Study Recommends Screening, Possible Alternative Assignment

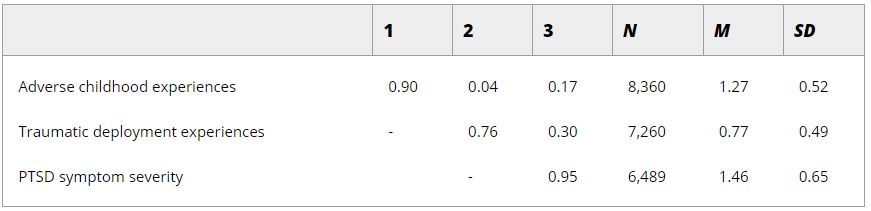

Click to Enlarge: Note: CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; ACES = Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale.

a. Zero-order correlation estimated from frequencies after correction for artificial dichotomization of continuous variables. Source: Journal of Traumatic Stress

AMES, IA — Military servicemembers with a history of physical, emotional or sexual abuse in childhood appear to be at a greater risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) if they are deployed

to conflict zones.

That’s according to a report In the Journal of Traumatic Stress. Iowa State University researchers worked with colleagues in the military and others to help elucidate how adverse experiences early in life can increase vulnerability to trauma later on.

“To understand why some servicemembers develop PTSD symptoms while others don’t, researchers have often looked at how much combat or trauma a servicemember has experienced while deployed,” said the lead authors from Iowa State Marcus Credé, MS, PhD. “Obviously, that matters. But people respond differently, and it seems like some, by virtue of what they went through in childhood, are simply more susceptible.”

The researchers reported on two studies on the topic. “In particular, we examined the evidence for both additive and multiplicative associations between [adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)] and combat exposure in predicting PTSD symptom severity,” they explained.

Study 1 was a meta-analysis of 50 samples, involving 50,000 participants. Evidence for a moderate linear association between ACEs and PTSD symptom severity, ρ = 0.24 was detected. “We also found that ACEs explained substantial variance in PTSD symptom severity after controlling for combat exposure, ΔR2 = .048,” the authors added.

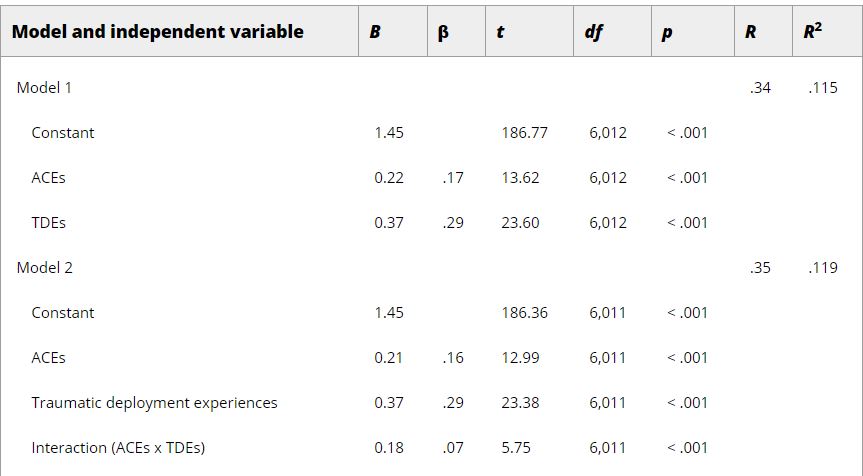

In Study 2, which is preregistered, the study team used a large sample of more than 6,000 combat-deployed U.S. soldiers to examine evidence of a multiplicative association between ACEs and combat exposure in predicting PTSD symptom severity. “In line with theoretical arguments that individuals who have experienced childhood trauma are more vulnerable to subsequent trauma exposure, we found a weak but meaningful interaction effect, ΔR2 = .00, p < .001, between ACEs and deployment-related traumatic events in the prediction of PTSD symptom severity,” the study advised.

Click to Enlarge: Note: Internal consistency estimates are presented along the diagonal. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. Source: Journal of Traumatic Stress

Background information in the article noted that “employees in many occupations, including military servicemembers, first responders, nurses, doctors, and social workers, are frequently exposed to high levels of traumatic stressors, such as death, violence, and threats to their physical safety. The authors added that trauma exposure has been linked to the development of PTSD, which is estimated to affect approximately 7% of United States adults in their lifetime and 13.8% of veterans of recent U.S. military conflicts.

The article noted that PTSD can lead to a range of negative life outcomes, including poor physical health, poor sleep quality and work absences, as well as lower relationship satisfaction and more aggressive behavior toward one’s intimate partner. “Importantly, many of these negative life outcomes are also present in individuals who experience subclinical levels of PTSD,” according to the authors.

A traumatic event is defined by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one “marked by a sense of horror, helplessness, serious injury, or the threat of serious injury or death.” Previous studies have linked frequent and high levels of traumatic stressors, including adverse childhood experiences, to PTSD.”

Disagreements have centered around the strength of the connection and whether the effect is “additive” or “multiplicative.” Credé said “additive” is like putting a weight on a scale, where an adverse childhood experience is one weight and trauma during deployment is another. If the cumulative weight becomes too heavy, he pointed out, PTSD or elevated symptoms can develop.

On the other hand, the multiplicative concept is more like a chemical reaction. Adults might react more strongly to trauma because their system for coping was affected when they were abused as a child.

The first study was a meta-analysis of 50 peer-reviewed journal articles. “Each is a puzzle piece, and we put them together to get a complete picture to find out what is known about adverse childhood experiences with PTSD symptoms on their own and whether it explains PTSD symptoms even after we control for combat exposure. The answer to that is yes,” Credé said.

The second study used preexisting survey responses from servicemembers before they were deployed to Afghanistan, immediately after their return to the United States and then three and six months later.

The dataset provided information about the servicemembers’ childhood experiences, along with trauma exposure during deployment and PTSD symptoms upon return. Traumatic events were not all directly to combat; others included sexual assault and hazing by fellow servicemembers.

Credé said he and his co-authors found evidence that adverse childhood experiences had both additive and multiplicative effects.

Social Support

“If the abuse comes from a parental or authoritative figure in your life, you become wary of people in general, which makes it harder to trust others and form social relationships,” he pointed out, suggesting that social support serves as a key buffer to trauma. “If you’re worried about forming attachments, then you have no one to go to, to say, ‘This is what I’ve been going through.’”

Click to Enlarge: Note: N = 6,016; listwise deletion was used to address missing data. The dependent variable was posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. ACEs = adverse childhood experiences; TDE = traumatic deployment experiences. Source: Journal of Traumatic Stress

The biological mechanism also plays a role, he said, adding, “When you have an elevated cortisol response, even small stressors can lead to a very strong secretion of cortisol. Everything is threatening to you, which is exhausting and can make you more irritable and hypervigilant. It can wear on relationships.”

The authors recommended adding more psycho-education into military training to help servicemembers understand how they might respond to situations and what resources are available. Another suggestion is to screen for adverse childhood experiences. The study said those who are most at risk for PTSD might be better suited for certain positions than others.

“The results offer strong support for the notion that adverse childhood experiences are associated with a nontrivial increase in PTSD symptom severity among servicemembers who have been deployed to combat zones,” the researchers concluded. “This increase appears to be due to both a moderately strong additive effect, such that adverse childhood experiences and traumatic deployment experiences (e.g., combat) combine to predict the severity of PTSD symptoms (Study 1 and Study 2), and a small but meaningful interaction effect that suggests that individuals who have experienced adverse childhood events react more strongly to later trauma exposure (Study 2).”

They emphasized that the finding of a joint additive and multiplicative relationship “significantly expands on prior work concerning the associations among adverse childhood experiences, combat exposure, and PTSD symptom severity that have to this point almost exclusively focused on additive relationships.”

The authors also suggested that the military take into consideration which military personnel is at the greatest risk of PTSD because of childhood abuse. “This study also has practical implications for the military and other organizations that operate in environments where trauma exposure is common (e.g., first responders),” they wrote. “ It may, for example, be possible to develop screening tools that allow individuals to recognize their increased vulnerability to trauma exposure and make appropriate career decisions using this information. This is likely to be particularly valuable if individuals are also explicitly educated about the realities of combat, the psychological and physical risks associated with exposure to combat, and their own vulnerabilities (e.g., their exposure to adverse childhood experiences). Likewise, because many of these organizations have a wide range of positions across many disciplines, leaders could potentially steer candidates with a history of adverse childhood experiences toward less risky work.”

The researchers also endorsed training interventions “to equip service members with coping skills and strategies that will allow them to more effectively manage their prior traumatic experiences as well as any further traumatic events to which they might be exposed during deployment to combat zones.”

- Crede M, Tynan M, Harms PD, Lester PB. Clarifying the association between adverse childhood experiences and post-deployment posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity: A meta-analysis and large-sample investigation. J Trauma Stress. 2023 Jun 7. doi: 10.1002/jts.22940. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37282808.