Study: Practice Has Little Benefit But High Rates of Adverse Effects

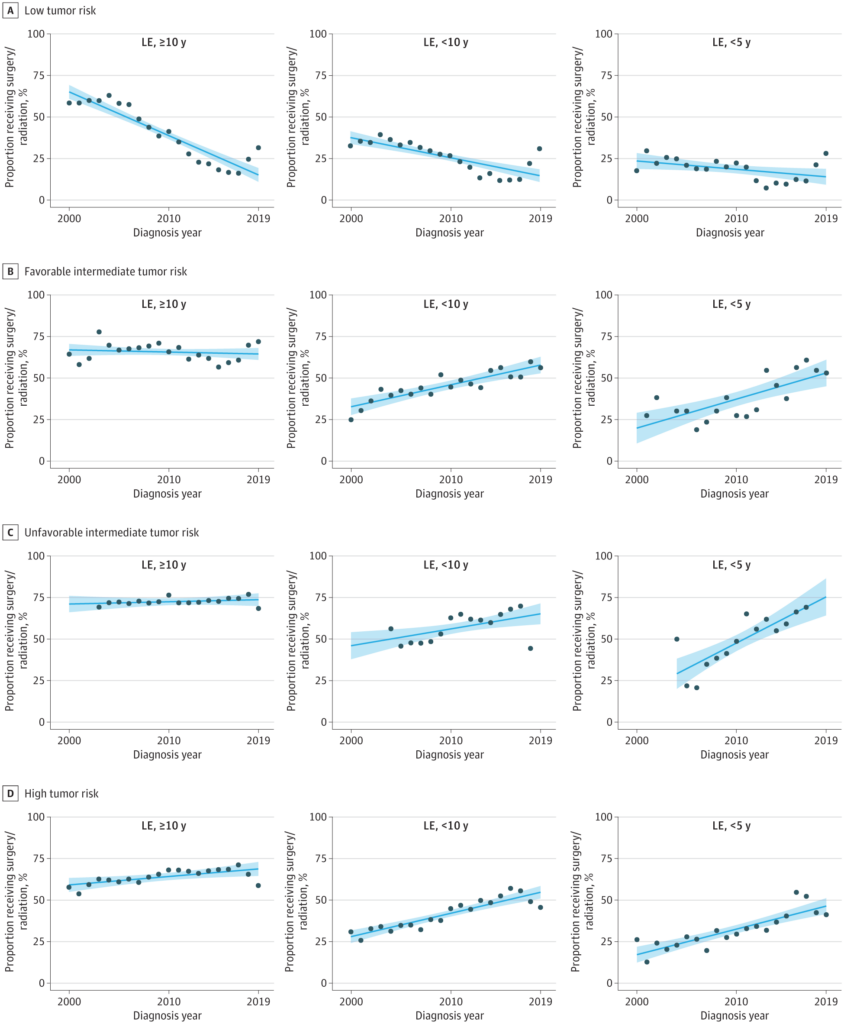

Click to Enlarge: Trends in Definitive Treatment for Men With Localized Prostate Cancer by Life Expectancy (LE) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network Tumor Risk CategoryShaded areas indicate 95% CIs. Data points with fewer than 10 participants were omitted. Source: JAMA Network

LOS ANGELES — Overtreatment, especially with radiotherapy, has increased for veterans with limited life expectancy and intermediate-risk or high-risk prostate cancer, according to a new study.

At the same time, according to the report in JAMA Internal Medicine, overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer with surgery or radiotherapy decreased.1

“Men with limited life expectancy (LE) have historically been overtreated for prostate cancer despite clear guideline recommendations. With increasing use of active surveillance, it is unclear if overtreatment of men with limited LE has persisted and how overtreatment varies by tumor risk and treatment type,” wrote the researchers from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, Stanford University in Stanford, CA, and the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System.

Their cohort study of 243,928 men with clinically localized prostate cancer in the VA health system asked whether overtreatment of prostate cancer with definitive local therapy among men with limited life expectancy is increasing in the active surveillance era?

The study team pointed out that, while there has been a significant reduction in overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer in the VA related to the adoption of active surveillance, “clinicians should also avoid definitive treatment of men with limited life expectancy to prevent unnecessary toxic effects in men with insufficient longevity to benefit from treatment.”

Background information in the article advised that men with limited life expectancy (LE) have historically been overtreated for prostate cancer despite clear guideline recommendations. This study zeroed in on how much overtreatment has persisted and whether it differed by tumor risk and treatment type.

The study included VA health system patients who received a diagnosis between Jan.1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2019. The mean age was 66.8, and 205 and 4.7% had life expectancies of less than 10 years 5 years, respectively. Those were based on the Prostate Cancer Comorbidity Index (PCCI).

Results indicated that, among men with an LE of less than 10 years, the proportion of men treated with definitive treatment (surgery or radiotherapy) for low-risk disease decreased from 37.4% to 14.7% (absolute change, −22.7%; 95% CI, −30.0% to −15.4%). At the same time, however, it increased for intermediate-risk disease from 37.6% to 59.8% (22.1%; 95% CI, 14.8%-29.4%) from 2000 to 2019, with increases observed for favorable (32.8%-57.8%) unfavorable intermediate-risk disease (46.1%-65.2%).

Among men with an LE of less than 10 years who were receiving definitive therapy, the predominant treatment was radiotherapy (78%), the authors explained, adding that, among men with an LE of less than 10 years, use of radiotherapy increased from 31.3% to 44.9% (13.6%; 95% CI, 8.5%-18.7%) for intermediate-risk disease from 2000 to 2019, with increases observed for favorable and unfavorable intermediate-risk disease.

The predominant treatment also was radiotherapy (85%) among men with an LE of less than 5 years; the proportion of those men treated with definitive treatment for high-risk disease increased from 17.3% to 46.5% (29.3%; 95% CI, 21.9%-36.6%) from 2000 to 2019. Among men with an LE of less than 5 years, use of radiotherapy increased from 16.3% to 39.0% (22.6%; 95% CI, 16.5%-28.8%) from 2000 to 2019, the researchers reported.

“The results of this cohort study suggest that, in the active surveillance era, overtreatment of men with limited LE and intermediate-risk and high-risk prostate cancer has increased in the VA, mainly with radiotherapy,” the authors concluded.

They noted that life expectancy is a key factor in treatment decision-making for men with clinically localized prostate cancer because limited LE is associated with:

- a lower likelihood of sufficient longevity to benefit from treatment,

- higher morbidity after treatment, and

- decreased treatment effectiveness.

Guidelines on Life Expectancy

“During the last decade, LE has been formally incorporated into PC treatment guidelines, which recommend against aggressive therapy for those with an LE of less than 10 years and low-risk and some intermediate-risk PC and those with an LE of less than 5 years and high-risk PC,” the authors advised. “Despite the strong role of LE in treatment guidelines, patients with limited LE have historically been overtreated for indolent cancer”. Among 96,032 men with PC in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Medicare database, we found that 52% of men older than 65 years had an LE of less than 10 years, and during the early 2000s, more than half of these men with an LE of less than 10 years were treated aggressively with surgery or radiotherapy for low-risk and intermediate-risk disease, mainly with radiotherapy.

“With increasing use of active surveillance for low-risk and some intermediate-risk PCs, there is a question as to whether overtreatment of men with limited LE has persisted in the active surveillance era.”

The study found it notable that such overtreatment exists in a non–fee-for-service setting such as the VA, which has been a national leader in reducing overtreatment based on disease risk, explaining that “suggests that the problem of overtreatment of men with limited LE has not been solved in the active surveillance era, despite increasing numbers of men with low-risk PC receiving active surveillance.”

Two types of overtreatment were discussed — overly aggressive treatment of men with tumors with low oncologic risk and in patients with limited LE who are unlikely to benefit from treatment.

The report offered several explanations, including the difficulty of clinical integration of prediction tools, which has led some physicians to frequently omit or overgeneralize discussions of life expectancy in consultations. In addition, the authors noted, physicians often feel that patients do not want to discuss LE, “although we found this to be untrue among most men with PC”.

They also pointed to “social pressures for physicians to intervene in the setting of potentially lethal cancer may nudge clinicians toward treatment, despite a poor long-term risk/reward balance.”

In addition, medico legal concerns exist regarding the potential for negative oncologic outcomes with conservative management, which might motivate physicians to be risk-averse for higher-grade cancers. The researchers said they recently published data showing no such successful lawsuits, however.

The study team further acknowledged that it was not surprising that most of the overtreatment involved radiotherapy and not radical prostatectomy, since most of the patients have multiple comorbidities and are not candidates for surgery. “Yet, this observation is critical to targeting interventions to curtail such overtreatment, and urologists and radiation oncologists need to play active roles in this effort,” the authors added.

Urologists are often the first clinicians to counsel men and might have an opportunity to assess LE and recommend against further specialty consultations, workups, or treatment at the time of initial counseling, according to the article.

After referral, the researchers added, “it is critical that radiation oncologists independently assess longevity and the appropriateness of treatment and not just assume that a referral indicates a mandate for treatment.”

They said previous research found that radiation oncologists spend less time discussing LE and competing risks than urologists and medical oncologists, explaining, “This may owe to radiation oncologists assuming that the competing risks of mortality vs other-cause mortality have already been discussed by the urologist and that referral indicates the urologist’s tacit approval of definitive treatment. Yet, if the radiation oncologist were to independently assess LE and the appropriateness of care, it would provide another opportunity to reduce overtreatment.”

Based on previous findings that information on life expectancy is often omitted in patient consultations or generalized as high or low, the authors proposed a communication strategy called the trifecta method, in which a clinician should (1) quote the risk of the cancer mortality (2) with and without treatment (3) at the patient’s LE.

“This approach integrates risk of the cancer and the benefit of treatment and quotes prognostic information at the most relevant point: the patient’s expected lifetime,” they explained. “Because patients and physicians appear to be more focused on cancer mortality, this approach ensures that LE is integrated in assessments of cancer risk and treatment benefit; for example, even a higher-risk tumor would pose little threat to a patient with limited LE if the risk is posed at their expected longevity.”

- Daskivich TJ, Luu M, Heard J, Thomas I, Leppert JT. Overtreatment of Prostate Cancer Among Men With Limited Longevity in the Active Surveillance Era. JAMA Intern Med. Published online November 11, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.5994