Catherine Mezzacappa, MD Research Fellow Yale School of Medicine and VA Connecticut Healthcare System

West Haven, CT — Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common blood-borne pathogen in the United States, with HCV-related cirrhosis being the leading cause of primary liver cancer, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). For that reason, regular HCC screening has been recommended for HCV patients who have developed cirrhosis.

With the advent of improved HVC treatments and the aging of the baby boomers—who make up the majority of affected HCV patients but also have the greatest risk of comorbid medical conditions that might attenuate the benefit of HCC screening—researchers including Catherine Mezzacappa, MD, have questioned, however, whether HCC screening in patients successfully treated for HCV is still associated with improved survival.

As the nation’s largest provider of liver-related health care and hepatitis C treatment, the VA was the right place to ask—and answer—that question, reasoned Mezzacappa, a research fellow at Yale School of Medicine and VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Along with her mentor, Tamar H. Taddei, MD, and other VA collaborators including David E. Kaplan, MD, of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC and the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, both in Philadelphia, Mezzacappa sought answers in a cohort of VA patients developed by Taddei and Kaplan. The cohort consisted of 16,902 people with HCV-associated cirrhosis who achieved HCV cure after treatment with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs in the VA healthcare system between January 2014 and December 2022.

DAAs are a relatively new class of oral medications that inhibit specific HCV nonstructural proteins that are vital for the virus’s replication. A short course of treatment (typically 12 weeks) can achieve a virologic cure for almost all treated patients, the researchers noted in JAMA Network Open.1

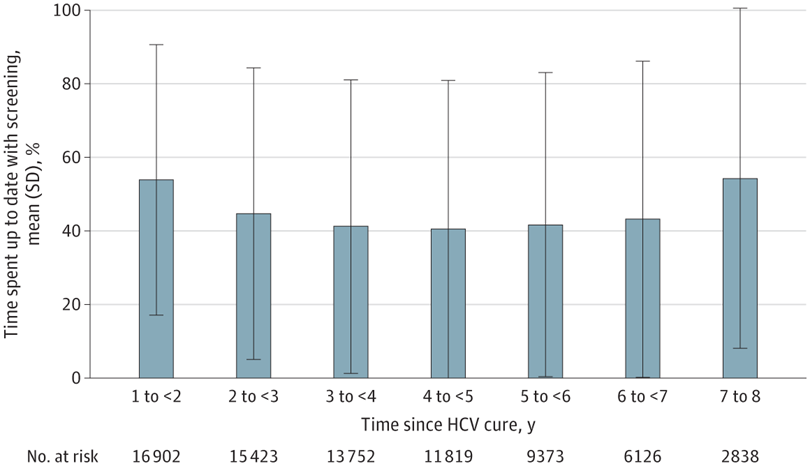

The researchers calculated the percentage of time spent up to date with recommended screening by year of follow-up and during the 4 years preceding HCC diagnosis. “So we said, ‘OK, after your virus is cured, what proportion of time are you up to date with getting your screening exams, and if you go onto to develop liver cancer, does being up-to-date for a greater amount of time improve your survival after being diagnosed with cancer?’” Mezzacappa told U.S. Medicine. “And we found that it did.”

Of the cohort, approximately one-tenth (1,622) developed HCC over the study period. The cumulative incidence of HCC declined from 2.4% (409 of 16,902 individuals) to 1.0% (27 of 2833 individuals) from Year 1 to Year 7 of follow-up. Being up-to-date with screening for at least 50% of the time during the 4 years preceding HCC diagnosis was associated with improved overall survival. In multivariate analysis, each 10% increase in follow-up spent up to date with screening was associated with a 3.2% decrease in the hazard of death.

Click to Enlarge: Mean Percentage of Time Eligible Participants Remained Up to Date With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening by Year Since Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Cure. Source: JAMA Network Open

There was a statistically significant interaction between time since HCV cure and screening, with no association observed among those who received a diagnosis of HCC more than 5 years after HCV cure. Each 10% of time spent up to date with screening was associated with a 10.1% increased likelihood of diagnosis with early-stage HCC and a 6.8% increased likelihood of curative treatment.

On average, Mezzacappa said, 40 to 50% of the cohort were up-to-date on their screenings—a percentage that is significantly higher than has been found in private sector healthcare, but not as high as she would like, considering the study’s findings of its effectiveness. Also, the percentages of those up to date dropped off over time, suggesting that once their liver disease gets better people stop thinking about it, she said.

For physicians treating patients who have a history of hepatitis C infection, Mezzacappa said the study provides two important messages. The first is, “Think about whether that patient has liver cirrhosis because that would mean they should be getting liver cancer screening even though their virus is eliminated,” she said, adding cirrhosis can be silent, and it’s not going to be apparent “unless you look for it.”

“The second point is that patients, even if they are getting older, if they remain in overall good enough health that you think they would be able to undergo treatment for a cancer, it is beneficial for at least 5 years, probably longer, after cure of the hepatitis c virus to continue to screen for liver cancer improve mortality,” she said.

Mezzacappa urged patients and physicians to be mindful of the risk of the cancer that remains even when the virus itself has successfully been treated. “Even after the virus is treated, don’t forget about the liver disease that is already there,” she emphasized.

- Mezzacappa C, Kim NJ, Vutien P, Kaplan DE, et. Al. Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Survival in Patients With Cirrhosis After Hepatitis C Virus Cure. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2420963. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.20963