As part of the celebration of U.S. Medicine’s 60th anniversary, we are profiling some of the remarkable achievements in federal medicine over the past six decades. In the fourth of that series, we interviewed David B. Ross, MD, PhD, director of the VA’s HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Program, about the VA’s success in virtually eliminating chronic hepatitis C among veterans. The interview has been slightly edited for clarity and brevity.

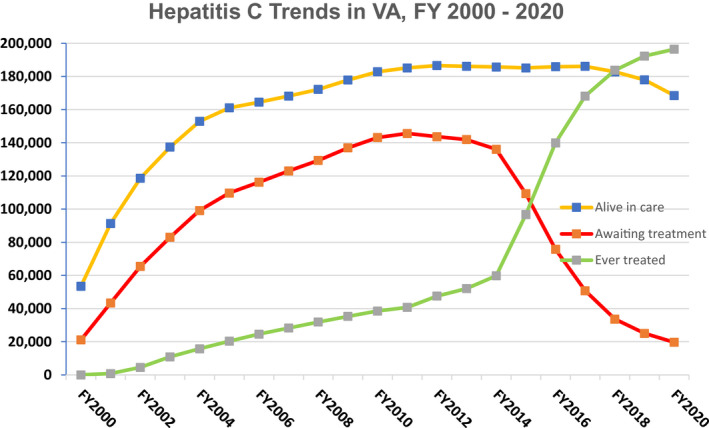

Click to Enlarge: Number of Veterans in care at VA facilities (yellow line), the number of Veterans awaiting HCV treatment (red line), and the number of Veterans ever treated for hepatitis C (green line), between fiscal year FY 2000 and FY 2020. Source: VA Hepatitis C Cube. Source: Clinical Liver Disease

WASHINGTON, DC — In the early 2000s, the VA recognized it had a serious problem. Recent research indicated that veterans were three times more likely to be infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) than the general population, and Vietnam veterans—the largest cohort in care—bore the brunt of those infections. In response, the VA established a comprehensive national HCV program, a decision that positioned the agency to achieve an extraordinary victory in public health.

The challenges the VA faced were not for the faint of heart. An aggressive screening program diagnosed more than 180,000 veterans receiving care through the VA with HCV by 2010. Few patients could tolerate the interferon-based treatment for the 48 weeks required, and fewer were cured. Better tolerated and more effective options came online over the next few years, but interferon remained a challenging component.

In 2014, the first oral direct-acting antiviral (DAA) without interferon received FDA approval. It offered a better than 90% cure rate, but it was expensive. Very expensive. And the VA had a lot of veterans to treat. So, it started treating veterans with cirrhosis or other signs of advanced liver disease, then the VA made a decision that put it in the forefront of the battle against HCV.

USM: What was the calculation for the VA in deciding to commit to treating every veteran with HCV in the system, given the huge numbers and projected high cost?

Ross: Treating every veteran with HCV is simply the right thing to do. VA announced in March 2016 that it would expand treatment availability to all veterans in VA care diagnosed with HCV, not just those with advanced liver disease (ALD). VA hepatitis C providers, facility directors and directors of VHA’s veterans Integrated System Networks (VISNs) enthusiastically supported this announcement for several reasons.

[Those involved in the decision knew that] rates of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cirrhosis of the liver and liver failure were skyrocketing among veterans in VA care with HCV. VA data and research showed that cure of HCV decreased death from all causes—not just liver disease—among all veterans with HCV, not just those with ALD.

In addition, the new direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) were much more effective (cure rates up to 95%) and much less toxic than standard treatments. They also shortened the time needed for treatment from 12 months of injections and pills to as little as eight weeks of taking one pill a day.

At the time, veterans in VA care living with HCV were 50 to 70 years old. If VA was going to do something to help these veterans, it had to do something now.

USM: For months, in some cases years, after VA’s decision to treat any veteran with chronic HCV, state Medicaid programs, Medicare and commercial insurers restricted treatment to a subset of those with advanced liver disease. How did the unique features of VA healthcare make the decision to expand treatment possible and prudent?

Ross: VA was the only healthcare organization in the U.S. with the structures and processes in place and the familiarity with HCV to diagnose, link to care, treat and cure more than 100,000 patients with this disease in such a short time.

VA’s accomplishments in this therapeutic area were due to the existing cadre of clinicians (both MD and non-MD) with enormous experience in diagnosing and treating HCV patients and equally enormous passion for treating and curing veterans with HCV as soon as possible. We also had a large cadre of VHA subject-matter experts on HCV who willingly contributed their time and expertise to construct a systemwide approach and develop population health management methods appropriate to the size of the undertaking.

The VA had already identified risk factors for HCV specific to veterans in VA care, including Vietnam War-era service, and had already screened two-thirds of the veterans in VA care for HCV by the time the DAAs became available. It also adopted reflex HCV testing to distinguish chronic HCV infection from HCV exposure. In addition, access to state-of-the-art molecular laboratory testing within VHA allowed providers in all VISNs to confirm HCV diagnoses, determine which strain (genotype) of HCV a veteran had, monitor the effectiveness of treatment and confirm cure.

The four Hepatitis C Resource Centers had been operating for more than a decade, disseminating best practices in diagnosis and treatment and providing education for veterans and providers. We had integrated HCV care with treatment for alcohol-use disorder, substance-use disorder and mental health conditions (an approach pioneered by VHA) that would otherwise be high barriers to HCV treatment.

Very close collaboration between clinicians and VHA’s Pharmacy Benefit Management Office at the VHA, VISN and VA Medical Center levels along with a uniform VA national formulary standardized therapy. The extremely experienced and well-trained clinical pharmacists throughout VHA, with close interaction and collaboration between clinical pharmacists and other HCV clinicians at all VA Medical Centers, streamlined treatment.

Nationally, we benefited from interactive, systemwide coordination and communication by VHA’s National Viral Hepatitis Program and its National Hepatitis C Resource Center along with strong support by VA and VHA senior leadership.

USM: What was sacrificed to reach the VA’s goal for HCV treatment in terms of diversion of funds, staff and attention?

Ross: While this goal required major efforts from our staff at all levels, no resources were diverted or clinical needs were neglected or sacrificed. The key was redesigning VHA’s HCV care systems to improve access, quality and value.

Each VISN stood up an HCV Innovation Team (HIT), with each HIT charged with analyzing HCV care across their VISN, identifying gaps in diagnosis, linkage to care and treatment and developing and implementing ways of bridging those gaps.

This effort was coordinated by VA’s National Hepatitis C Resource Center, led by Timothy Morgan, MD, chief of hepatology at the Long Beach VAMC; Rachel Gonzalez, MPH, former assistant director, VA National Hepatic Consortium for Redesigning Care; and Angela Park, PharmD, VA’s Office of Healthcare Transformation, who co-led the Hepatitis C Innovation Team National Collaborative.

To make the program as efficient and as effective as possible, VHA-wide standard guidelines for diagnosis and treatment were developed and hundreds of non-MD providers, such as nurse practitioners and clinical pharmacists, were trained along with primary care physicians to treat patients for hepatitis C, with cure rates similar to those achieved by liver disease specialists.

USM: How has the success been maintained as new veterans have come into care?

Ross: New cases of hepatitis C are being diagnosed among veterans in VA care because of the opioid-use pandemic and injection drug use. VA is addressing this new challenge by making harm reduction services available at all VA healthcare facilities to prevent new hepatitis C cases as well as diagnose, link to care and treat veterans who have acquired hepatitis C.

In addition, VA has expanded its use of population health clinical dashboards, allowing VA front-line providers to rapidly identify veterans who haven’t been tested yet for HCV, those who could benefit from repeat testing and those who have already been diagnosed with hepatitis C but have not yet been treated. These dashboards allow VA clinicians to reach out to these veterans and offer them HCV testing and treatment, as well as referral for substance use disorder or mental health treatment services, if needed.

- HCV Elimination in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2021 Aug 18;18(1):1-6. doi: 10.1002/cld.1150. PMID: 34484696; PMCID: PMC8405054.