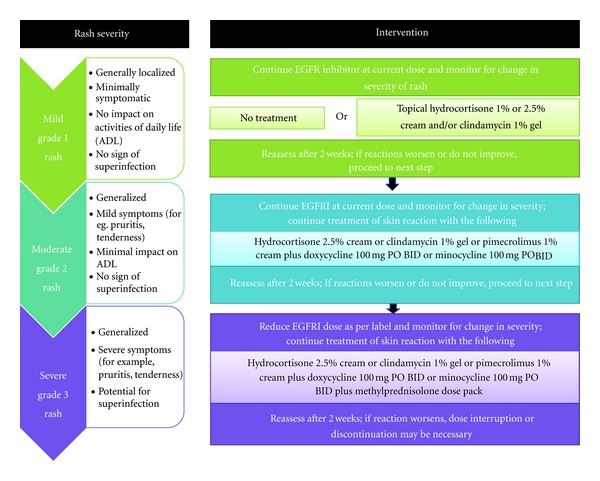

Click to Enlarge: Treatment recommendations for EGFRI-associated rash. Adapted from Lynch et al. 2007. Source: Hindawi

NEW YORK — Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors such as panitumumab are pivotal in treating metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients with wild-type KRAS mutations in the first, second and third lines, especially in patients with wild-type RAS genes. Unlike other targeted therapies used in CRC, such as VEGF inhibitors, which can cause hypertension, proteinuria, and gastrointestinal perforations, EGFR inhibitors are unique in their high incidence of dermatologic toxicities.

These cutaneous side effects stem from the inhibition of EGFR signaling in the skin. Because EGFR plays a crucial role in the regulation of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, blocking this pathway disrupts normal skin homeostasis. The affected skin may also release cytokines, which then attract neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes to the area, leading to an inflammatory response that presents as a papulopustular rash.

While dermatological toxicities are not fatal, they can profoundly affect patients’ comfort, social engagement and willingness to continue therapy at the recommended dose, making prevention and treatment vital to effective care and positive outcomes.

On the plus side, the rash commonly arising from EGFR inhibitor (EGFRI) therapy has been associated with objective tumor response and longer patient survival, making appropriate treatment of these potentially disfiguring dermatologic responses even more important.1

Studies indicate that most patients experience some form of skin reaction, with approximately 10% to 20% encountering severe (grade 3) toxicities. Severe reactions are more common with combinations of EGFRs and chemotherapy, such as 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), as recommended in first- and second-line regimens, and lead to dose modificationsor interruptions in about 30% of affected patients.2

The most common manifestation is a papulopustular (acneiform) rash, typically emerging within the first two weeks of therapy. This rash predominantly affects areas rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face, scalp, upper chest, and back, and is characterized by pruritic and tender erythematous papules and pustules. Other dermatologic side effects include xerosis, pruritus, paronychia, ocular conditions and hair changes such as trichomegaly and alopecia, which may emerge a few weeks to a few months after treatment initiation. Skin reactions are transient and subside at the conclusion of therapy.

Preventive measures

“The proper patient education and understanding of the potential dermatological side effects from EGFRI is the essential cornerstone of its management,” said Shaad Abdullah and colleagues at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “At the start of EGFRI treatment, the clinicians should inform their patients of potential EGFRI-related symptoms of dermatologic toxicities and possible lifestyle changes that may enhance their comfort.”

While no clinical trials have established the best course of treatment for EGFR inhibitor-related rashes and other dermatological responses, several groups have developed recommendations since the use of the drugs began.

Early, preventive care is widely recommended. Reactive management of dermatologic toxicities often occurs too late to significantly reduce their impact, making prophylactic care important in successful in development of successful treatment algorithms for patients being treat with EGFR inhibitors for metastatic CRC.3

Proactive management include maintaining a structured skincare regimen, using gentle cleansers and thick alcohol-free emollients to preserve skin hydration, and applying broad-spectrum sunscreens with high SPF to protect against exacerbation by sun exposure. Long, hot showers should be avoided, as should any agents likely to dry out the skin such as alcohol, benzoyl peroxide or retin A products. Additionally, prophylactic use of topical steroids and oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline or minocycline, has been shown to reduce the incidence and severity of rashes.

The STEPP trial demonstrated that preemptive treatment for the first six weeks of panitumumab plus chemotherapy significantly reduced the incidence of grade 2 or higher dermatological toxicities.4

In the study, patients applied a moisturizer over the body every morning, used sunscreen before going outdoors, and applied topical 1% hydrocortisone cream to the face, hands, feet, neck, back and chest each evening. Participants also took oral doxycycline twice a day. Investigators could also provide reactive treatment, as needed.

Among patients who received prophylactic treatment, the incidence of grade 2 or higher skin toxicities was 29% vs. 62% in the group that received only reactive care (odds ratio, 0.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1–0.6). Grade 3 or 4 toxicities also were far less likely in the preemptively treated group, 6% vs. 21% for the reactively treated group. The preemptively treated group also had longer median progression-free survival, 4.7 months vs. 4.1% (hazard ratio [HR], 1.0; 95% CI, 0.6–1.6).

The J-STEPP trial showed similar results.5

Once dermatologic toxicities develop, tailored interventions based on severity are crucial. For mild-to-moderate cases (grade 1 or 2), continuation of the recommendations for prophylactic care is appropriate. Antihistimines will reduce pruritis. For grade 3 or 4 cases, the addition of topical corticosteroids and/or topical antibiotics can help manage rash and prevent superinfection; oral antibiotics may also be required. Patient continuation of topical emollients and moisturizers is also important.6

Dermatologic toxicities are a common and significant concern in patients receiving EGFR inhibitors for mCRC. Through proactive prevention, effective management strategies, and patient education, healthcare providers can enhance patient comfort, adherence to therapy, and overall treatment outcomes, according to study authors.

- Abdullah SE, Haigentz M Jr, Piperdi B. Dermatologic Toxicities from Monoclonal Antibodies and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors against EGFR: Pathophysiology and Management. Chemother Res Pract. 2012;2012:351210. doi: 10.1155/2012/351210. Epub 2012 Sep 11. PMID: 22997576; PMCID: PMC3446637.

- DeStefano LM, Perrone M, Andrews S, et al. Dermatologic Toxicity Occurring During Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Inhibitor Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18(1):e9-e23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29576427/

- Hofheinz RD, Deplanque G, Komatsu Y, Kobayashi Y, Ocvirk J, Racca P, Guenther S, Zhang J, Lacouture ME, Jatoi A. Recommendations for the Prophylactic Management of Skin Reactions Induced by Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors in Patients With Solid Tumors. Oncologist. 2016 Dec;21(12):1483-1491.

- Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, et al. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-emptive skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:1351–7.

- Kobayashi Y, Komatsu Y, Yuki S, et al. Randomized controlled trial on the skin toxicity of panitumumab in Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: HGCSG1001 study; J-STEPP. Future Oncol 2015; 11:617–27.

- Lacouture ME, Anadkat M, Jatoi A, Garawin T, Bohac C, Mitchell E. Dermatologic Toxicity Occurring During Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Inhibitor Therapy in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018 Jun;17(2):85-96. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.12.004. Epub 2017 Dec 13.