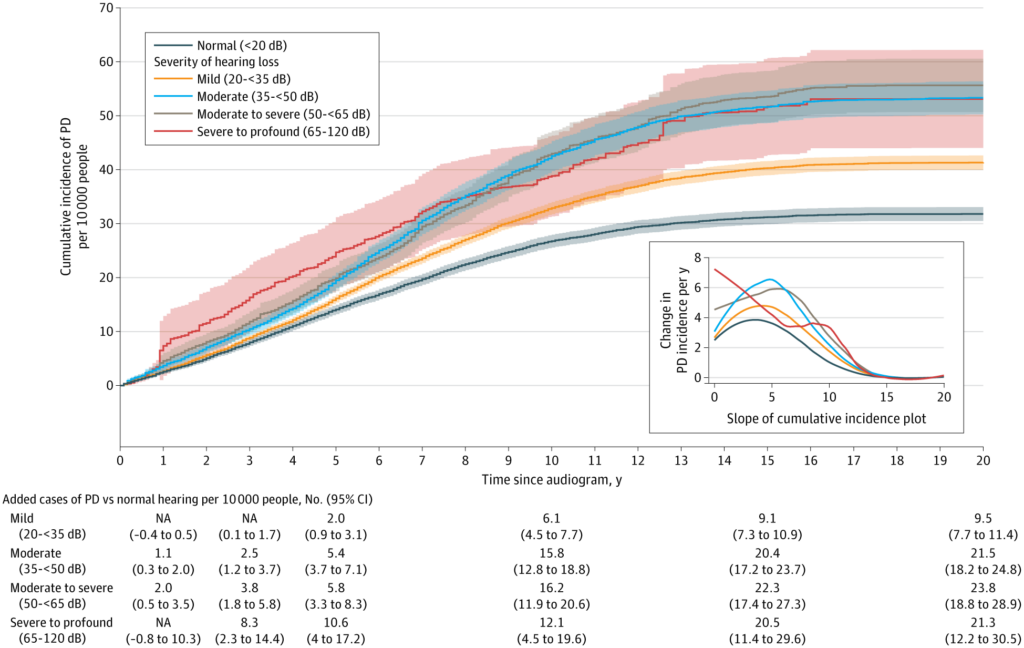

Click to Enlarge: Hearing Loss and Subsequent Parkinson Disease (PD)Cumulative incidence of PD during the 20 years after a baseline audiometry examination. Participants were assigned into groups using World Health Organization criteria based on pure tone thresholds at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz into normal hearing (<20 dB) or categories of hearing loss, including mild, moderate, moderate to severe, and severe to profound. Cumulative incidence is shown with 95% CIs after adjustment for confounders and competing risk of death. The inset shows the slope of the cumulative incidence curves for each respective category. Tabulated differences are shown for normal hearing vs hearing loss at 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after the baseline audiometry examination. NA indicates not available. Source: JAMA Network Open

PORTLAND, OR — A complex and progressive neurological disorder, Parkinson’s disease (PD) has been diagnosed in more than a million Americans and disproportionately impacts veterans. While there is no cure for the disease, identifying potentially modifiable prodromal symptoms, and ultimately intervening, could not only delay decline in quality of life but also substantially reduce the future economic burden of the disease, according to a new study.

A considerable amount of research has focused on visual changes and loss of smell in early Parkinson’s, but there have been just a few small studies on hearing loss, explained Lee Neilson, MD, lead author of large VA study, which had intriguing—and in some ways, hopeful—findings about the association between hearing loss and PD risk.

The study, published in JAMA Neurology, examined data from more than 3.6 million veterans using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), a nationwide relational database of electronic health records. Unlike previous research that often relied on diagnostic codes or patients’ self-reported hearing loss—both prone to significant inaccuracies—this new study used audiometry data, explained Neilson, a staff neurologist at Portland VA Medical Center. “This gave the researchers a quantifiable measure of hearing loss and further allowed them to stratify by severity and determine if the degree of hearing loss had any impact on risk of PD,” he noted.1

After settling on the “right cohort of veterans,” the researchers looked at the veteran’s first audiogram and classified their hearing as normal or abnormal; they then rated the severity of hearing loss in those classified as abnormal.

“We then followed them forward in time to see what happened—did they get Parkinson’s? Are they still healthy? Did they die?” he said. “While the average follow-up time was 7 years, we had records for some people extending out to 20 years.” The researchers then asked if there might be other systematic differences, such as racial background or smoking status, that could explain or confound the initial results. Finally, they tried to validate their results using a few alternative approaches to lend more certainty to our initial findings, he said.

The study had four major findings, Neilson told U.S. Medicine.

- Hearing loss is associated with a higher risk of developing PD later in life, independent of other known risk factors for PD;

- Those veterans with the most severe hearing loss had the highest risk of developing PD;

- In those with hearing loss and at least one other condition known to be a risk factor of PD (such as constipation or orthostatic hypotension), their risk was synergistic (i.e., greater than simply adding the risks together);

- Veterans who were given a hearing aid within two years of a hearing test had a reduced risk of developing PD.

“We were quite surprised—but excited—to find that if veterans had documented evidence of receiving a hearing aid within 2 years of a hearing test, they had a lowered risk of PD later in life,” Neilson said. “We can’t quite wrap our heads around why this might work, and biological plausibility is an important consideration when ascribing causality. While we were delightfully surprised, there is more work to do to figure out how this intervention might work and if we can learn more about the precise groups who are going to most benefit.”

While Neilson underscored that correlation does not equal causation, he said the study’s findings that objective hearing loss is associated with the later development of PD add to the mounting evidence that hearing is important to human health. “We trust that policymakers and others will consider these findings in light of all available research and that future studies will also examine this association within the patient population,” he said.

For now, the study sends an important message to physicians, Neilson said. “For clinicians, even the busiest of primary care providers, adding a brief hearing screen to the annual wellness visit could improve quality of life for our veterans now and in the future,” he said. “This is especially important in the veteran population because of the great access to audiology in this system, which is not easily found in the community.”

- Neilson LE, Reavis KM, Wiedrick J, Scott GD. Hearing Loss, Incident Parkinson Disease, and Treatment With Hearing Aids. JAMA Neurol. 2024 Oct 21. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.3568. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39432289.