Earlier this year, somewhere in the Adriatic Sea, Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class Lauren Kestell (left), administered a COVID-19 booster to Chief Fire Controlman (AEGIS). Kellen Smothers aboard Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Mitscher. Booster uptake has lagged in both the military and the VA, according to recent reports. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Daniel Serianni

SAN FRANCISCO — President Joe Biden, despite being 79 years old, had a mild case of COVID-19. The primary explanation for why he escaped severe symptoms is that he was not only vaccinated, but double-boosted.

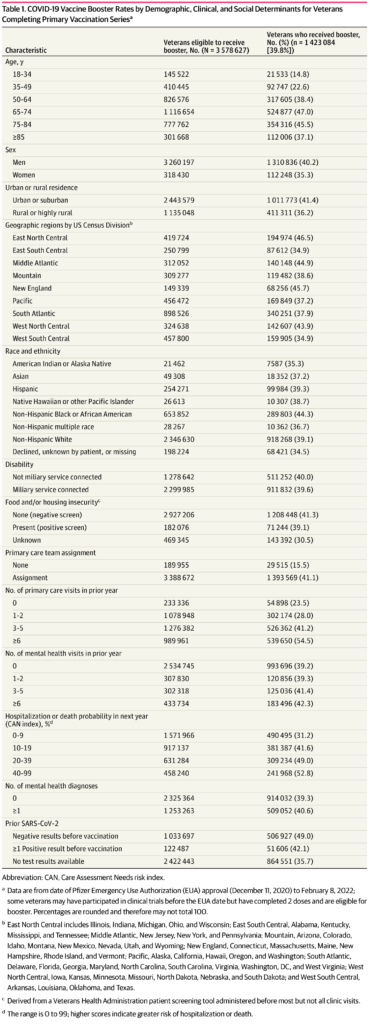

Most VHA patients are not in that situation, however. Only 64% completed primary COVID-19 vaccination, making them eligible to receive a booster. Of those eligible, the rate of receiving an initial booster is lower than 40%, according to a new study led by the San Francisco Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System.1

The article in JAMA Network Open pointed out that “vaccination markedly decreases serious illness, hospitalization, and mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but immunity wanes, leaving individuals susceptible to COVID-19. Thus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend vaccine boosters. Some subpopulations have lower rates of primary COVID-19 vaccination than others, suggesting that increasing numbers of individuals will lack protection against COVID-19 should booster-eligible individuals fail to receive boosters.”

Specifically, the authors report that, of about 6.2 million veterans enrolled in the VHA, nearly 4 million completed primary COVID-19 vaccination and were eligible to receive a booster. The study team sought to determine the association of demographic, clinical and social determinants of health with COVID-19 booster completion; the goal was to identify vulnerable subpopulations.

Click To Enlarge: COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Rates by Demographic, Clinical, and Social Determinants for Veterans Completing Primary Vaccination Series Source: Jama Network Open

Researchers used the VHA electronic health record (EHR) to create a retrospective cohort of 3,578,627 veterans from Dec.11, 2020, when the first Emergency Use Authorization approval was granted by the Food and Drug Administration, and the first COVID-19 vaccinations were administered at the VA, through Feb. 8, 2022. The participants had a mean age of 65.9, with 8.8% women and 91.2% men. Most, 65.6% were non-Hispanic white, with 0.6% American Indian or Alaska Native, 1.4% Asian, 7.1% Hispanic, 0.7% Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, 18.3% non-Hispanic Black or African American, 0.8% were of multiple non-Hispanic races and 5.5% unknown race or ethnicity.

Defined as the primary outcome was receipt of the first COVID-19 booster after primary vaccination within or outside the VHA, as denoted in the EHR.

Results indicate that, of the eligible VHA enrollees, 1,423,084 enrollees (39.8%) received a booster. The lowest booster rates were among veterans aged 18 to 34 years, according to the study.

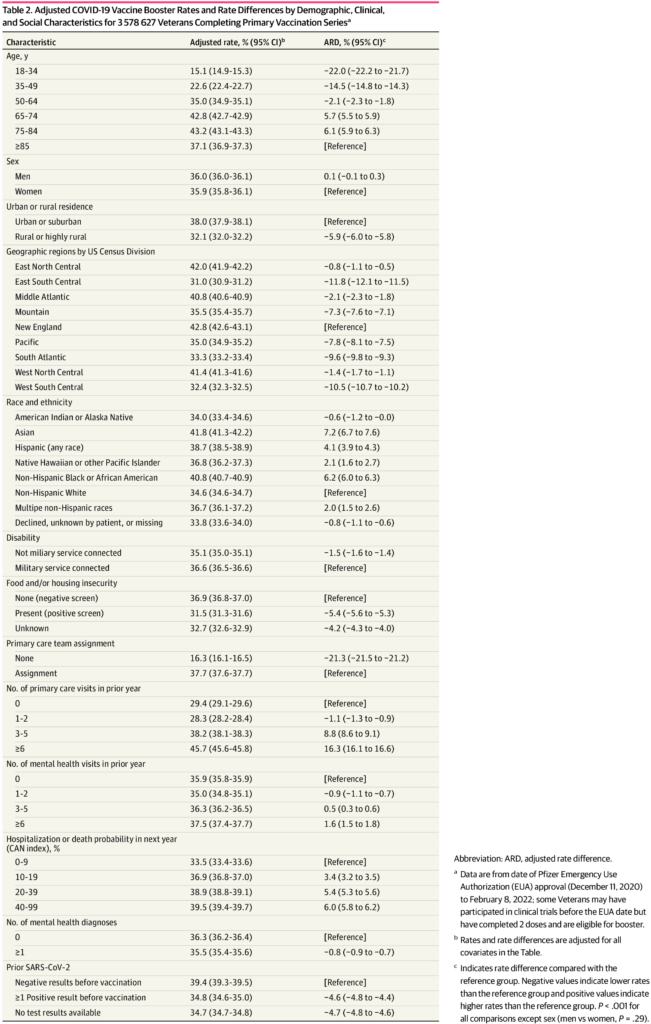

Veterans less likely to receive boosters included those:

- Not assigned vs assigned a primary care team,

- With rural vs urban residence, and

- Reporting housing and/or food insecurity versus not.

The authors also noted that veterans from the East South Central region had the lowest rates compared with those from New England, which were used as a reference group. In addition, Black or African-American veterans had the highest booster rates (44.3%); while American Indian or Alaska Native veterans had the lowest (35.4%).

Less Than Half

“This cohort study found that less than half of eligible U.S. veterans have received a COVID-19 vaccination booster,” the researchers advised. “Low booster rates in a population with primary vaccination is concerning; combined with those never vaccinated, millions are susceptible to COVID-19–related illness, hospitalization, and mortality. At greatest risk are veterans who are younger, are from American Indian or Alaska Native populations, reside in the South or in rural areas, are not assigned a primary care team, and report housing and/or food insecurity.”

The authors noted that their results in veterans were somewhat contrary to other studies, explaining, “Whereas Black and African American individuals in the general population are less likely to be vaccinated, the opposite occurred in the VHA because the VHA system has fewer barriers to access. Therefore, these results may not generalize to nonveteran populations, and the VHA EHR may not capture all community-administered boosters. Nevertheless, the VHA serves more than 6 million U.S. residents each year.”

The study team urged more outreach to younger, rural, American Indian or Alaska Native and homeless populations. It also encouraged primary care clinicians to discuss COVID-19 vaccination with unvaccinated and unboosted patients, saying that could help resolve disparities.

Click To Enlarge: Adjusted COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Rates and Rate Differences by Demographic, Clinical, and Social Characteristics for 3 578 627 Veterans Completing Primary Vaccination Series Source: Jama Network Open

A study earlier this year, also involving researchers from the San Francisco VA, explained why boosters were so important in the veteran population.

The report in Science discussed COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against infection (VE-I) and death (VE-D) by vaccine type in 780,225 VHA patients.2

“From February to October 2021, VE-I declined for all vaccine types, and the decline was greatest for the Janssen vaccine, resulting in a VE-I of 13.1%,” the authors wrote. “Although breakthrough infection increased risk of death, vaccination remained protective against death in persons who became infected during the Delta variant surge. From July to October 2021, VE-D for age <65 years was 73.0% for Janssen, 81.5% for Moderna, and 84.3% for Pfizer-BioNTech; VE-D for age ≥65 years was 52.2% for Janssen, 75.5% for Moderna, and 70.1% for Pfizer-BioNTech. Findings support continued efforts to increase vaccination, booster campaigns, and multiple additional layers of protection against infection.”

COVID-19 booster vaccine uptake also appeared to be lagging among the military, where only the original series was required. As of Jan. 31, only 24% of active-duty service members who were eligible for a booster had voluntarily received the additional shot, according to the DoD. Booster doses are not broken out on the DoD’s website, although they are included in the cumulative total.

- Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Manuel JK, Pyne JM. Association of Demographic, Clinical, and Social Determinants of Health With COVID-19 Vaccination Booster Dose Completion Among US Veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2222635. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.22635

- Cohn BA, Cirillo PM, Murphy CC, Krigbaum NY, Wallace AW. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine protection and deaths among US veterans during 2021. Science. 2022 Jan 21;375(6578):331-336. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0620. Epub 2021 Nov 4. PMID: 34735261.