SEATTLE—For years, physicians have encouraged patients diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus to minimize or avoid drinking alcohol. But how much does it really matter?

“Controlled alcohol use over time, especially nonuse or very low-level use, is likely to help optimize health and longevity in people living with HIV,” said Emily C. Williams, PhD, MPS, a core investigator at the Center of Innovation for Veteran Centered and Value-Driven Care at the Puget Sound VAMC and associate professor in the department of health services at the University of Washington, both in Seattle.

Williams led a team of VA researchers who recently quantified the impact of changes in alcohol consumption on HIV disease severity in a study published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.1

The study evaluated changes in Veterans Aging Cohort Study Index 2.0 (VACS 2.0), a composite measure of HIV disease severity, associated with changes in Alcohol Use Identification Test Consumption scores in 23,297 veterans with HIV.

Overall, HIV disease severity improved slightly over time. The researchers found that veterans with relatively stable alcohol use had the greatest improvement. Counterintuitively, both significant increases and decreases in alcohol use worsened HIV severity, though increases had a slightly greater negative effect.

“While we found that those who increased drinking did worse overall than those who decreased, the reason for the deterioration in those who reduced drinking is not entirely clear,” Williams told U.S. Medicine. “We might be seeing the sickest people who are reducing drinking dramatically in response to illness or alcohol use disorder.”

AUDIT-C is a routine screen, and patients may want to report reduced drinking, regardless of actual change, Williams noted.

Errors in administration also might skew the results. “A clinician might say, ‘You don’t drink, do you?’ and mark zero,” she explained. “While we have confidence at the population level in AUDIT-C, we could be seeing some measurement bias here at the individual level.”

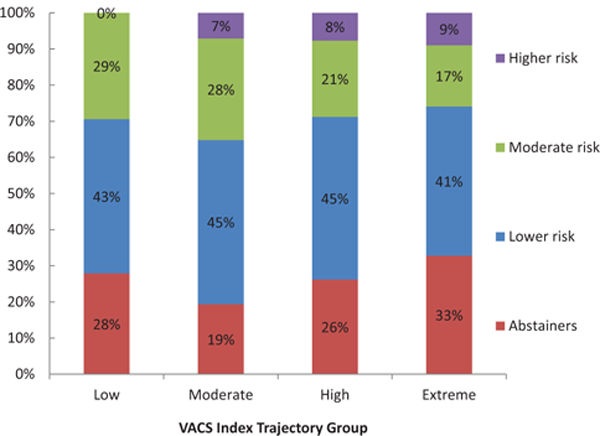

3359 HIV-infected participants in the VACS. AUDIT-C; alcohol use disorders identification test consumption; VACS, Veterans Aging Cohort Study Association between membership in VACS index score trajectory and AUDIT-C score trajectory was statistically significant (χ2 = 73, P < 0.001).

Source: Long-term alcohol use patterns and HIV disease severity. AIDS. 2017 Jun 1;31(9):1313-1321. doi: 10.1097/ QAD.0000000000001473. PubMed PMID: 28492393; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5596310.

No Alcohol for Most

Most of the veterans reported no alcohol use (51%) or lower level use (38%) at the initial screen. Low level alcohol use would be a score between 1 and 3 on the 12-point AUDIT-C for men or between 1 and 2 for women. Notably, 14% had a documented alcohol use disorder.

The subsequent AUDIT-C screen, administered nine to 15 months after the initial assessment, showed no change in drinking habits of 54% of the veterans, while 21% drank more, and 24% reported drinking less. Nearly all (97%) of the veterans with no change in drinking had initially reported no or low levels of alcohol consumption.

“We didn’t see much change in AUDIT-C over time, with most veterans staying at no or low-level drinking. That’s good news,” Williams said. “Some veterans had dramatic changes and those did the worst. Unstable drinking levels likely indicate someone on the spectrum of alcohol use disorder. While that’s a huge number, it’s not a huge proportion of veterans.”

Initial VACS Index 2.0 scores ranged from 0 to 134 on a scale of 0 to 164, with higher scores indicating greater disease severity and mortality risk. The mean score was 51.1.

VACS Index 2.0 calculates HIV disease severity using CD4 count, HIV-1 RNA levels, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, estimated liver fibrosis, hepatitis C infection, albumin levels, estimated glomerular filtration rate and body mass index. The average time between the first AUDIT-C screen and initial VACS Index 2.0 measurement was 8.1 days; the mean time between the second AUDIT-C screen and VACS Index 2.0 calculation was 10.4 days.

Changes in VACS Index 2.0 ranged from a decline of 65 to an improvement of 75 points. On average, patients improved 0.76 points. Veterans whose AUDIT-C scores moved by one point or less saw a VACS Index 2.0 improvement of 0.36 to 0.60 points. Veterans whose change in AUDIT-C scores indicated maximum increase in alcohol consumption (from 0 to 12) had a 3.74 point deterioration in VACS Index 2.0, while those who went from high use to no use (12 to 0) saw a slight worsening of 0.60 in VACS Index 2.0.

“Generally, VACS Index 2.0 scores don’t shift much,” Williams noted, “but changes of just five points are associated with a 20% increase in mortality risk. The changes seen here are not huge, but they are consistent.”

While VACS Index 2.0 scores generally rose with AUDIT-C risk, veterans with an AUDIT-C risk of zero had a higher VACS Index 2.0 than any but the highest risk AUDIT-C group.

“Patients with AUDIT-C score of 0 have increased risk for virtually everything,” Williams said. “It includes those who have stopped drinking because of illness as well as never drinkers.”

Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorder

While the changes seen in disease severity in this study are modest, “addressing alcohol use may be a key lever for optimizing health of people living with HIV and curbing the spread of the virus,” Williams added.

Despite the remarkable advances in treatment and life expectancy for those infected with the virus, HIV continues to spread. Social and behavioral factors play a significant role in disease trajectory and transmission, she noted.

“Alcohol use in particular both increases the risk of transmission and decreases the likelihood that people with HIV receive high-quality care for HIV, which is really the only way to suppress the virus and curb its spread,” Williams said.

To ensure veterans with HIV receive appropriate care, clinicians should adopt a tiered approach to assessing and offering treatment for alcohol use disorders.

“All patients with HIV should be screened for unhealthy alcohol use using validated instruments. Those screening positive should be offered brief counseling interventions and assessed for the most severe unhealthy alcohol use—alcohol use disorders. Those with alcohol use disorders should be offered effective pharmacotherapy and referral to specialty addictions treatment,” Williams recommended.

She noted that barriers to addiction treatment may make pharmacologic therapy the best choice for many patients. “Three medications are FDA approved to treat alcohol use disorders (acamprosate, disulfiram and naltrexone) and others (e.g., topiramate) have shown strong promise for treating alcohol use disorders.”

Clinicians should keep in mind that effective interventions to address alcohol use disorders exist, Williams added, “and thus HIV care providers may be able to play an additional role in curbing the spread of HIV by addressing alcohol use in people living with HIV.”

1. Williams EC, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, Matson TE, et. al. Ubinsky AD, Bobb JF, Lapham GT, HIV Disease Severity is Sensitive to Temporal Changes in Alcohol Use: A National Study of VA Patients with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019 Apr 15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002049. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 30973541.