Click to Enlarge: CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate solution; CRE, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales; ICU, intensive care unit; MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. *National random sample.

Source: American Journal of Infection Control

TEMPLE, TX — Microbial contamination—including pathogenic and potentially pathogenic bacteria—persisted on high-touch hospital surfaces despite compliance with recommended disinfection protocols, according to a study performed at the Central Texas Veterans Healthcare System.

A report published in the American Journal of Infection Control (AJIC) underscored the difficulties involved in eliminating healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). The VA-led study suggested that innovative strategies might be necessary for more-effective disinfection of these surfaces.1

Guidelines and protocols call for established disinfection procedures to keep patients and healthcare workers safe from the risk of microbial contamination on hospital surfaces, which plays a major role in the spread of HAIs.

The new study demonstrated, however, that current best practices in routine hospital disinfection simply might not be sufficient to prevent the spread of pathogens. That especially could be the case for surfaces that many different people frequently touch.

At the Central Texas VAMC facilities, the researchers collected samples from 400 surfaces between June and July of 2022. The focus was on high-touch surfaces such as simulation manikins used for resuscitation practice, workstations on wheels, breakroom tables, bedrails and computer Y-boards at nurses’ stations. They found that all of the surfaces harbor bacteria, with manikins and bedrails also having the most diverse types of bacteria.

The study team cultured the samples using replicate organism detection and counting (RODAC) Tryptic Soy agar plates. Colonies were then subcultured to blood agar plates and speciated using MALDI-TOF. The local microbiology laboratory database was queried for any clinical isolate match with the environmental samples recovered.

Ultimately, 60 different kinds of bacteria were identified across all samples, including 18 well-known human pathogens; many of those can be pathogenic to humans under certain circumstances. The most common types of known pathogenic bacteria included Enterococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella aerogenes, among others.

Those bacteria can lead to central-line associated bloodstream infections, meningitis and endocarditis. The authors noted that about half of the bacteria identified through sampling also were found in clinical samples collected from patients during 2022.

The clinical microbiology laboratory identified 29 of 60 hospital surface bacteria in clinical isolates and determined that urine, soft tissue and blood were the most common sources of clinical isolates.

“It is a continuing frustration to healthcare professionals that HAIs persist despite rigorous attention to disinfection practices,” explained senior author Piyali Chatterjee, PhD, a research scientist at Central Texas Veterans Healthcare System. “Our study clearly shows the bioburden associated with high-touch hospital surfaces—including simulation manikins, which are not typically regarded as a risk, because patients rarely touch them—and indicates that we must do better in protecting the health of our patients and our hospital employees.”

“Surfaces in the health care environment harbor both well-known and not-so-well-known human pathogens,” the authors concluded. “Several not-so-well-known pathogens are skin flora or environmental bacteria, which in the right setting, can become pathogenic and cause diseases including meningitis, brain abscess, endocarditis, and bacteremia.”

The situation could be even worse in non-VA hospitals, with a recent study in the American Journal of Infection Control suggesting that VA facilities generally do a better job in infection prevention for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE).2

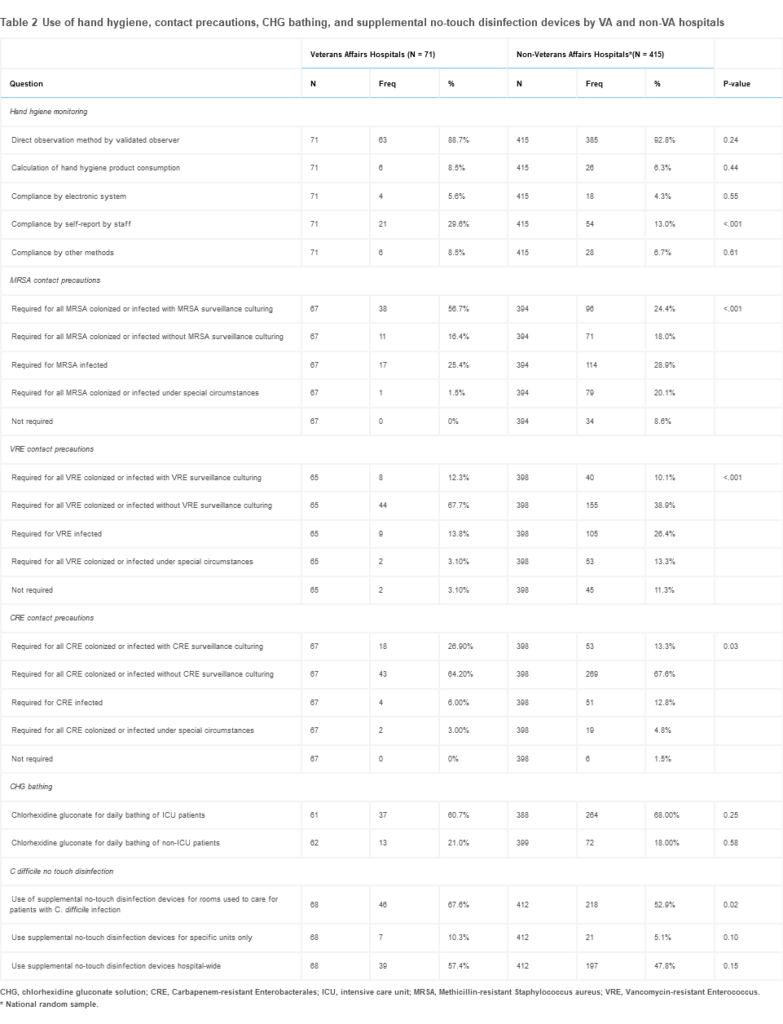

Data were collected via a survey conducted from April 2021 to May 2022 sent to infection preventionists at all 127 VA hospitals and a random sample of 881 U.S. non-VA hospitals about hospital and infection control program characteristics and various infection-transmission-focused prevention practices.

“This national survey of U.S. hospitals demonstrated variability in how VA and non-VA hospitals employed infection prevention strategies to reduce disease transmission,” according to the authors from the University of Michigan Medical School, the LTC Charles S Kettles VAMC, both in Ann Arbor, MI, and colleagues. “We found VA hospitals were more likely to use contact precautions for MRSA, VRE, and CRE than non-VA hospitals, and a higher percentage of VA hospitals reported use of supplemental no-touch disinfection devices for environmental room cleaning for patients with C difficile infection.”

The use of contact precautions for MRSA, VRE and CRE varied, with VA hospitals generally more likely to deploy contact precaution requirements for all three multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). As an integrated system, some infection prevention activities are implemented nationally across VA hospitals, such as the MRSA prevention initiative.

The initiative was first instituted in 2007 and included universal surveillance for MRSA colonization and contact precautions for patients identified as MRSA carriers.

In addition, a higher percentage of VA facilities reported using no-touch disinfection devices for the prevention of C difficile. Although studies demonstrate that certain technologies can inactivate C difficile spores, current expert recommendations identify the use of touchless disinfection technology as an unresolved issue.

- Jinadatha C, Navarathna T, Negron-Diaz J, Ghamande G, et. Al. Understanding the significance of microbiota recovered from health care surfaces. Am J Infect Control. 2023 Nov 28:S0196-6553(23)00785-X. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2023.11.006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38206212.

- Scruggs-Wodkowski E, Greene MT, Saint S, Fowler KE, Linder KA, Krein SL. Comparing practices to prevent infectious diseases transmission among Veterans Affairs and Nonveterans Affairs hospitals: Results from a national survey in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2023 Nov 7:S0196-6553(23)00767-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2023.10.013. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37944756.