In the Paktika Province in Afghanistan in 2011, medical personnel from the 2nd Forward Surgical Team prepare a civilian for surgery after an insurgent improvised explosive device near her home critically injured her. Photo by Staff Sgt. Charles Crail

PALO ALTO, CA — Moral distress—characterized as overwhelming feelings of being powerless to do what is believed to be right—and moral injury—trauma from an event generates significant dissonance with the individual’s belief system and worldview—are topics of increasing interest and research in civilian health care professionals and combat soldiers.

Yet a new VA study may be the first to examine moral injury and distress at the intersection of these populations—that is, military healthcare professionals, specifically surgeons, said Sherry Wren, MD, a general surgeon with the VA Palo Alto, CA, Health Care System and Stanford Health Care.

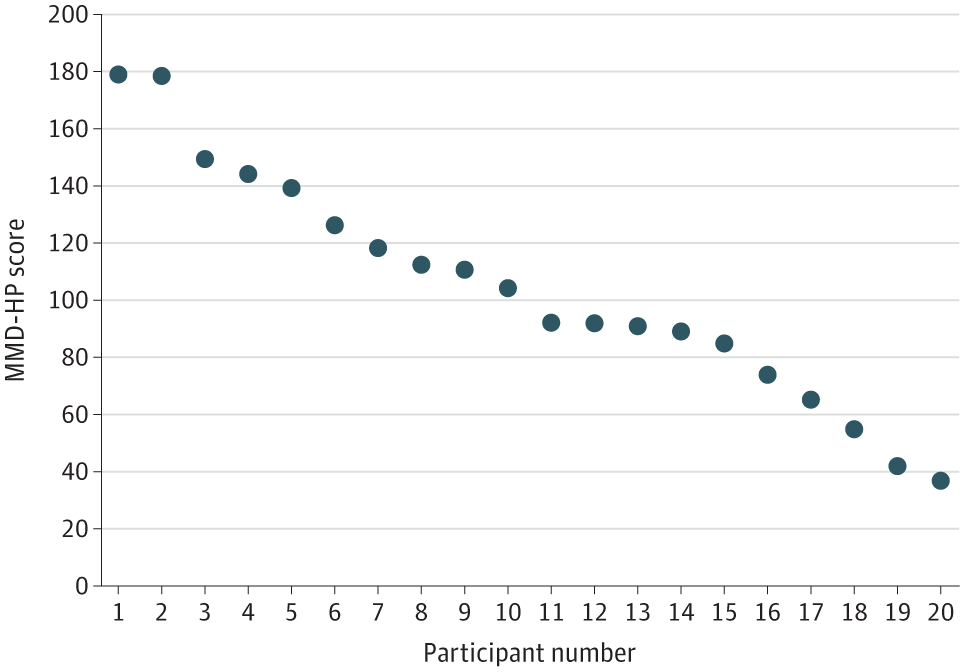

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, involved administering the Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) survey—the most commonly used tool for civilian health care professionals worldwide—along with individual, semi-structured interviews with 20 combat surgeons recruited through snowball sampling through authors’ personal contacts.1

All participants were military surgeons who had deployed to a far-forward Role 2 military treatment facility—defined as an environment close to combat action with basic resuscitative and surgical capabilities but little to no diagnostic tools or imaging technology—in Iraq or Afghanistan during peak casualty times.

The key finding was that civilian measures don’t fully capture the stressors or address the unique needs of the deployed military doctors, said Wren, who undertook the study, in part, because of her own experience working in combat zones as a humanitarian actor for Doctors Without Borders.

Click to Enlarge: Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MMD-HP) Survey Tool overall composite MMD-HP score for each participant. Source: JAMA Network Open

The study revealed one of the biggest differences in the stressors between civilian and military surgeons were related to the Medical Rules of Engagement (MROE), which are battlefield-specific rules governing the delivery of medical care to military personnel and local national civilians. Within the domain of MROE, the most common source of distress reported by all 20 surgeons was the policy that required transfer of civilian casualties to local facilities that often could not provide the level of care needed. “Surgeons reported that they would assume or even know with certainty that their patients died after transfer,” the authors wrote. “They reported that it was especially distressing watching the work and resources committed to the patient at their facility be for nothing when the patients were transferred to a facility that was unable to maintain the same level of care.”

The other domain revealed by survey responses was distressing outcomes, which fell into three themes: horrifying injuries of war, patient populations and second-guessing and regret.

Horrifying Injuries of War

All surgeons interviewed expressed substantial distress from witnessing horrific injuries, largely due to military weaponry and severe burn and blast injuries, according to the study.

One participant said: “The devastation of the injury cannot be duplicated by civilian trauma. Your trauma training and residency can’t match it, no matter how bad it is. It’s just devastating. That shock takes a little bit to get over.”

Patient Populations

Participants said they often had the hardest time dealing with casualties involving children, pregnant women and U.S. soldiers. Eleven of the 20 soldiers felt that treating U.S. soldiers was particularly distressing because they felt connected to these patients in a deeper way. Some personally knew not only the soldiers themselves, but also their families.

Second-guessing and Regret

A common feeling expressed by 14 of 20 of the surgeons was one of second-guessing and regretting some of the decisions that they were forced to make during deployment. Furthermore, surgeons said that they were not trained to do some operations that were required of them, which led to second-guessing of decisions made before and during surgical procedures. The surgeons also said that the limited resources, personnel and poor outcomes experienced during the deployment also made them question the decisions they had to make and their own surgical abilities in very stressful situations.

Sources of distress manifested both during after the deployment, the study found. Moral injury and distress most commonly manifested in sleep disorders and problems with interpersonal relationships and medical practice. Four of 20 surgeons discussed vivid nightmares after deployment.

A Need for New Tools

In addition to the MMD-HP survey for healthcare professionals, there are several instruments to assess moral injury and distress in active duty-persons or veterans; however, these are centered around combat experience (e.g., killing or violent acts) and, therefore, lack specific granularity to the military practice of medicine, the authors stated.

At the time of the study, there was no specific tool for military health professionals, but in 2019 the TriService Nursing Research Program received funding to adapt the MMD-HP to assess moral injury and distress in TriService military critical care nurses, said Wren. The adapted survey, MMD-HP-M, added 10 military environment-specific questions. At present, the survey has undergone one validation study in active-duty military nurses. Once it is further defined and validated with a deployed military physician or surgeon cohort, the survey could represent an advance in the characterization of moral injury and distress in this unique population, the authors wrote.

Although the study was small, Wren said the findings show a need to better understand the experience of moral injury and distress in combat surgeons and a need for specialized tools to screen for them.

“We need to have better screening tools, because I think we also showed these scars last for a long time,” she said. “I know personally I have been haunted by decisions that I made when I was working in these types of resource-limited settings that have haunted me for years, and that’s a very tough thing. We need to make sure we are taking care of the mental health of people, providing very complicated care in these unique settings.”

- Ryu MY, Martin MJ, Jin AH, Tabor HK, Wren SM. Characterizing Moral Injury and Distress in US Military Surgeons Deployed to Far-Forward Combat Environments in Afghanistan and Iraq. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Feb 1;6(2):e230484. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0484. PMID: 36821112; PMCID: PMC9951040.