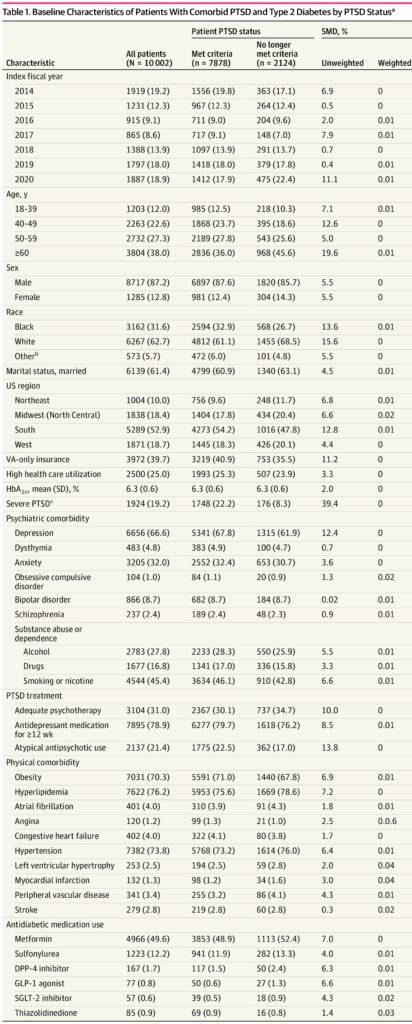

Click to Enlarge: Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Comorbid PTSD and Type 2 Diabetes by PTSD StatusaAbbreviations: DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; PCL, PTSD Checklist; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SGLT-2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2; SMD, standardized mean difference; VA, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

a. Unless indicated otherwise, values are presented as the No. (%) of patients.

b. Defined as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

c. First PCL score of 66 or greater. Source: JAMA Network Open

ST. LOUIS — Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has a range of adverse effects in veterans, and about 7% are affected at some point in their lifetimes. A recent study puts a spotlight on an unexpected co-morbidity—worsening Type 2 diabetes (T2D) outcomes.

In the cohort study of 10,002 veterans, no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD was associated with a lower risk of microvascular complications with T2D.

“Among veterans aged 18 to 49 years, but not among those aged 50 to 80 years, no longer meeting PTSD criteria was associated with a lower likelihood of starting insulin and a lower risk of all-cause mortality”, wrote the Saint Louis University School of Medicine-led researchers and colleagues from the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans’ Hospital in Columbia, MO, the VA’s National Center for PTSD, White River Junction, VT, the San Francisco VAMC and elsewhere.

The results of the study, published in JAMA Network Open, raised the possibility that PTSD is a modifiable risk factor for some adverse T2D outcomes among patients with comorbid PTSD and T2D.1

Reduction of PTSD symptoms is linked with lower risk of incident T2D, but little else is known about the association between PTSD and comorbid T2D outcomes, the study team noted. As a result, the researchers sought to determine whether patients with PTSD who improved and no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD had a lower risk of adverse T2D outcomes compared with patients with persistent PTSD.

Their retrospective cohort study used disidentified data from VHA medical records from Oct. 1, 2011, to Sept. 30, 2022, to create a cohort of patients aged 18 to 80 years with comorbid PTSD and T2D. Data analysis was performed from March 1 to June 1, 2024.

Defined as the study’s main outcomes were insulin initiation, poor glycemic control, any microvascular complications and all-cause mortality.

At the same time, the authors tracked improvement of PTSD, which was defined as no longer meeting PTSD diagnostic criteria, per a PTSD Checklist score of less than 33. Subgroup analyses examined variation by age, sex, race, PTSD severity and comorbid depression status.

Included in the study cohort were 10,002 veterans, with more than half of patients (65.3%) aged 50 and older; most (87.2%) were men. The patients identified as Black (31.6%), white (62.7%) or other race (5.7%).

“Before controlling for confounding with entropy balancing, patients who no longer met PTSD diagnostic criteria had similar incidence rates for starting insulin (22.4 vs. 24.4 per 1,000 person-years), poor glycemic control (137.1 vs. 133.7 per 1,000 person-years), any microvascular complication (108.4 vs. 104.8 per 1,000 person-years), and all-cause mortality (11.2 vs. 11.0 per 1,000 person-years) compared with patients with persistent PTSD,” according to the report.

After controlling for confounding, however, no longer meeting PTSD criteria was associated with a lower risk of microvascular complications (hazard ratio [HR], 0.92 [95% CI, 0.85-0.99]).

“Among veterans aged 18 to 49 years, no longer meeting PTSD criteria was associated with a lower risk of insulin initiation (HR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.53-0.88]) and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.39 [95% CI, 0.19-0.83]),” the authors pointed out. “Among patients without depression, no longer meeting PTSD criteria was associated with a lower risk of insulin initiation (HR, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.55-0.97]).”

The study team called for further research to determine whether findings are similar in non-VHA healthcare settings. Results were published in JAMA Network Open.1

Background information in the study advised that patients with psychiatric disorders have a 20-year shorter life expectancy than those without mental illness, “and despite advances in treatment, there has been little to no narrowing of the mental health disparity in mortality over the past 30 years. This disparity in mortality may be related to the association between mental illness and poor metabolic health.”

Incident Diabetes

The authors cited that PTSD is associated with a significantly increased risk of incident T2D, adding. “Patients with comorbid PTSD and T2D have worse glycemic control, increased risk of hospitalization, and poorer self-reported health compared with patients with T2D alone.”

Yet, whether PTSD might be a modifiable risk factor for T2D and adverse T2D outcomes remained unclear.

It was known that treatment of PTSD and reduction in PTSD severity were linked to greater uptake of health-promoting behaviors such as smoking cessation and initiation of weight-loss programs, while improvement of PTSD in comorbid psychiatric illness is associated with better overall well-being and with lower risk of some chronic health conditions, including T2D.

“To our knowledge,” the researchers wrote, “there is no existing literature on T2D outcomes after PTSD improvement among patients with comorbid PTSD and T2D. This study aimed to help fill this gap in the literature. If there is a reduced risk of adverse T2D outcomes among patients with PTSD who experience improvement and no longer meet PTSD criteria, then findings could be used to incentivize PTSD treatment and patients should be educated that improvement in PTSD may benefit comorbid T2D management.”

The study team added, “It is logical that younger, adult VHA patients would have a reduced risk of insulin initiation and mortality because the accumulation of comorbid conditions that contribute to poor health outcomes increases with aging and likely limits the ability to detect associations between PTSD improvement and T2D outcomes in those aged older than 50 years.”

That patients without depression and no longer meeting PTSD criteria were statistically significantly less likely to start insulin was consistent with prior observations that PTSD is associated with poor glycemic control, the article pointed out. “In addition, this finding is aligned with the link between depression and hyperglycemia41 and is consistent with evidence that depression and correlated inflammation and oxidative stress increase risk of poor T2D outcomes,” the authors explained. “This finding could also be related to poor diabetes self-management and poor medication adherence among persons with PTSD and depression.”

The report emphasized that the VHA outperforms the civilian sector in T2D treatment, with a much higher percentage of VHA patients achieving control than the private sector. “It is possible the increases in insulin use that we observed in some subgroups reflect intensification of medications that prevented patients from crossing thresholds for poor control,” the authors noted. “With such well-managed T2D, we may have lacked sufficient variability in HbA1c values in follow-up to detect an association with PTSD improvement.”

- Scherrer JF, Salas J, Wang W, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Type 2 Diabetes Outcomes in Veterans. JAMA Netw. Open. 2024;7(8):e2427569. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.27569