Sgt. Matthew Roberts, along with fellow members of Company B, 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, patrols the Korengal valley in Afghanistan’s Kunar province, during the early morning hours of Aug. 1, 2009. Battle can create acute stress reaction in some soldiers. U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Matthew Moeller

SILVER SPRING, MD — A recent report from military researchers put the spotlight on combat-related acute stress reactions (ASRs) in servicemembers.

ASRs are not regarded as a clinical disorder but “can have a significant impact on high-risk occupations like the military in which impaired functioning can imperil team members and others,” noted the authors from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, MD.

“Based on self-report, 17.2% of soldiers who have deployed to combat report having experienced a possible ASR,” they advised. “To our knowledge, this is the first such prevalence estimate.”

Their article in Current Psychiatry Reports emphasized that “the prevalence of ASRs underscores the need for improved prevention, management and recovery strategies. Peer-based intervention protocols such as iCOVER may provide a useful starting point to address ASRs in team members.”1

The authors’ goal was to contrast ASRs with related psychiatric conditions, report the estimated prevalence of ASRs for soldiers deployed to combat, and consider how team members can effectively respond to these reactions.

The article included the following scenario: “A small team of soldiers is on a mission to rescue stranded civilians and bring them out of a hostile country. The environment is harsh, the smells and sounds disorienting. Tension is high. As the team moves forward, they are ambushed by enemy combatants; they quickly take cover in an abandoned building. As they begin to respond to the threat, one soldier freezes in place, unable to return fire or follow directions. The situation is dangerous: the soldier is unable to act, and the team needs the soldier to snap back into action. What can the team members do?”

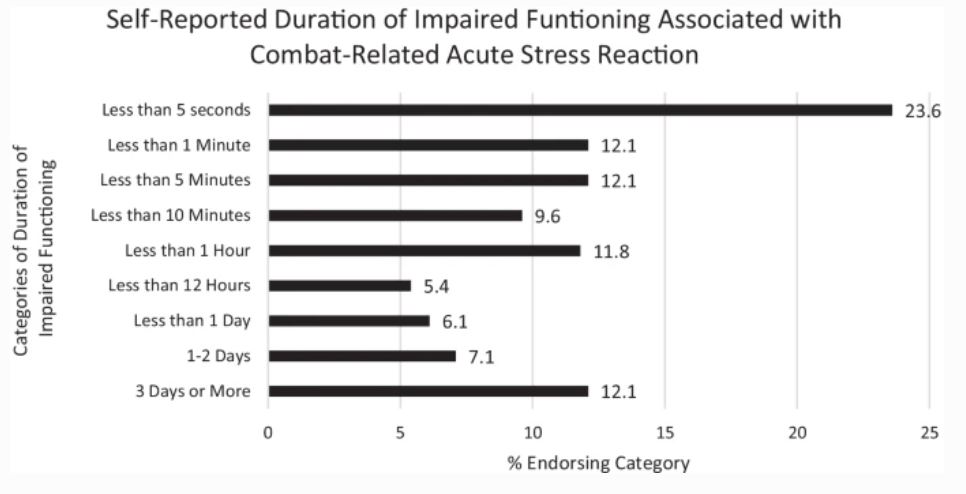

Click to Enlarge: Self-reported duration of impaired functioning and combat-related acute stress reaction. Source: Curr Psychiatry Rep 24, 277–284 (2022).

The authors, Amy B. Adler, PhD, and Ian A. Gutierrez, PhD, suggested that a war-fighter frozen with fear isn’t really considered unusual in situations such as combat. In fact, movies, such as “Saving Private Ryan,” often depict it. “Although these moments are ubiquitous in fiction, it is only recently that there have been systematic attempts to understand and manage these moments of acute stress in real-world military operations,” they wrote.

According to the report, an ASR is defined in the International Classification of Disease, 11th edition (ICD 11; version 5/2021) as “the development of transient emotional, somatic, cognitive, or behavioral symptoms as a result of exposure to an event … of an extremely threatening or horrifying nature.”

Symptoms range from autonomic signs of anxiety, such as increased heart rate, sweating and rapid breathing, to cognitive signs of anxiety, such as disorientation, non-responsiveness or hyper-alertness. ASR can cause both stupor or overactivity. What makes it different from conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder is that the reactions “subside within a few days after the event or following removal from the threatening situation.”

The authors pointed out that, while ASR appears in the ICD 11, it is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), explaining, “It may be that ASR is excluded in the DSM-5 because it is not considered a disorder, but rather a natural disruption in functioning in the midst of extreme stress that should not be medicalized. In fact, ASR is defined in the ICD as “normal given the severity of the stressor.”

They added, “Whereas ASRs are fear-based responses to present real-world dangers, anxiety disorders manifest from an anticipation of possible future dangers owing to their occurrence in the past. The absence of a DSM-5 diagnosis for ASRs may also suggest that these symptoms are too transitory to be seen in a clinical setting or merit diagnosis. In other words, because servicemembers may be in dire straits temporarily and then quickly recover, clinicians may not encounter patients with this particular symptom profile.”

DSM-5 does include a diagnosis for acute stress disorder (ASD), however. As opposed to ASR, ASD involves intrusion symptoms, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance and arousal, with symptoms defined as beginning after exposure to a traumatic stressor and lasting for at least three days and not longer than a month.

“Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be diagnosed for individuals reporting similar symptoms from four clusters (intrusion symptoms, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity) lasting more than a month and leading to distress or functional impairment,” the authors advised.

The momentary and shifting set of psychological and physiological symptoms during a high-stress event might occur suddenly, with speedy recovery, but Adler and Gutierrez cautioned, “While the individual may recover quickly, for occupations that require individuals to operate under duress, even momentary breaks in functioning increase risk to the individual, teammates and the mission.”

They explained that ASRs can also occur in occupational fields such as policing, firefighting, and emergency medicine.

A protocol developed at Walter Reed Institute of Research is designed to treat panic attacks or severe claustrophobic symptoms in warfighters wearing protective gear, as well as other acute stress reactions.

The six-step system, iCover, is:

- Identify the individual experiencing an acute stress reaction.

- Connect with the individual by speaking their name, making eye contact, and holding their arm.

- Offer commitment by letting them know they are not alone.

- Verify facts with two to three simple questions to get their thinking kickstarted (e.g., “What hospital is this?” and “What section of the hospital are you in?”)

- Establish an order of events to ground them in the present moment by stating what happened, what is happening, and what needs to happen in three simple sentences. (e.g., “You donned your PPE. You are checking the seal. We are about to check on a patient.”)

- Request action of the individual to restore them to purposeful behavior (e.g., “Double-check the oxygen saturation on that patient and report back.”)

“Indeed, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, behavioral health providers supporting medical personnel in the civilian healthcare system reached out to the Army’s team responsible for iCOVER and asked for iCOVER to be adapted for medical staff,” Adler and Gutierrez noted. “Medical teams were experiencing profound levels of acute stress as they responded to massive numbers of casualties at a relentless pace. iCOVER-Med was quickly developed and disseminated. While the steps remained the same, the rationale and examples were created for the medical context.”

The study called for future research on ASRs.

- Adler AB, Gutierrez IA. Acute Stress Reaction in Combat: Emerging Evidence and Peer-Based Interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24(4):277-284. doi:10.1007/s11920-022-01335-2