Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer 10-Fold More Likely

SAN DIEGO — Already the second-leading cause of cancer death in the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is increasing in adults younger than 50. Early-age onset CRC (EAOCRC) is often diagnosed at later stages, which require more intense treatment, according to a new study.

Most, 70% to 95%, of patients with EAOCRC present with “red-flag” signs or symptoms that could be indicative of CRC, according to the report in JAMA Network Open, which pointed out that EAOCRC risk is elevated up to 10-fold among patients with a diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) or hematochezia.1

“Given the frequency of symptomatic EAOCRC presentation, more aggressive workup of adults younger than 50 years of age with these conditions may enhance timely diagnosis and treatment and ultimately improve EAOCRC outcomes,” wrote researchers from the VA San Diego Healthcare System, the University of California San Diego and colleagues.

The study team asked whether there was a variation in the diagnostic test completion rate and in the time to diagnostic workup among veterans younger than 50 years with IDA and/or hematochezia.

Results of the cohort study of veterans with IDA and/or hematochezia found that, overall, diagnostic testing rates were low. Furthermore, the authors advised that diagnostic testing was less likely among female, Black, and Hispanic veterans with IDA and Hispanic veterans with hematochezia.

“This study suggests that optimizing timely follow-up may help improve early age–onset colorectal cancer-related outcomes and reduce sex-based and race and ethnicity–based disparities,” they wrote.

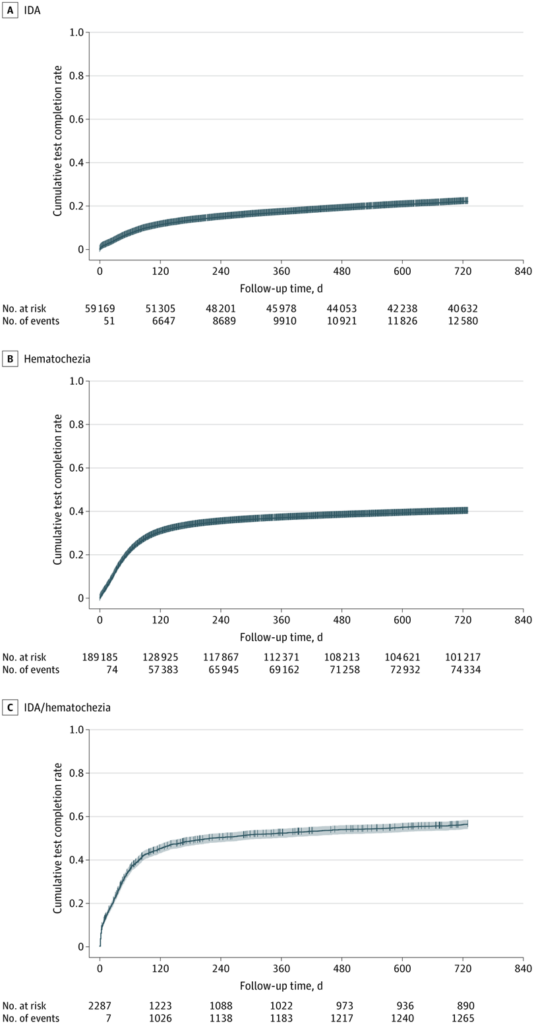

Pointing out that the diagnostic test completion rate and the time to diagnostic endoscopy or colonoscopy among adults with iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) and/or hematochezia were not well characterized, the researchers conducted the study between Oct.1, 1999, and Dec. 31, 2019, among U.S. veterans aged 18 to 49 years from two separate cohorts: 59,169 with a diagnosis of IDA and 189,185 with a diagnosis of hematochezia. Statistical analysis was conducted from August 2021 to August 2023.

Defined as the primary outcomes were receipt of bidirectional endoscopy after diagnosis of IDA and colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy after diagnosis of hematochezia.

Veterans with a diagnosis of IDA had a mean age of 40.7, while those with a diagnosis of hematochezia had a mean age of 39.4; the 2,287 veterans with both had a mean age of 41.6.

Results indicated that the cumulative 2-year diagnostic workup completion rate was 22% (95% CI, 22%-22%) among veterans with IDA and 40% (95% CI, 40%-40%) among veterans with hematochezia.

“Veterans with IDA were mostly aged 40 to 49 years (37 719 [63.7%]) and disproportionately Black (24 480 [41.4%]),” the researchers noted. “Women with IDA (rate ratio [RR], 0.42; 95% CI, 0.40-0.43) had a lower likelihood of diagnostic test completion compared with men with IDA. Black (RR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.68) and Hispanic (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.82-0.94) veterans with IDA were less likely to receive diagnostic testing compared with white veterans with IDA.”

The study explained that veterans with hematochezia were mostly white (105 341 [55.7%]), adding, “Among veterans with hematochezia, those aged 30 to 49 years were more likely to receive diagnostic testing than adults younger than 30 years of age (age 30-39 years: RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.12-1.18; age 40-49 years: RR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.33-1.40). Hispanic veterans with hematochezia were less likely to receive diagnostic testing compared with white veterans with hematochezia (RR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.93-0.98).”

Background information in the article cited published guidelines as recommending that all men and postmenopausal women with IDA undergo bidirectional endoscopy—both esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. “The American Gastroenterological Association updated their guidelines in 2020 to additionally recommend that otherwise asymptomatic premenopausal women (e.g., those without another explanation, such as menorrhagia) also receive bidirectional endoscopy,” the authors wrote. “Adults younger than 50 years of age with hematochezia without lower abdominal symptoms and no known source of bleeding are also recommended to undergo colonoscopy. However, the extent to which these guidelines are followed, and the variation in following guidelines across populations, has not been widely studied, to our knowledge.”

Likelihood of Workup

The study pointed out that receipt of diagnostic testing within 60 days of diagnosis of IDA or hematochezia occurred for only 7% of those with IDA and 22% of those with hematochezia, adding that, after IDA diagnosis, men were more likely to receive diagnostic testing compared with women, and the likelihood of workup increased with age. “After diagnosis of hematochezia, adults aged 30 to 49 years were more likely to receive diagnostic testing compared with adults younger than 30 years,” the researchers stated. “Black veterans were less likely to receive diagnostic testing after an IDA diagnosis, and Hispanic veterans were less likely to receive diagnostic testing after an IDA or hematochezia diagnosis, compared with White veterans. Given that both IDA and hematochezia have been shown to increase EAOCRC risk, our findings suggest that there are significant opportunities to improve EAOCRC outcomes, including sex-based and race and ethnicity-based disparities, by promoting diagnostic testing after IDA and hematochezia diagnosis.”

Although the risk of incident and fatal EAOCRC is lower among women than men, the authors called surprising the “the markedly lower likelihood of diagnostic testing” for women, because the population with a diagnosis of IDA had a nearly equal amount of men and women. They explained, “Iron-deficiency anemia is commonly attributed to menorrhagia in premenopausal women, but our study found the disparity in workup persisted even after removal of women with diagnosed cases of menorrhagia or prior hysterectomy. It is plausible that clinicians are more likely to attribute iron deficiency in women to disorders of menstruation. Nevertheless, more research is necessary to uncover why this sex-based disparity in diagnostic follow-up exists and whether substantially lower rates of endoscopic follow-up for women are clinically appropriate.”

Also surprising, according to the study, was that Black veterans with IDA were less likely to receive diagnostic testing than white veterans. “Black veterans of all ages have been shown to have higher CRC incidence and mortality and a more advanced stage of CRC at presentation,” the researchers wrote. “Recent evidence indicates that, despite greater increases in EAOCRC incidence among white adults compared with Black adults over a 15-year period, White adults had higher relative survival. Differences between Black and white adults have been postulated to be associated with differences in risk factor burden, access to health care and follow-up patterns, such as for abnormal results from stool tests performed for CRC screening, as well as structural racism. Our findings of variation in diagnostic testing after IDA and hematochezia diagnosis suggest that there may be specific clinical scenarios amenable to interventions that can reduce disparities in CRC outcomes for Black vs. white adults.”

The study also cited recent evidence showing that EAOCRC incidence is increasing rapidly among Hispanic adults, especially for regional or distant-stage disease, and that Hispanic adults have similar or worse EAOCRC-related survival compared with white adults.29–31 Our study findings indicate that effective strategies for timely diagnostic testing may help address these differences.

The authors concluded that screening rates were low overall and that “optimizing diagnostic test completion among individuals with IDA and/or hematochezia may help improve early detection of EAOCRC and contribute to reducing EAOCRC-related disparities.”

- Demb J, Liu L, Murphy CC, Doubeni CA, Martinez ME, Gupta S. Time to Endoscopy or Colonoscopy Among Adults Younger Than 50 Years With Iron-Deficiency Anemia and/or Hematochezia in the VHA. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2341516. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.41516