Largest Nationwide Effort to Compare to Usual Care

Jay Wilson, a retired Wisconsin Army National Guard lieutenant colonel, looks on as his service dog Frosty carries the ceremonial first pitch to home plate to start a Milwaukee Brewers™ game at American Family Field in Milwaukee. Wilson was medically retired in May 2023 after 28 years of military service and multiple combat deployments. A new study could expand the use of service dogs for veterans. Wisconsin Department of Military Affairs. Milwaukee Brewers photo by Kirsten Schmitt

ORO VALLEY, AZ — The VA covers the veterinary care and the equipment costs of service dogs for veterans with physical disabilities such as blindness or vision impairment, but the use of service dogs for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental health issues has remained controversial.

VA leadership has maintained for years that there isn’t enough clinical evidence to prove their benefits for treating mental-health issues. New research has the potential to change that. A nonrandomized controlled trial of 156 military members and veterans with PTSD found that the addition of a service dog to usual care was associated with lower PTSD symptom severity, lower anxiety and lower depression after 3 months of intervention. The trial was led by the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Arizona and involved VA researchers from the Roudebush VAMC in Indianapolis.

“Findings of this trial suggest that trained psychiatric service dogs may be an effective complement to usual care for military service-related PTSD,” the study team wrote in JAMA Network Open.1

VA doesn’t train service dogs but allows veterans, working through their physicians, to get one through accredited partner organizations that provide the animals with training certificates. Based on that, a veteran can request the assistance dog benefit from VA, which includes veterinary care.

Using a service dog benefit is approved for veterans who have mobility issues based on physical impairments such as blindness or deafness. Those who can verify that their mobility is affected by mental health issues also can apply and get the benefit, if the mental health provider and care team can prove that the mental health condition is the primary cause of a veteran’s substantial mobility limitations.

“Military members and veterans (hereafter, veterans) with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increasingly seek psychiatric service dogs as a complementary intervention, yet the effectiveness of service dogs is understudied,” the study researchers pointed out.

That’s why they sought to estimate the associations between psychiatric service dog partnership and self-reported and clinician-rated PTSD symptom severity, depression, anxiety and psychosocial functioning after 3 months of intervention among veterans.

Standardized and validated assessment instruments were completed by trial participants and administered by blinded clinicians, the authors pointed out. They conducted recruitment, eligibility screening and enrollment between August 2017 and December 2019. Veterans were recruited using the database of an accredited nonprofit service dog organization with constituents throughout the United States.

Participants, all veterans with a PTSD diagnosis, were allocated to either the intervention group (n = 81) or control group (n = 75). Outcome assessments were performed at baseline and at the 3-month follow-up. Data analyses were completed in October 2023.

Remaining on Waiting List

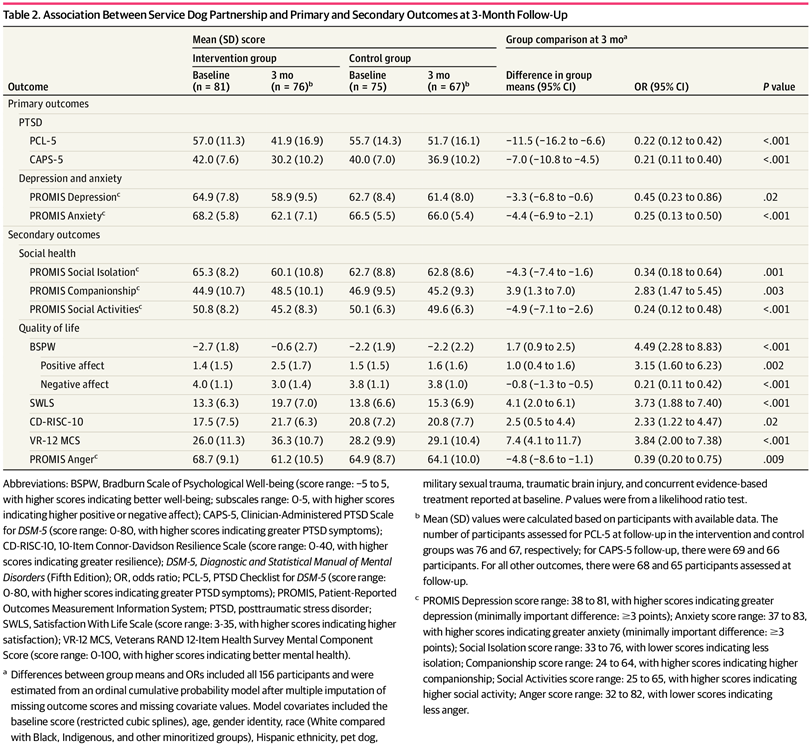

Click to Enlarge: Association Between Service Dog Partnership and Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 3-Month Follow-Up Source: JAMA Network Open

Service dogs for PTSD were provided to participants allocated to the intervention group receiving a psychiatric service dog for PTSD, and members of the control group remained on the waiting list based on the date of application submitted to the service dog organization. Both groups had unrestricted access to usual care.

The 156 participants included in the trial had a mean (SD) age of 37.6 (8.3) years and were 75% male. Most were white, 76%, with 11% Black and 19% Hispanic individuals participating.

Defined as the primary outcomes were PTSD symptom severity, depression and anxiety after 3 months, while the secondary outcomes were psychosocial functioning, such as quality of life and social health. The study team used the self-reported PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) to measure symptom severity, and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) was used to assess PTSD diagnosis (score range for both instruments: 0-80, with higher scores indicating greater PTSD symptoms).

Results indicated that, compared with the control group, the intervention group had significantly lower PTSD symptom severity based on the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 mean (SD) score (41.9 [16.9] vs. 51.7 [16.1]; difference in means, -11.5 [95% CI, -16.2 to -6.6]; P < 0.001) and the CAPS-5 mean (SD) score (30.2 [10.2] vs. 36.9 [10.2]; difference in means, -7.0 [95% CI, -10.8 to -4.5]; P < 0.001) at 3 months. The intervention group also had significantly lower depression scores (odds ratio [OR], 0.45 [95% CI, 0.23-0.86]; difference in means, -3.3 [95% CI, -6.8 to -0.6]), anxiety (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.13-0.50]; difference in means, -4.4 [95% CI, -6.9 to -2.1]) and most areas of psychosocial functioning (e.g., social isolation: OR, 0.34 [95% CI, 0.18-0.64]).

“This nonrandomized controlled trial found that compared with usual care alone, partnership with a trained psychiatric service dog was associated with lower PTSD symptom severity and higher psychosocial functioning in veterans,” the researchers concluded. “Psychiatric service dogs may be an effective complementary intervention for military service-related PTSD.”

Background information in the article pointed out that PTSD “is a pressing concern for military members and veterans (hereafter, veterans), with an estimated prevalence of 23% among those with post-9/11 service. Post-traumatic stress disorder is characterized by symptoms of intrusion, avoidance of trauma reminders, adverse alterations in cognition and mood, and increased arousal and reactivity. By definition, disturbances must lead to clinically significant distress and/or impairment in areas of social, occupational, or other functioning.”

In addition, the study noted that PTSD is associated with a range of comorbid conditions, including major depression and generalized anxiety disorder, and veterans are 1.5 times more likely to die by suicide than nonveteran adults.

“Currently, PTSD remains difficult to treat. Existing evidence-based treatments for PTSD are effective for some individuals, but uptake and retention are limited,” the authors explained. “Veterans are increasingly seeking out psychiatric service dogs (hereafter, service dogs) as complementary interventions. However, the effectiveness of service dogs remains understudied.”

Service dogs, referred to as “assistance dogs” internationally, are defined under U.S. federal law as “dogs that are individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities.”

“While preliminary evidence indicated that service dog partnerships are associated with meaningful improvements in self-reported PTSD symptoms for veterans with PTSD, only one clinical trial on their efficacy has been conducted to date, which compared emotional support dogs to service dogs, precluding conclusions about service dogs compared with usual care alone. Moreover, no studies of service dogs have used blinded or masked clinician ratings to evaluate PTSD severity outcomes. Therefore, a clinical trial using a no-dog comparison condition with blinded clinician ratings is needed to fill these gaps” the researchers advised.

They said their research is the largest nationwide study to date to compare service dog partnerships with usual care alone, and is the first National Institutes of Health–funded study to investigate service dog partnerships for military service-related PTSD.

- Leighton SC, Rodriguez KE, Jensen CL, et al. Service Dogs for Veterans and Military Members With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2414686. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.14686