professionals, optimizing telehealth options and increasing the number of active-duty behavioral health technicians, to improve mental health services for military personnel. “For example, the expansion of telehealth behavioral health services—when implemented with cultural sensitivity—may help to mitigate some of these unmet mental health needs,” the authors advised.

The findings, they concluded, “highlight a need for a better understanding of factors associated with mental healthcare utilization in order to target future interventions, programs, and strategies to increase mental healthcare treatment among those with unmet mental health needs in the military.”

- Sharifian N, LeardMann CA, Kolaja CA, Baccetti A, Carey FR, Castañeda SF, Hoge CW, Rull RP; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Factors associated with mental healthcare utilization among United States military personnel with posttraumatic stress disorder or depression symptoms. Am J Prev Med. 2024 Oct 15:S0749-3797(24)00347-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2024.10.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39419231.