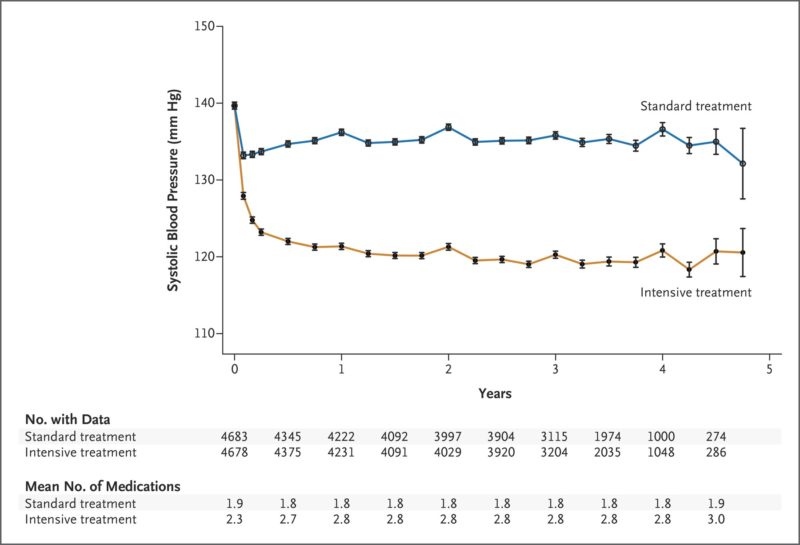

Click To Enlarge: The systolic blood-pressure target in the intensive-treatment group was less than 120 mm Hg, and the target in the standard-treatment group was less than 140 mm Hg. The mean number of medications is the number of blood-pressure medications administered at the exit of each visit. I bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

MINNEAPOLIS — The landmark Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) quickly changed the standard treatment of patients at high cardiovascular risk in the U.S. In light of the significant reduction in risk of death and major adverse cardiovascular events seen in the intervention arm that led to the study’s early termination, clinicians and guideline committees raced to adopt a lower target rate for systolic blood pressure in high-risk patients and embrace the use of intensive therapy to reach the markedly lower goals.1

For the VA, the trial and its results had particular significance. The study included only patients over the age of 50, with an enriched population of participants over the age of 75, in line with the population most commonly treated at the VA. SPRINT included patients with systolic blood pressure between 130 and 180 mm Hg and with at least one other high-risk factor such as clinical or subclinical cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease or a 15% or greater 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease based on the Framingham risk score—all frequent health concerns among veterans. The trial specifically excluded patients with diabetes, which affects one-quarter of veterans, as well as individuals who had prior stroke or polycystic disease.

Consequently, researchers at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System and University of Minnesota had a keen interest in better understanding all the factors that led to the 25% reduction in mortality and major cardiovascular events (first occurrence of myocardial infarction, other acute coronary syndromes, stroke, heart failure or cardiovascular death) seen in the study. SPRINT randomly assigned 9,252 patients to either an intensive arm, with a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg or a standard arm with a target systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg.2

Notably, patients in the intensive treatment arm also received higher doses and more medications designed to lower their blood pressure and “thus were more likely to receive those drug classes shown to reduce clinical events in randomized controlled trials,” wrote the Minneapolis team led by Douglas DeCarolis, PharmD, BCPS, who has since retired. “It is unclear if greater use of these drug classes in the intensive arm may have contributed to these improved outcomes.”

Others have previously questioned the role specific drug classes played in the outcomes seen in SPRINT. One study noted that “less heart failure in the intensive arm was driving the difference” favoring the intensive arm in SPRINT, “suggesting that possible differences in the use of diuretics may have demasked latent heart failure in hypertensive patients with rather high cardiovascular risk.”3

The Minneapolis VA team reanalyzed the SPRINT data to determine whether longer exposure to specific classes of antihypertensive drugs reduced the primary composite outcome after adjustment for study arm, time varying systolic blood pressure achieved, exposure to drug class and specific baseline characteristics. SPRINT left the decision on the antihypertensive regimens to the individual investigators at each of 102 study sites, although a treatment algorithm advised preferred antihypertensive drug classes.

Medications Matter

The VA researchers looked at the impact of thiazide-type diuretics, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers, calcium channel blockers and beta blockers. RAS blockers included angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

They noted that participants in the intensive-treatment arm saw an increase of 68% in use of thiazide-type diuretics, 39% in RAS blockers, 68% increase in calcium channel blockers and 20% in beta blockers during the study. For those in the standard-treatment arm, the frequency of drug class use remained consistent throughout the study period.

The analysis demonstrated exposure of one year or more to thiazide-type diuretics or RAS blockers was associated with approximately 23% fewer primary outcome events compared to less than a year of exposure. In contrast, length of exposure to calcium channel blockers had no significant impact, and exposure to beta blockers for more than one year was associated with a 35% increase in risk of primary outcomes compared to less than one year.

Longer exposure to thiazide-type diuretics and RAS blockers were also associated with 40% and 42% reduction in risk of cardiovascular death, respectively. More than a year of thiazide-type diuretics reduced the risk of heart failure by 47%, while RAS blockers reduced the risk of myocardial infarction by 36%.

“Previous guidelines and expert opinions have suggested the degree of blood pressure lowering is most important in reducing cardiovascular outcomes when treating hypertension,” said DeCarolis and his colleagues. This analysis “suggests the choice of antihypertensive drug classes may also play a prominent role. After accounting for blood pressure reduction and randomization arm, longer exposure to thiazide-type diuretics and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors reduced major adverse cardiovascular outcomes while longer beta-blocker exposure increased these outcome events.

- SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, Snyder JK, et. al.. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373(22):2103-16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. Epub 2015 Nov 9. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2017 Dec 21;377(25):2506. PMID: 26551272; PMCID: PMC4689591.

- DeCarolis DD, Gravely A, Olney CM, Ishani A. Impact of Antihypertensive Drug Class on Outcomes in the SPRINT. Hypertension. 2022 Mar 9:HYPERTENSIONAHA12118369. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18369. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35259925.

- Kjeldsen SE, Narkiewicz K, Hedner T, Mancia G. The SPRINT study: Outcome may be driven by difference in diuretic treatment demasking heart failure and study design may support systolic blood pressure target below 140 mmHg rather than below 120 mmHg. Blood Press. 2016;25(2):63-6. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2015.1130775. Epub 2016 Jan 8. PMID: 26743157.