As part of the celebration of U.S. Medicine’s 60th anniversary, we are profiling some of the remarkable achievements in federal medicine over the last six decades. In the fifth of that series, we interviewed Lynn Levin, MD, formerly of the Department of Epidemiology, Division of Preventive Medicine, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, about the research that led to the discovery of the crucial role of the Epstein-Barr virus in the development of multiple sclerosis and several other autoimmune disorders.

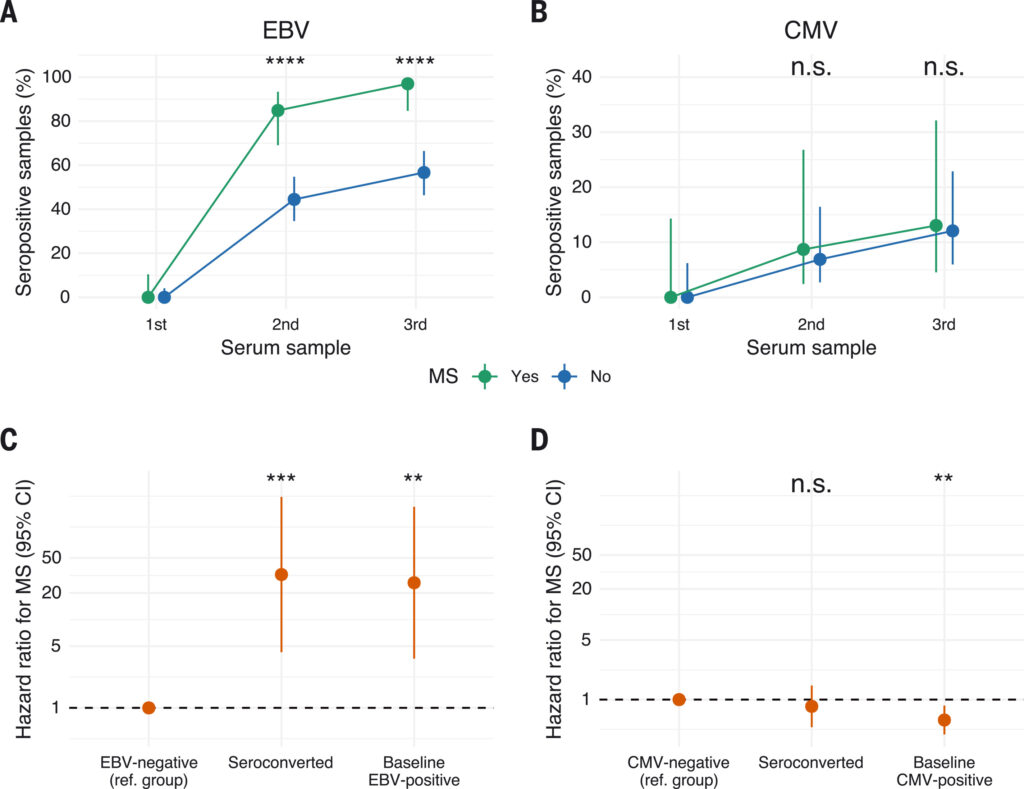

Click to Enlarge: EBV infection precedes MS onset and is associated with markedly higher disease risk.

(A) Proportion of individuals who were EBV-positive at the time of the first, second, and third sample. The figure is restricted to those who were EBV-negative at baseline and with EBV measurement in three samples (33 of 35 MS patients and 90 of 107 controls). A significantly higher proportion of individuals who later developed MS were EBV-positive in the second (28 of 33 MS patients) and third (32 of 33 MS patients) sample, compared with individuals who did not develop MS (second sample: 40 of 90 controls; third sample: 51 of 90 controls). ****P < 0.0001, two-sided Fisher’s exact test. (B) Proportion of individuals who were CMV-positive at the time of the first, second, and third sample collected in the study. The figure is restricted to those who were CMV- and EBV-negative at baseline. The proportion who were CMV-positive was similar in the second (two of 23 MS patients versus four of 60 controls) and third sample (three of 23 MS patients versus seven of 60 controls). All P > 0.05, two-sided Fisher’s exact test. (C) Risk ratio for MS according to EBV status. EBV seroconversion by the time of the third sample and EBV seropositivity at the time of the first sample were associated with a 32-fold and 26-fold increased risk of developing MS, respectively, in matched analyses. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, two-sided univariable conditional logistic regression model. (D) Risk ratio for MS according to CMV status. **P < 0.01, two-sided univariable conditional logistic regression model. Source: JAMA Network Open

SILVER SPRING, MD — In 2022, publication of a study in Science provided convincing evidence of a causal association between infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and development of multiple sclerosis (MS). Based on nearly 30 years of groundbreaking research, the study drew on several databases maintained by the DoD and utilized a study design developed by Lynn Levin, MD, a researcher at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research until her retirement in 2019.1

USM: Dr. Levin, this research reshaped our understanding of the relationship between Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. What inspired you to investigate this link?

Levin: A colleague I had worked with at Harvard approached me because of my background in study design for chronic conditions like MS, which really has no clear date of onset. I had worked on EBV and Hodgkin lymphoma with another Harvard researcher, so he knew I had done a lot of work on EBV as well. At the time, nobody thought MS had a viral component. I remember attending a meeting on EBV, and while people were open-minded, they thought it was a wild, far-fetched hypothesis.

USM: EBV is so widespread—about 95% of people are infected by adulthood—while MS is relatively rare. How did your study design overcome the challenges of investigating such a nuanced connection? What role did the DoD’s databases play?

Levin: In terms of designing a study, we could utilize already existing data; we didn’t have to start from scratch. We used existing military databases that were designed for other purposes but included the right kind of data to allow us to ask very important questions that probably could not have been answered anywhere else.

I knew that the Physical Disability Agency evaluates service members extensively when they are discharged due to medical conditions. If you have a disability, you get worked up by a lot of people so they can distinguish whether it’s MS or another autoimmune disease or a muscular problem. There’s a detailed narrative and the record provides a history from before an MS diagnosis like an eye problem or temporary blindness.

We could also pull serum from the Department of Defense Serum Repository (DoDSR) prior to the date of the first mention of symptoms. That repository was initially started to store serum collected as part of the HIV testing program [in 1989], but the organizers had the foresight to realize there could be other research uses for this repository. One of the researchers was able to figure out how to link the specimens in the repository to individuals in the military so that we could go back to the medical records associated with the samples and follow them over time.

Those two databases gave us really good, hard endpoints for the diagnosis and the first mention of symptoms, as well as prior EBV serology. That allowed us to look at the incidence or occurrence of the disease versus just the prevalence.

USM: At the time of the study in Science, the serum repository included samples for more than 10 million servicemembers, of whom 955 developed MS and 10 seroconverted prior to an MS diagnosis. In the JAMA article, you looked at samples from 3 million servicemembers, of whom three seroconverted during the study and prior to diagnosis. 2 How did that data strengthen the study and affect the findings?

Levin: So the challenge was that MS only affects about one in 1000 people, even though nearly everyone will contract EBV in their lifetime. While 99% of MS patients have had an EBV infection, 95% of those without MS have it, too, making it difficult to pin down the virus’s effects.

Establishing causality in epidemiology is incredibly challenging. You can’t randomly assign people to contract EBV and see who develops MS. In the article in JAMA, we showed it was likely a temporal sequence, that EBV came first. Some of these young guys were able to show that seroconversion, and that was really powerful.

The Science study confirmed EBV came first and showed a really strong relationship between EBV and MS. EBV infection increased the risk of developing MS more than 30-fold. We looked at other viruses, like [cytomegalovirus], and there was no relationship. The study was pretty specifically able to rule out just about any other viral infection.

USM: This research underscores the unique value of military medical data. Could this approach be applied to other diseases?

Levin: I think one of the most interesting parts of this story is that we utilized existing databases that were made for other purposes and yet were able to provide insight into a rare disease in young people. They offer a great resource that is so underutilized.

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, Kuhle J, Mina MJ, Leng Y, Elledge SJ, Niebuhr DW, Scher AI, Munger KL, Ascherio A. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022 Jan 21;375(6578):296-301.

- Levin LI, Munger KL, Rubertone MV, Peck CA, Lennette ET, Spiegelman D, Ascherio A. Temporal relationship between elevation of epstein-barr virus antibody titers and initial onset of neurological symptoms in multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2005 May 25;293(20):2496-500.