LOS ANGELES—Epilepsy is substantially more common in veterans than the general population and, in up to 40% of them, anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) fail to control their seizures.

Veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have particularly elevated rates, largely because of the high rate of traumatic brain injury associated with blast exposures, according to the VA. The VA also notes that ‘due to the common diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans and the poor recognition of epilepsy, unknown numbers of Vietnam veterans are also experiencing seizures.’

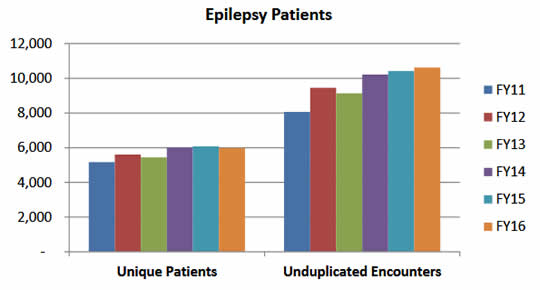

To meet the needs of these veterans, the VA has responded by offering more options for specialized care, particularly through the 16 Epilepsy Centers of Excellence established across the country, and leading research on epilepsy management and treatment.

A team from the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, led by Sunita Dergalust, PharmD, recently presented results of a study on drug-resistant focal epilepsy at the American Epilepsy Society. They found that found veterans with more than one type of seizure, more than two seizures a month and a history of traumatic brain injury had significantly increased risk of drug-resistant epilepsy.1

Further, while the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defines drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) as ‘failure of adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used anti-epileptic drug (AED) schedules to achieve sustained seizure freedom,’ the Los Angeles team determined that the most veterans with DRE have tried and continue to take many more medications.

Their study reviewed charts of veterans with epilepsy between the ages of 18 and 75 who were seen in the Seizure Clinic at the West LA VA Medical Center. Of 300 patients with focal onset epilepsy, 100 met the ILAE definition of drug resistance. More than half (55%) had experienced traumatic brain injury and had seizures at least twice a month. All DRE patients had at least two kinds of seizures. These veterans had tried and failed a mean of 5.22 anti-epileptic medications and continued to take an average of 3.22 drugs to help control their seizures.

Focal onset seizures or focal seizures were previously called partial seizures because the electrical disturbance that triggers them starts in and usually affects just one lobe or hemisphere of the brain. Patients may be awake and aware or they may be confused and have impaired awareness. Other symptoms vary depending on the part of the brain affected, but may include a strong sense of déjà vu, numbness or tingling, hallucinations or visual disturbances, intense emotions, unusual smells or tastes, feeling a ‘wave’ going through the head or stiffness or twitching in the extremities, according to the Epilepsy Society.

About 13.8 of 1,000 veterans have epilepsy, and most of them have the focal variety, Dergalust told U.S. Medicine. In the overall U.S. population, the prevalence is about 5 per 1,000 individuals.

‘In general, 30-40% of patients with epilepsy are medically refractory and account for 80% of the cost of treatment in the US. Drug resistance is probably more common in focal epilepsy than other forms of epilepsy,’ she said.

While patients with DRE do not get complete relief from seizures with anti-epileptic drugs, in some cases taking multiple medications can help control seizures, Dergalust noted.

‘Our goal in the management of epilepsy is no seizures and no side effects as soon as possible. It is not uncommon to have patients to try multiple AEDs before we can get the right combination that will help control the seizures and also minimize side effects,’ she explained.

Patients with DRE should also pay attention to lifestyle choice that can reduce their risk of seizures, Durgalust said. Those include compliance with their drug regimen, avoiding stressful situations and seizure triggers such as binge drinking, drug abuse and sleep deprivation. They should also avoid activities that can lower the threshold for seizures such as playing video games or use of stimulants.

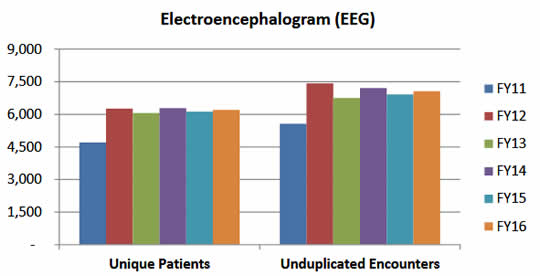

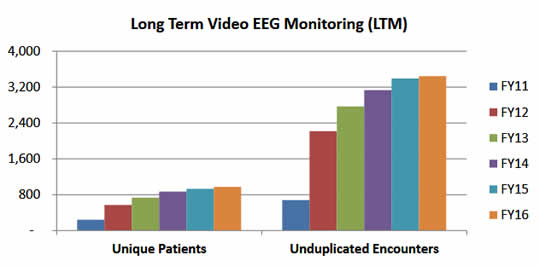

If anti-epileptics and seizure risk-reduction strategies do not provide relief, veterans may be referred to one of the Epilepsy Centers of Excellence, which are staffed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of epileptologists, neurosurgeons, neuroradiologists, therapists, psychiatrists, neurology pharmacists and nurses trained in the management of veterans with epilepsy.

‘These centers have the ability to closely monitor patients with the telemetry units and therefore offer different options to veterans who are resistant to multiple AEDs,’ said Durgalust. ‘This involves optimization of the patient’s AED regimens, surgical interventions, vagus nerve stimulation, Neuropace, ketogenic diet and enrollment in clinical trials of newer and experimental AEDs.’ Neuropace is an implanted neurostimulation system that detects and immediately disrupts abnormal electrical activity in the brain, functioning much like a pacemaker does for the heart.

The Epilepsy Centers of Excellence are also linked to Polytrauma Centers to collaboratively treat veterans who have moderate and severe traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic epilepsy.

Currently, veterans in the Los Angeles area have an additional resource to help manage drug-resistant epilepsy. ‘We are the only accredited pharmacy training program in neurology in the country, but we hope that this will be expanded to other VAMCs in the future’ Durgalust said. ‘Our services have improved patient care for those with neurological disorders and more specifically, we have improved compliance and seizure control in veterans with medically refractory epilepsy.’

1Aramian AM, Chae HJ, Crossley A, Wen M, Nguyen VH, Dergalust S. Predicting Drug Resistance in Veterans with Focal Epilepsy. American Epilepsy Society 2017 Annual Meeting. Abst. 3.291.