PALO ALTO, CA — Growing evidence from observational studies signals that prescribing multiple antihypertensive prescriptions might do more harm than good in older patients with polypharmacy and comorbid conditions.

That can leave clinicians in a precarious position. While guidelines recommend using clinical judgment when prescribing the drugs to frail older patients, including the possibility of deprescribing, they tend to be nonspecific on when and how to do that.

A study of older adults living in VA long-term care facilities looked at the incidence of deprescribing of antihypertensive medication, as well as how potentially triggering events affected those decisions. Results were published in JAMNDA.1

Included in the retrospective cohort study were long-term care residents age 65 years and older admitted to a VA nursing home from 2006 to 2019 and using blood pressure medication at admission.

VA Palo Alto Healthcare System and Stanford University researchers extracted data from the VA electronic health record, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set and Bar Code Medication Administration. Deprescribing was defined as a reduction in the number or dose of antihypertensive medications for two weeks or more.

The study team also assessed potentially triggering events for deprescribing, including low blood pressure (<90/60 mmHg), acute renal impairment (creatinine increase of 50%), electrolyte imbalance (potassium below 3.5 mEq/L, sodium decrease by 5 mEq/L), and falls and how that affected the residents’ drug regimens.

Results indicated that, among 31,499 VA nursing home residents on antihypertensive medication, 70.4% had one or more deprescribing event over a median length of stay of six months, and 48.7% had a net reduction in antihypertensive medications over that stay.

The study found that deprescribing events were most common in the first four weeks after admission and the last four weeks of life. “Among potentially triggering events, a 50% increase in serum creatinine was associated with the greatest increase in the likelihood of deprescribing over the subsequent four weeks: Residents with this event had a 41.7% chance of being deprescribed compared with 11.5% in those who did not (risk difference = 30.3%, P < 0.001). A fall in the past 30 days was associated with the smallest magnitude increased risk of deprescribing (risk difference = 3.8%, P < 0.001) of the events considered,” the authors wrote.

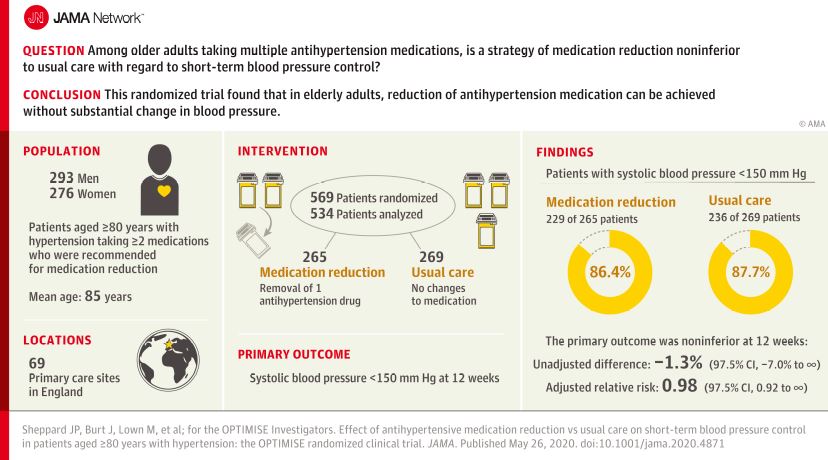

Last year, a UK study, published in JAMA, asked whether a strategy of antihypertensive medication reduction was noninferior to usual care short-term blood pressure control in older adults on multiple agents. 2

University of Oxford researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial that included 569 patients age 80 years and older, finding that the proportion with systolic blood pressure lower than 150 mm Hg at 12 weeks was 86.4% in the intervention group—where drugs had been prescribed—vs. 87.7% in the control group (adjusted relative risk, 0.98), a difference that met the non-inferiority margin of a relative risk of 0.90.

“The findings suggest antihypertensive medication reduction can be achieved without substantial change in blood pressure control in some older patients with hypertension,” the authors wrote.

The Optimizing Treatment for Mild Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly (OPTIMIzE) study was a randomized, non-blinded, non-inferiority trial conducted in 69 primary care sites in England.

Included were participants whose primary care physician considered them appropriate for medication reduction; all 80 years old and older, had systolic blood pressure lower than 150 mm Hg and were receiving at least two antihypertensive medications. The final group had a mean age of 84.8, were 48.5% women, and took a median of two antihypertensive medications.

Enrollment occurred between April 2017 and September 2018, and participants underwent follow-up until January 2019.

Removal of One Drug

The intervention was the removal of one drug in 282 patients compared to usual care, with no medication changes, in 287. Defined as the primary outcome was systolic blood pressure lower than 150 mm Hg at 12-week follow-up.

Researchers advised that the prespecified non-inferiority margin was a relative risk (RR) of 0.90, while secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants maintaining medication reduction and differences in blood pressure, frailty, quality of life, adverse effects and serious adverse events.

Results indicated that, overall, 229 (86.4%) patients in the intervention group and 236 (87.7%) patients in the control group had a systolic blood pressure lower than 150 mm Hg at 12 weeks (adjusted RR, 0.98 [97.5% 1-sided CI, 0.92 to ∞]). Of seven prespecified secondary end points, five showed no significant difference.

The authors pointed out that medication reduction was sustained in 187 (66.3%) participants at 12 weeks. They added that mean change in systolic blood pressure was 3.4 mm Hg (95% CI, 1.1 to 5.8 mm Hg) higher in the intervention group compared with the control group. At least one serious adverse event was reported in 12 (4.3%) participants in the intervention group and 7 (2.4%) in the control group (adjusted RR, 1.72 [95% CI, 0.7 to 4.3]).

“Among older patients treated with multiple antihypertensive medications, a strategy of medication reduction, compared with usual care, was non-inferior with regard to systolic blood pressure control at 12 weeks,” the researchers concluded. “The findings suggest antihypertensive medication reduction in some older patients with hypertension is not associated with substantial change in blood pressure control, although further research is needed to understand long-term clinical outcomes.”

Background information in the study explained how fraught the issue can be for prescribers. “High blood pressure is the leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease3 and the most common comorbid condition in older people with multi-morbidity,” the authors wrote. “Anti-hypertensive treatment prevents stroke and cardiovascular disease in older high-risk patients, and approximately half of individuals aged 80 years or older are prescribed therapy. However, previous trials such as the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention (SPRINT) trial have been shown to represent as few as one-third of older individuals in the general population, and there is debate about the extent to which these data should be applied to frail patients with multi-morbidity.”

Researchers decried that so few randomized clinical trials have considered the safety and efficacy of antihypertensive medication reduction in routine clinical practice. “In older patients with multi-morbidity and controlled blood pressure (<150/90 mm Hg), there are advantages and disadvantages to continuing treatment. For patients whose physicians determine that potential risks of continuing treatment outweigh benefits, there is no evidence to guide medication reduction,” they added.

- Odden MC, Lee SJ, Steinman MA, Rubinsky AD, Graham L, Jing B, Fung K, Marcum Z, Peralta CA. Deprescribing Blood Pressure Treatment in Long-Term Care Residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 Aug 5:S1525-8610(21)00647-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.07.009. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34364847.

- Sheppard JP, Burt J, Lown M, et al. Effect of Antihypertensive Medication Reduction vs Usual Care on Short-term Blood Pressure Control in Patients With Hypertension Aged 80 Years and Older: The OPTIMISE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2039–2051. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4871