BETHESDA, MD — Vagus nerve stimulation therapy is a safe treatment option for drug-resistant epilepsy over long-term follow-up, but the treatment does have risks, according to a recent study.

The study published in Cureus evaluated the complications and mortality associated with vagus nerve stimulation, an alternative treatment option for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who aren’t good candidates for surgical resection, over a 23-year period. The study authors are affiliated with Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, both in Bethesda, MD.1

Vagus nerve stimulation, “approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy in 1997 and extended to children ages 4 and older in 2017, is the most cost-effective and frequently used neuromodulation,” according to the report. “This treatment has helped about 45% to 65% of patients achieve at least 50% reduction in seizure frequency. Vagus nerve stimulation includes a pulse generator implanted in the chest that is connected to a bipolar lead that wraps around the left vagus nerve within the carotid sheath.”

“Benefits of vagus nerve stimulation, a lifelong treatment for many patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, include a better tolerability profile than many anti-seizure medications,” the study authors wrote.

In this study, the researchers reviewed the medical records of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy who were treated with vagus nerve stimulation at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center from Jan. 1, 2000, to Dec. 31, 2023. All surgeries, including primary generator implantation, pulse generator replacement, revision and lead replacement, were performed by neurosurgeons or otolaryngologists of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. The mean follow-up time was 10.6 years, ranging from three months to 22 years. The study included both early and late complications related to vagus nerve stimulation therapy over the 23-year period, according to study authors.

“Our study re-demonstrated findings that vagal nerve stimulation is generally safe, though can have some longer term complications to include sleep apnea and sleep disordered breathing,” David Horvat, MD, assistant professor of neurology at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, told U.S. Medicine. “This is a procedure performed both in the military health system and the civilian, and we wanted to see how our outcomes compare to the civilian sector.”

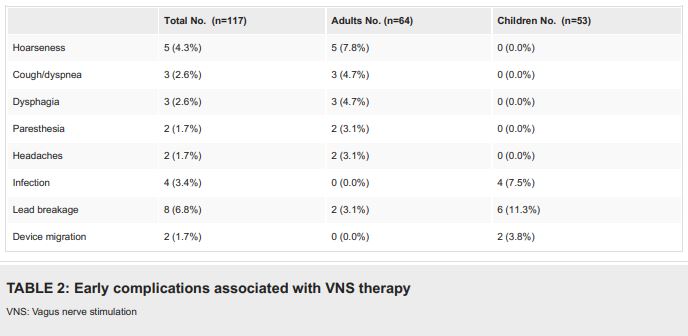

In adults, “the most common complications of vagus nerve stimulation therapy are minor and transient. Children are prone to postsurgical infection, lead breakage and generator migration, which require surgical revision,” the analysis found.

The authors concluded that “late-onset cardiac complications and obstructive sleep apnea can develop in some patients during vagus nerve stimulation therapy and shouldn’t be overlooked. For instance, atrioventricular block can be seen years after vagus nerve stimulation implantation. Urgent EKG monitoring is recommended for patients who develop new syncope or pre-syncope events. In the study, three patients were diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea after starting vagus nerve stimulation therapy, which was set at high intensity for all three patients. It appears the occurrence of obstructive sleep apnea is dose-dependent.”

Study authors also suggested “the risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) may decrease with vagus nerve stimulation therapy over time.”

Potential Option

Horvat recommended that vagus nerve stimulation “should be considered a potential option for epilepsy management in patients who are not candidates for surgical resection.”

“However, this decision and evaluation should be made by an epileptologist who can determine the right treatment option for the patient,” he added. “Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy should be referred and managed by epileptologists who can evaluate for non-medication options to include resection, palliative surgery (to include vagus nerve stimulation), or ketogenic diet. Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy benefit from early referral to an epileptologist.”

This study included 55 patients that had 117 vagus nerve stimulation procedures performed from 2000 to 2023. Fifty-three procedures (45.3%) were performed on children. Forty-three adults (78.2% of participants), mean age of 37.0, and 12 children (21.8%), mean age of 12.8, had vagus nerve stimulation implantation. The mean age at primary implantation was 26.6 years for adults and 8.7 years for children, the authors pointed out.

The duration of epilepsy at the time of primary implantation was 13.0 years for adults and 6.1 years for children, while the duration of vagus nerve stimulation therapy averaged 10.6 years, ranging from three months to 22 years. “Of the patients, 22 (40%) had lesional epilepsy, and four patients (7.3%) were diagnosed with genetic generalized epilepsy”, according to the report.

Patients underwent the following procedures:

- primary implantation of the vagus nerve stimulation system (n = 55),

- replacement of the vagus nerve stimulation pulse generator (n = 46),

- replacement of the leads (n = 2),

- incomplete vagus nerve stimulation removal surgery (n = 6) or

- any other vagus nerve stimulation related surgery (n=8).

Vagus nerve stimulation surgery-related complications were reported in 24.8% of all procedures. “Four patients (7.3%) suffered from late complications from chronic stimulation,” according to the authors.

The study determined that “almost all transient complications were reported by adult patients. Most of the pediatric patients, in which infection, device migration and 75% of the lead breakage cases were seen, suffered from epileptic encephalopathy with intellectual disability and behavioral changes which may contribute to abnormal manipulation of the device. The results are consistent with previous studies that showed intellectual disability is a risk factor for infection and device malfunction.”

Over the 23-year study period, four patients died. The authors explained that one patient died from a generalized tonic-clonic seizure that led to a fall which resulted in a large subdural hemorrhage, while two patients died from probable SUDEP—one within a year after vagus nerve stimulation implantation and one 3.7 years later. No SUDEP was reported by patients who had vagus nerve stimulation therapy for longer than four years, the researchers noted. The incidence of SUDEP was found to be 3.4 per 1,000 person-years.

The final patient died from medical complications. “All had recent vagus nerve stimulation interrogation and were without signs of device malfunction,” the authors wrote.

A major strength of the study is “the long-term follow-up of patients with vagus nerve stimulation therapy, with the longest follow-up time being 22 years. Limitations of the study include its retrospective design and relatively small sample size. Also, data were missing due to the transition of the medical record system,” the study authors noted.

The researchers recommended that “further studies are needed to clarify the relationship between vagus nerve stimulation and obstructive sleep apnea. Also, although it’s considered a palliative care procedure, vagus nerve stimulation therapy should be offered to patients who are not candidates for surgical resection.”

- Ma Y, Lehman N, Crutcher R, Young W, Horvat D. Complications and Mortality Rate of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Cureus. 2024 Jul 4;16(7):e63842. doi: 10.7759/cureus.63842. PMID: 39099993; PMCID: PMC11297726.