WASHINGTON, DC—A recently launched VA study of mortality in Vietnam veterans will examine whether exposure to liver flukes, a parasitic worm, increased the risk of cholangiocarcinoma or bile duct cancer in those veterans.

The study comes on the heels of research conducted at the Northport, NY, VAMC, which showed that 24% of Vietnam veterans who ate raw or undercooked fish while deployed in Southeast Asia tested positive or borderline positive for prior worm infection.1

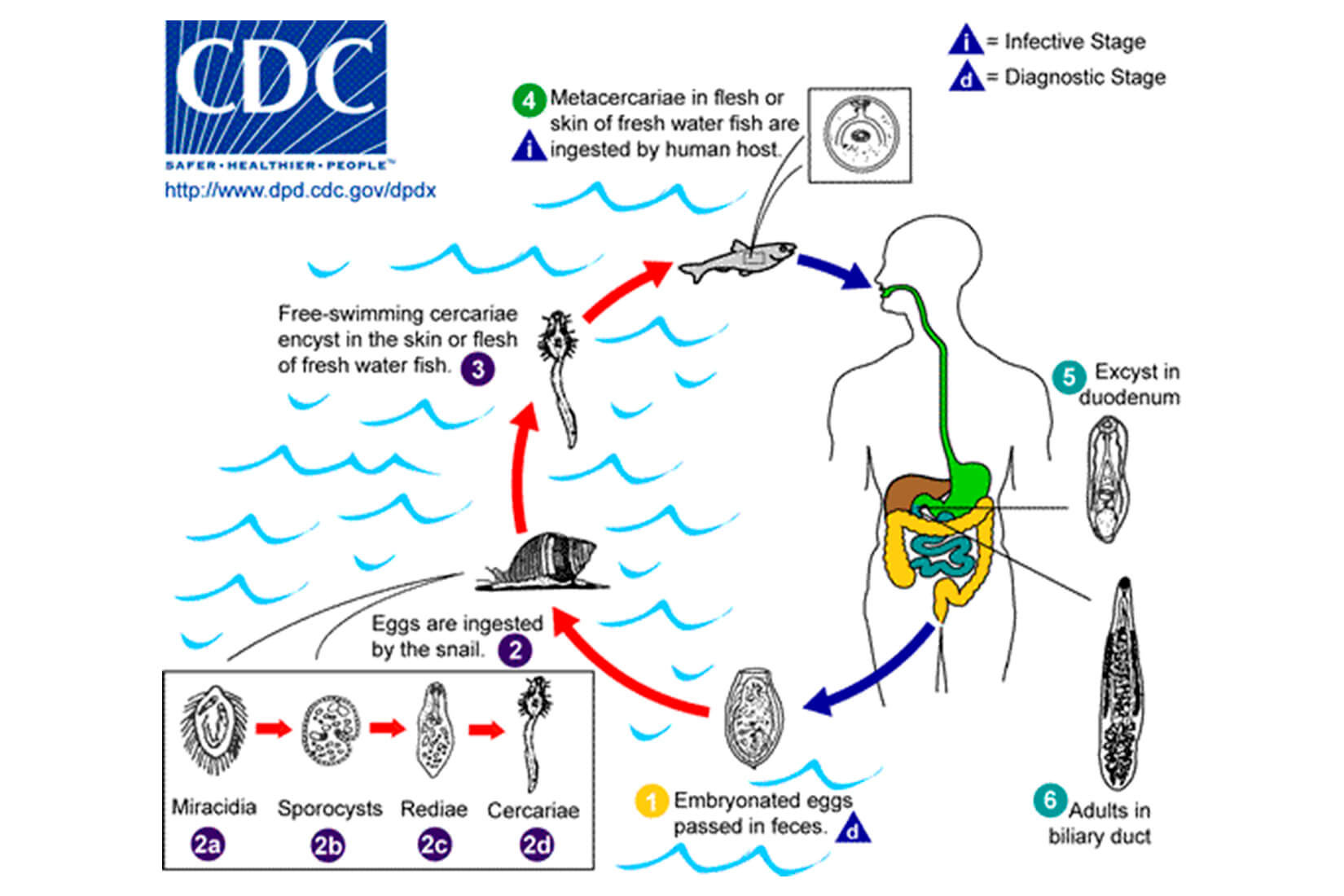

Infection with two species of liver fluke, which is common in Asia, is a known risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma. The bile duct cancer is relatively rare in the United States, with about 8,000 cases per year, according to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Northport study indicating a potential association between service in Vietnam and bile duct cancer generated significant interest from legislators, veterans’ groups and the media, but many of the reports ignored the significant caveats expressed by the researchers. A panel of infectious disease experts also raised questions about methodological issues in the study.

Cholangiocarcinoma generally occurs in individuals in their 60s. Risk factors other than liver flukes include primary sclerosing cholangitis, cysts in the bile ducts, cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis B or C virus, diabetes, obesity and genetic factors.2

“Over the past 15 years, of about 1.4 million Vietnam-era veterans who had VA healthcare, 845 veterans have a diagnosis of hepatic duct or biliary duct cancer or cholangiocarcinoma as determined by a review of VA medical records for the appropriate diagnosis codes,” VA spokeswoman Ndidi Mojay told U.S. Medicine.

That rate does not appear to indicate that Vietnam veterans are at greater risk of developing the cancer, according to the VA. “Our examination of VA medical records doesn’t show an excess of veterans with cholangiocarcinoma among the set of veterans who are of the age to have been in Vietnam and who had cholangiocarcinoma. Further, VA is not aware of any studies that show that bile duct cancer occurs more often in U.S. Vietnam War veterans than in other groups of people,” Mojay said.

VA Epidemiologic Study

To provide a definitive answer about any link between liver fluke exposure and cholangiocarcinoma risk, the VA has undertaken a large-scale epidemiologic study. Results of the study are expected in 18 months to two years.

In the study, “VA will gather the numbers of bile duct cancer-related deaths of Vietnam-era veterans from 1979 through 2015. Results from this research will inform VA of the scope of the problem and allow VA to compare mortality among veterans with service in the Vietnam War to those who served elsewhere during that timeframe,” explained former VA Secretary David Shulkin, MD, in a letter to Rep. Lee Zeldin (R-NY).

The Northport research team, led by George Psevdos, MD, screened 97 veterans who served in Vietnam and identified 50 who reported exposure to raw or undercooked fish. The researchers sent blood specimens from the 50 veterans to the Seoul National University College of Medicine in South Korea for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing using an antigen that tested for a number of parasitic worms. The assay included Clonorchis sinensis, a liver fluke common in northern Vietnam, China and Korea. The assay did not include Opisthorchis viverrini, the liver fluke found in southern Vietnam, Thailand and Laos. There is no commercially available test for C. sinensis in the U.S. and a specific O. viverrini antigen has not yet been developed.

Twelve of the blood samples tested positive for exposure to C. sinensis. None of the men with positive tests had current liver fluke infection. One veteran had an Entamoeba histolytica infection. None of those with positive results had abnormal findings in the extrahepatic or intrahepatic bile ducts on imaging with either computed tomography or ultrasound, according to the results.

The one veteran in the study with a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma had negative results for liver fluke exposure in two tests. In response, the researchers suggested that the time lag since possible exposure and the patient’s weakened immune system as a result of chemotherapy might have made the antibodies undetectable in this patient.

The study team was more confident in the testing results for the other veterans. “Because our veterans served in the area where Opisthorchis species were prevalent, they might have been infected by O. viverrini and not by C. sinensis,” the researchers said. “We can estimate that the 12 ELISA positive Veterans were likely exposed to O. viverrini because the 2 liver flukes share common antigens that can cross react with each other. Cross reaction with other helminthic antigens is also possible.”

The study provides “evidence of exposure to the liver fluke parasites in U.S. soldiers during their service in the Vietnam War,” the authors wrote, recommending a larger epidemiological study using a specific O. viverrini antigen and comparing liver fluke-exposed and unexposed veterans.

Experts from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, as well as the VA, took exception to the researcher’s conclusions in a letter to the editor in the same issue of Infectious Disease in Clinical Practice.3

In their letter, the authors said that the Northport researchers’ conclusion “may potentially overstate the strength of their findings,” as a result of a number of methodological issues. They pointed out that the extent to which cross reactivity between Clonorchis can detect Opishorchis antibodies is unknown, as is the extent to which cross reactivity detects other helminth antibodies. They also noted that the lack of positive and negative controls in the study made it “difficult to conclude whether the positive results are more likely to represent true prior infections or false positives.”

Even if veterans were exposed to liver flukes during their service, “the risk of complications, such as cholangiocarcinoma, is likely related to the intensity of the fluke infection, which in infected veterans may have been low compared with endemic populations who may regularly consume undercooked or raw fish,” according to the editorialists. They noted that Southeast Asian immigrants to the U.S. diagnosed with O. viverrini and C. sinensis infections rarely develop cholangiocarcinoma.

Still, the correspondents agreed with the Northport researchers that development of a sensitive and specific assay for O. viverrini and other flukes “would enhance our ability to measure the past and current risk of these parasites to veterans and active military personnel.”

The VA’s Office of Research and Development and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science are discussing a research project to develop such an assay, according to Mojay.

The editorialists said they recognized that the Northport study addressed a health concern of Vietnam veterans but maintained it did not provide sufficient evidence to change current clinical practice. Instead, they urged clinicians to “educate concerned patients as to their low risk of cholangiocarcinoma and also discuss other more common causes of liver cancer including the viruses hepatitis B and C.”

1. Psevdos G, Ford FM, Sung-Tae H. Screening US Vietnam Veterans for Liver Fluke Exposure 5 Decades After the End of the War. Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. July 2018;26(4):208-210.

2. Yao KJ, Jabbour S, Parekh N, Lin Y, Moss RA. Increasing mortality in the United States from cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Database. BMC Gastroenterology. 2016;16:117.

3. Nash TE, Sullivan D, Mitre E, et al. Comments on “Screening US Vietnam Veterans for Liver Fluke Expsoure 5 Decades After the End of the War.” Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. July 2018;26(4):240.