ATLANTA — Marked racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-associated morbidity and mortality have raised important questions about racial and ethnic differences associated with other respiratory viral infections, including influenza. Annual flu epidemics result in 140,000 to 810,000 hospitalizations and 12,000 to 61,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.

While prior research has shown that pandemic influenza outbreaks are likely to disproportionately affect socially disadvantaged people in the United States, comprehensive data on racial and ethnic differences in rates of influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States are lacking, explained lead author Alissa O’Halloran, MSPH, an epidemiologist in the CDC’s Influenza Division.

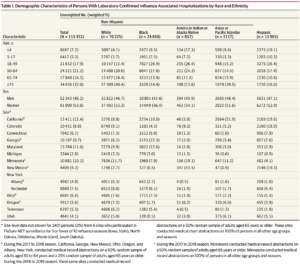

To describe racial and ethnic differences in flu-related ICU admissions and in-hospital death, O’Halloran and colleagues at university and VAMCs and public health departments across the United States conducted a cross-sectional study using data from the Influenza-Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET).

The network conducts population-based surveillance for laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in selected counties, representing approximately 9% of the U.S. population.1

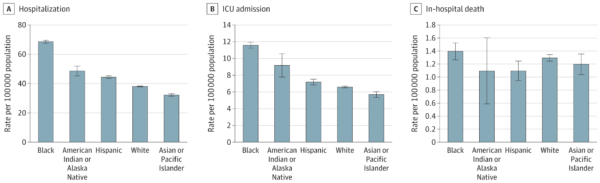

The researchers, including representatives from the Atlanta VAMC, analyzed influenza data for hospitalizations from the 2009 to 2010 season to the 2018 to 2019 season. The main outcomes were age-adjusted and age-stratified rates of influenza-associated hospitalization, ICU admission, and in-hospital death by race and ethnicity overall and by influenza season.

They found that generally, across every season, rates of hospitalization and ICU admission were higher among non-Hispanic Black patients compared with non-Hispanic white patients. But for other racial and ethnic groups, they didn’t see that same level of consistency across seasons, O’Halloran said. “When we looked at racial and ethnic differences by state, we did see that rates in Hispanic or Latino persons and American Indian or Alaska Native persons were primarily driven by certain states,” she advised. “Higher rates in certain seasons within racial and ethnic groups may have in part been due to geographic outbreaks in those areas during those seasons.”

The most surprising finding, O’Halloran said, was that differences in rates of hospitalization, ICU admission and in-hospital death by race and ethnicity were greatest in children 0-4 years (up to 4 times higher) and declined with increasing age. “In fact, there were few differences in rates of severe influenza-associated outcomes in adults 75 years and older across racial/ethnic groups,” she said.

Underserved Populations

Prior studies have shown that people living in high poverty areas were at higher risk of severe outcomes from flu, suggesting that socioeconomic status may be associated with higher flu-related hospitalization rates among these groups, said O’Halloran. Other social determinants of health such as disparities in healthcare, lower influenza vaccination coverage, and crowded housing among racial and ethnic minority groups also might contribute.

“Clinical implications of studies like this will most likely be represented by increases in investments aimed to close the gap in racial and ethnic disparities in severe flu outcomes,” said O’Halloran, adding that improving vaccine access, acceptance and confidence can help.

Because people of color might be at higher risk for getting flu or developing serious illness, resulting in hospitalization, flu vaccination is especially important for these communities, public health officials have emphasized. CDC recommends that everyone 6 months and older, with rare exceptions, get a seasonal flu vaccine each year, ideally by the end of October.

To increase vaccination rates, CDC is providing additional funding to state immunization programs to plan and implement flu vaccination programs for the 2021-2022 flu season, with a focus on priority groups, including non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic or Latino populations, O’Halloran said. CDC is also working to increase vaccination rates among ethnic and racial minority communities by engaging with partners and developing customized outreach to racial and ethnic minority communities to increase flu vaccination rates this year and every year, including developing culturally specific messaging and tailored content to reach additional audiences.

A new CDC grant program, Partnering for Vaccine Equality, recognizes that the most effective solutions to increasing access, acceptance and confidence will ultimately come from within communities. “Outreach and education activities in partnership with communities empower leaders and other trusted messengers to share vaccine facts and science about the importance of vaccination through culturally appropriate messages and build bridges between communities and vaccination providers in a way that fosters trust and confidence while vaccinating against vaccine myths and misinformation,” she said. “Community-driven engagement lets leaders who know their communities best, make the recommendations—allowing for a more personalized, effective, and sustainable approach.”

- O’Halloran AC, Holstein R, Cummings C, Kirley PD, Alden NB Yousey-Hindes K, Anderson EJ , Ryan P , Kim S, Lynfield R , McMullen C, Bennett NM, Spina N, Billing LM, Sutton M, Schaffner W, Talbot HK, Price A, Fry AM, Reed C, Garg S. Rates of Influenza-Associated Hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit Admission, and In-Hospital Death by Race and Ethnicity in the United States From 2009 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Aug 2; 4(8). doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21880