CTE Had Been Widely Accepted as Issue in Military Personnel

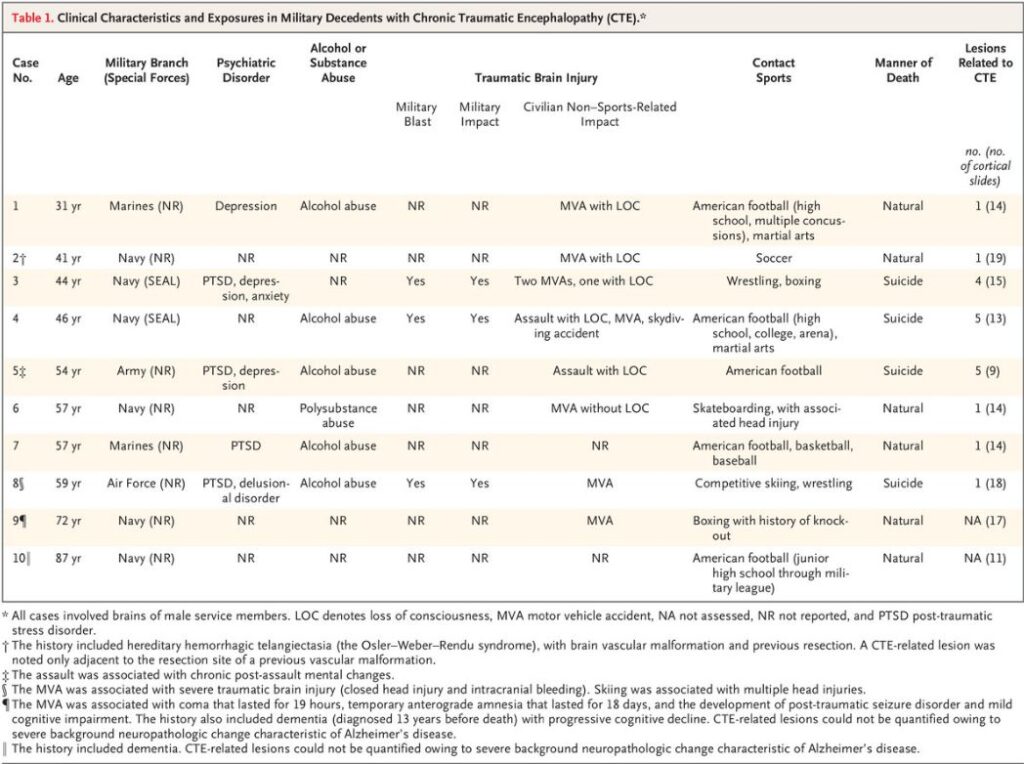

Click To Enlarge: Clinical Characteristics and Exposures in Military Decedents with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Source: New England Journal of Medicine

BETHESDA, MD — Military personnel exposed to attacks with high explosives frequently experience neuropsychiatric symptoms, including cognitive dysfunction, behavioral changes, mood disturbances and suicidality. The similarity between many of these symptoms and those of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)—a degenerative brain disease primarily seen in athletes with a history of repetitive head trauma due to impact—has led to the suggestion that military service, and blast exposure specifically, is associated with CTE.

A new study of brain tissue from deceased servicemembers shows, however, that CTE in the population is actually quite low and, when it does occur, it may not be related to blasts at all. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.1

To better understand a potential link between blast exposure and CTE, researchers at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, examined 225 brains at the university’s Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine (CNRM) Brain Tissue Repository. “CTE has very specific alterations in the brain that can be identified under a microscope,” said Daniel Perl, MD, who leads the repository. Perl and his colleagues used those criteria on the brain specimens to see how many fit the diagnosis of CTE—a diagnosis that can be made only after death.

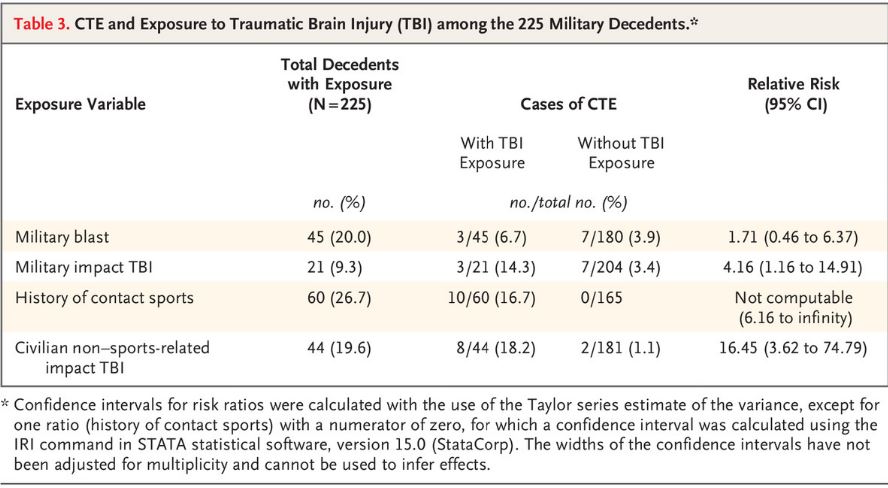

Click To Enlarge: CTE and Exposure to Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) among the 225 Military Decedents. Source: New England Journal of Medicine

“Basically what we found was the CTE was rather rare among servicemembers and, when we did find it, the extent of involvement of the brain was really very mild—barely a diagnosis,” he told U.S. Medicine.

Specifically, neuropathological findings of CTE were present in 10 of the 225 brains (4.4%) examined; half the CTE cases had only a single pathogenomonic lesion.

Once the researchers found and evaluated those 10 cases, they reviewed their histories, based in part on interviews with family members, and found that all 10 had not only been in the military, but had also participated in contact sports, Perl said.

Other specific findings of the study included:

- Of the 45 brains from decedents who had a history of blast exposure, 3 had CTE, as compared with 7 of 180 brains from those without a history of blast exposure.

- Three of 21 brains from decedents with traumatic brain injury from an injury during military service caused by the head striking a physical object without associated blast exposure had CTE, as compared with 7 of 204 without this exposure.

- CTE was present in 8 of 44 brains from decedents with non–sports-related traumatic brain injuries in civilian life, as compared with 2 of 181 brains from those without such exposure in civilian life.

The researchers also found that many of the prominent symptoms seen after deployment that have been associated with CTE—PTSD, alcohol and drug abuse and death by suicide—did not correlate to a diagnosis of CTE.

Perl said he was less surprised by the low rate of CTE the study found that he was by “the rather widespread acceptance that CTE was causing all of these problems, even though it was very little data on which to base that belief.”

“When you look at it, CTE develops long after individuals have had their head injury,” he said. “Look at NFL football players. By and large, they don’t develop the disease until 10, 15, or 20 years after they have retired. Our servicemembers were symptomatic when they returned from deployment—a much quicker time period, so that didn’t fit with what we understand CTE to be like.”

Completely Different From Blast Damage

Despite the infrequency of CTE in the brains studied, that doesn’t necessarily the brains were normal, Perl said. Studies—including those by Perl and his colleagues—have shown that blast does damage the brain, but it damages it in completely different ways than impact does. “The brains were not necessary normal, but to suggest that the problem is related to CTE, to that disease, appears to be incorrect,” he said.

Perl also cautioned against extrapolating the data to the population in general. “This is a convenience sample,” he said. “Although 225 brains is a lot of brains, it is still a small component of the population as a whole.”

Nevertheless, the study gives some idea of the relative frequency of CTE in the general population “There really had not been a study like this of young, active males in the population. This is the first one, and we could only find 4.4 percent of individuals in this cohort that the diagnosis was CTE,” said Perl. “I think it says something about the civilian population, the general population, the non-NFL player population. One of the overall risk of going through life as a young male is developing this disease, and it would appear that is relatively uncommon.”

He said the connection between blast exposure and CTE development is one that should continue to be explored. “The blast exposure was dramatic during the war against terror in the Middle East. The people that were part of the study were primarily from that era and are relatively young,” he said. “Because CTE develops long after the exposure, it is possible that it could show up in veterans later. Obviously, we don’t know what is going to happen. We have to continue to study this and see whether that wave who have been exposed in the way develop this problem as they get older, but so far we haven’t seen it.”

- Priemer DS, Iacono D, Rhodes CH, Olsen CH, Perl DP. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in the Brains of Military Personnel. N Engl J Med. 2022 Jun 9;386(23):2169-2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203199. PMID: 35675177.