ST. LOUIS — Thanks to the use of combination antiretroviral therapy, life expectancy is greater than it has ever been for people living with HIV/AIDS. But with that increase in life expectancy comes an increase in the number of non-AIDS-defining cancers.

Virally mediated cancers and cancers related to tobacco or alcohol use have a higher incidence in people with HIV and AIDS due to HIV-induced inflammation, immunodeficiency and high tobacco use in that population, said Angela L. Mazul, PhD, assistant professor of otolaryngology—head & neck surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the seventh-most-common cancer worldwide—and its incidence is rising. HNSCC is rapidly increasing in both people with HIV/AIDS and the general population due to a rise in oropharyngeal HNSCC associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV), Mazul said. Those with HIV/ AIDS have been found to have higher rates of incident HPV infection, but with lower rates of clearance than people who are HIV-negative. One study found that, among veterans living with HIV, oropharyngeal HNSCC incidence had increased from 6.8 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1996-2000 to 11.4 per 100,000 person-years in 2006-2009. This higher disease burden, combined with continually increasing numbers of people with HIV/AIDS, is culminating in increasingly common and complex interactions between HNSCC and HIV.

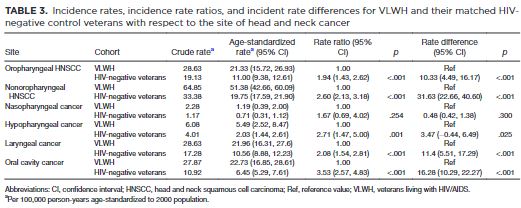

A new study by Mazul and her colleagues out of Michael E. DeBakey VAMC’s Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety is the first to estimate the effect of HIV versus HIV-negative veterans on the risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma incidence in a large retrospective cohort study. The study, which was published in the American Cancer Society journal Cancer, used patient data from 1999 to 2016 from the National Veterans Administration Corporate Data Warehouse and the VA Central Cancer Registry. The study included 45,052 veterans living with HIV/AIDS and 162,486 HIV-negative patients matched by age, sex and index visit (i.e., HIV diagnosis date or clinic visit date). 1

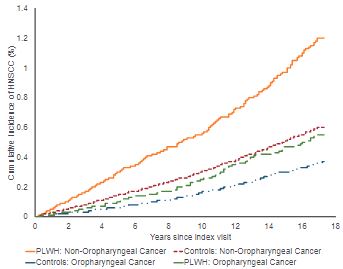

Click to Enlarge: Cumulative incidence of oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal cancer in veterans living with HIV (VLWH) and HIV-negative control veterans. Source: American Cancer Society

The age-standardized incidence rates were calculated, then estimated adjusted hazard ratios were calculated with a Cox proportional hazards regression for oropharyngeal and non-oropharyngeal HNSCC. The authors also abstracted HPV status from oropharyngeal HNSCC diagnosed after 2010.

Higher Rates of Cancer

“We found the people with HIV had higher rates of cancer than people without HIV,” said Mazul. Specifically, veterans living with HIV/AIDS have 1.71 times the risk of oropharyngeal cancer and 2.06 times the risk of non-oropharyngeal cancer compared with HIV-negative veterans, the study found. HIV-positive veterans with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) were more likely to be HPV-positive than were HIV-negative veterans with OPSCC, although this difference was not significant, the authors wrote. For non-oropharyngeal cancer, the increased risk of oral cavity cancer among VLWH drove the increased risk.

Further, cancer risk was lower for HIV-positive veterans with higher CD4 counts, suggesting that better control of HIV offers some protection for cancers, she added.

The study, which shed new light on the effect of HIV on head and neck cancer risk, was possible because of the VHA’s extensive medical records—which included information on smoking and HPV, the two main risk factors for head and neck cancers—as well as the universal access to care for the patients studied, said Mazul. “In the VA, theoretically everyone has the same access to care—to see the doctor, to afford going to the doctor,” Mazul pointed out. “For HIV this is relevant because being able to get the medication and stay on medication is important for your risk of cancer.”

Mazul said the study highlights both the need for control of HIV to reduce cancer risk as well as the importance of HPV vaccination in the veteran and, she adds, military populations.

“HPV vaccine it is pretty much the best way to prevent getting HPV-associated cancers,” said Mazul, adding that the vaccine is recommended for anyone under 26 and that those between 26 and 45 who have not been vaccinated should discuss the advisability of vaccination with a clinician.

Because of the high risk of head and neck cancer among veterans—with or without HIV—efforts for prevention and early detection in the VHA are important, Mazul said.

“[The veteran population] is a population where that is ‘intervenable’” said Mazul. “Everyone has equitable access to care. So theoretically we should be able to be sure that people with HIV adhere to treatment, but then people who don’t have HIV are able to seek care for their cancer or to say, ‘I have a sore in my mouth’ and to be able to see ENT who will be able to tell them if it is just an ulcer or if it’s cancer.”

- Mazul AL, Hartman CM, Mowery YM, Kramer JR, et. al. Risk and incidence of head and neck cancers in veterans living with HIV and matched HIV-negative veterans. Cancer. 2022 Sep 15;128(18):3310-3318. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34387. Epub 2022 Jul 22. PMID: 35867552.